ATLANTA (AP) — Libertarian Chase Oliver isn’t going to win Georgia’s Senate race.

But the 37-year-old self-described former Democrat could command outsize national attention, influencing the election night outcome and potential next round in a highly competitive contest expected to help determine whether Democrats or Republicans control the Senate over the final two years of President Joe Biden’s term.

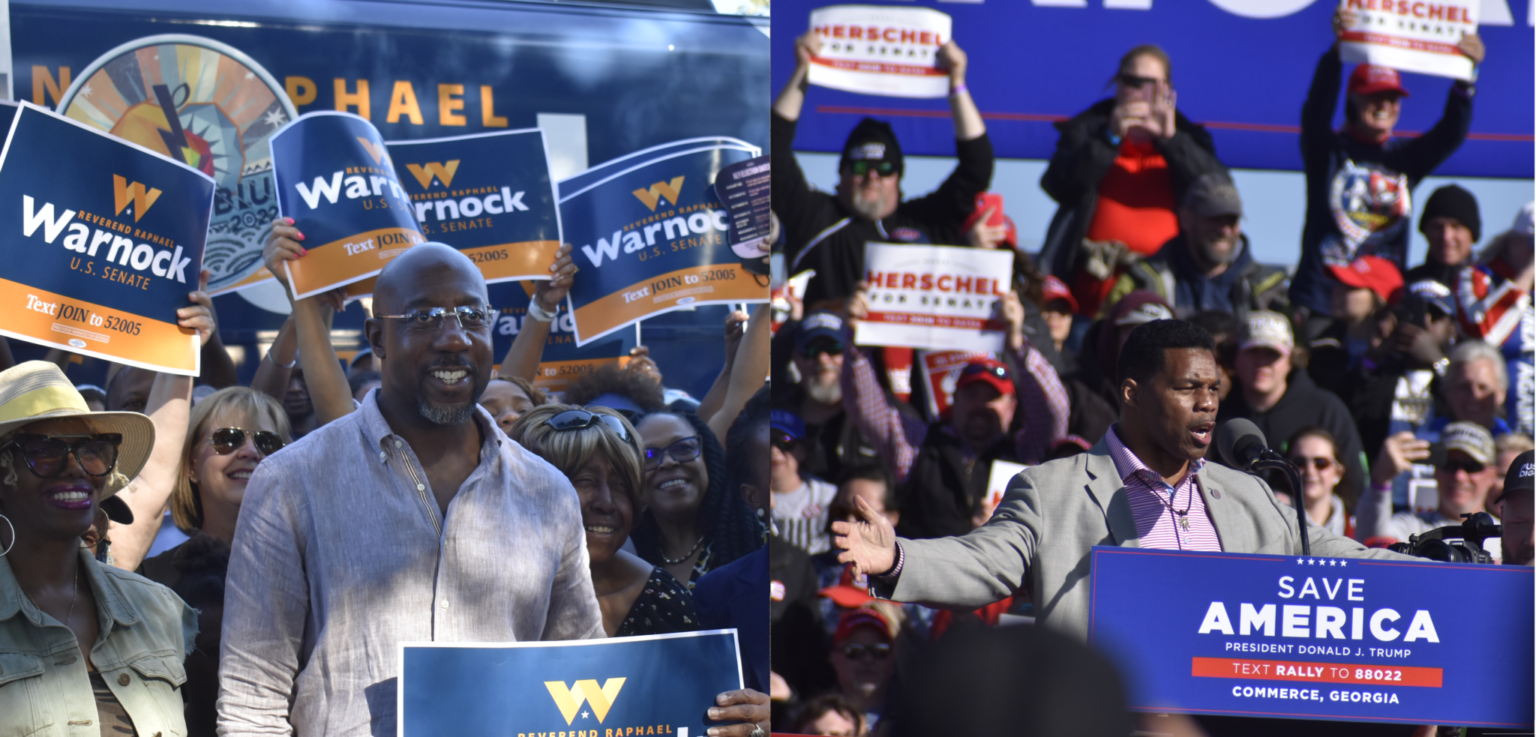

Oliver is the third name on the ballot in the marquee matchup between Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock and Republican Herschel Walker.

In most states, that make would Oliver an afterthought. But Georgia law requires an outright majority to win statewide office. With polls suggesting a tight contest between Warnock and Walker, it may not take a considerable share of the vote for Oliver to force a runoff. It’s a scenario that played out in Georgia’s two Senate races in 2020, both won by Democrats, giving their party the slimmest of Senate majorities — 50-50, with Vice President Kamala Harris the tiebreaking vote.

The chance of an encore could be growing if Oliver’s level of support increases as Walker struggles to navigate his rocky past, including reports that the staunch anti-abortion Republican paid for the 2009 abortion of a then-girlfriend who later gave birth to their child.

“I do think that there are a lot of Republicans who feel like he’s not able to really be the best person to espouse the policies of limited government and keeping spending under control and lowering taxes,” Oliver said.

Oliver was getting a shot at the spotlight in a debate scheduled for Sunday night with Warnock, senior pastor at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta who won his seat via special election in 2021 and now seeks a full six-year term. First-time candidate Walker, who made his name in college and professional football, did not accept an invitation to the Atlanta Press Club forum. Under the club’s rules, he will be represented by an empty podium.

Walker and Warnock met in their lone one-on-one debate Friday in Savannah. Oliver was not included because he did not meet organizers’ polling threshold.

A runoff, if needed, would take place Dec. 6, setting up a four-week blitz after the general election, Nov. 8. That’s half the time of Georgia’s runoff campaign two years ago when Warnock and now-Sen. Jon Ossoff prevailed over their Republican rivals with Senate control at stake.

Neither the Warnock nor Walker campaigns will publicly discuss a possible second round.

“We’re focused on getting the job done Nov. 8,” Walker spokesman Will Kiley said.

Whether a Georgia runoff could again decide the Senate majority will depend on the outcomes of competitive races in Arizona, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Nevada and elsewhere.

Oliver wants to use the attention to raise awareness that Libertarians offer a third choice to voters across the spectrum, whether limited-government conservatives or social liberals who support abortion and LGBTQ rights. He noted that he was once an anti-war Democrat but gravitated to Libertarians when he became disillusioned that President Barack Obama did not curtail U.S. military interventions.

Since 2014, Libertarians in Georgia have won 2% of the vote, on average, in contests for governor and U.S. senator.

Even if Walker gives Oliver his best opening to increase that share, it’s not necessarily true that Oliver’s candidacy would help Warnock in the long run.

In November 2020, Libertarian Senate candidate Shane Hazel won 2.3% of the vote in a race where Ossoff was challenging Republican incumbent David Perdue. Perdue led Ossoff in the general election by about 88,000 votes, but finished with 49.7% of the nearly 5 million votes, mere thousands from a majority that would have meant a second term and a continued GOP majority in the Senate.

With a second chance, Ossoff outpolled Perdue by about 55,000 votes and won a full term.

Warnock won his seat over then-Sen. Kelly Loeffler, a Republican, the same night as Ossoff. But Loeffler and Warnock had advanced to a runoff from a 20-candidate special election field that featured candidates of all parties, so neither of them had come close to an outright majority in the first round.

If Oliver forces a runoff this time, he said, “It means that there were enough voters who felt like they weren’t being listened to. And I hope that whoever eventually wins the race, maybe listens to those voices in the future and realizes they have to represent all of Georgia and not just a partisan interest.”