Mark of the Potter has been a staple in Habersham County for over fifty years. That doesn’t mean, however, that it hasn’t evolved over the years. With Chad Peck now at the helm, the changes have been perfectly designed to bring the pottery shop into its next season.

Chad Peck inherited the shop from his step-father Jay Bucek. Bucek, a trained potter in his own right, saw an opportunity to meld his passion for pottery with his love of the Northeast Georgia mountains. Bucek bought the Mark of the Potter in 1983 when pottery was already the focus of the facility. The historical significance of the place goes back much further than the Bucek-Peck ownerships.

Water-powered mills on the site

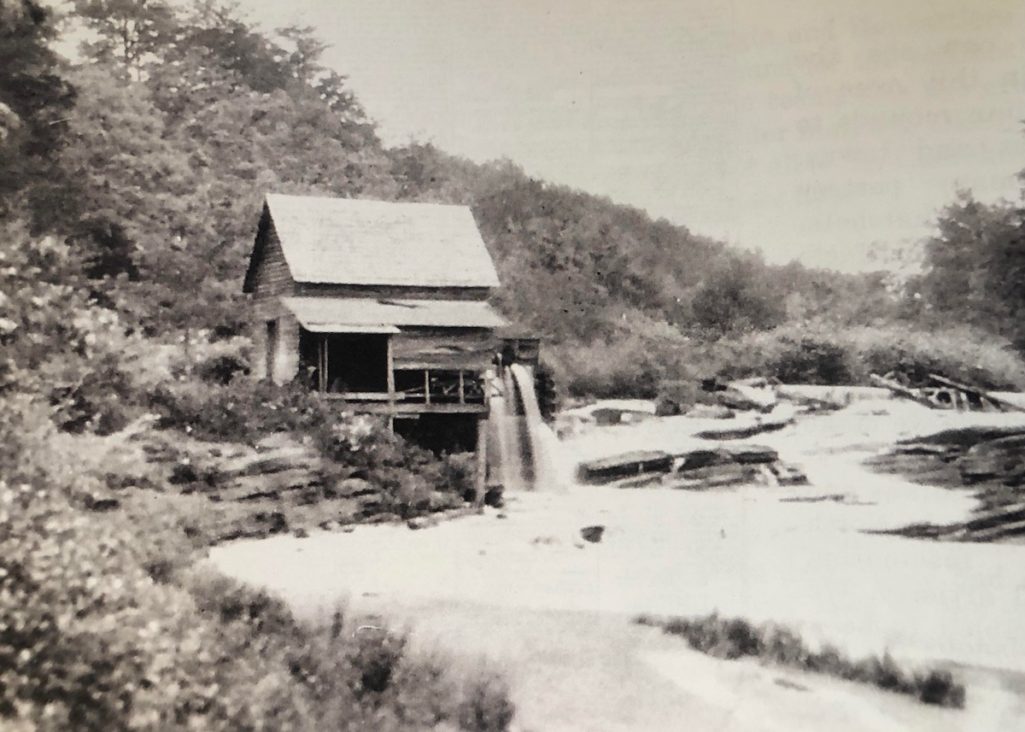

Several water-powered mills were built on the site where Mark of the Potter now sits. The first of these was a grist mill built in the 1800s.

Hill’s Mill

During the 1820s and 30s, both Clarkesville and Batesville were thriving. Both had shops, churches, schools, and water-powered mills along the Soque River. According to the latest history of the place, Mark of the Potter: From Corn to Clay, those mills included sawmills, cotton carding mills, and grist mills, which were located along the river in places that could be “dammed up and channeled through a ‘raceway’ or ‘millrace.'” The process created the power that ran the mills.

The first mill on the site of today’s Mark of the Potter was Hill’s Mill, in which an outside water wheel turned to create the power inside the mill. The mill was built in 1821, and the original foundation of Hill’s Mill can still be seen today under one of the outbuildings. Brothers Daniel and Isaac Hill had other mills in the area as well. One was a sawmill that produced the lumber used in building the Grace Episcopal Church in Clarkesville. Hill’s Grist Mill was in operation until the mid-1920s, long after the Hill brothers had passed away.

Grandpa Watts Water Ground Meal

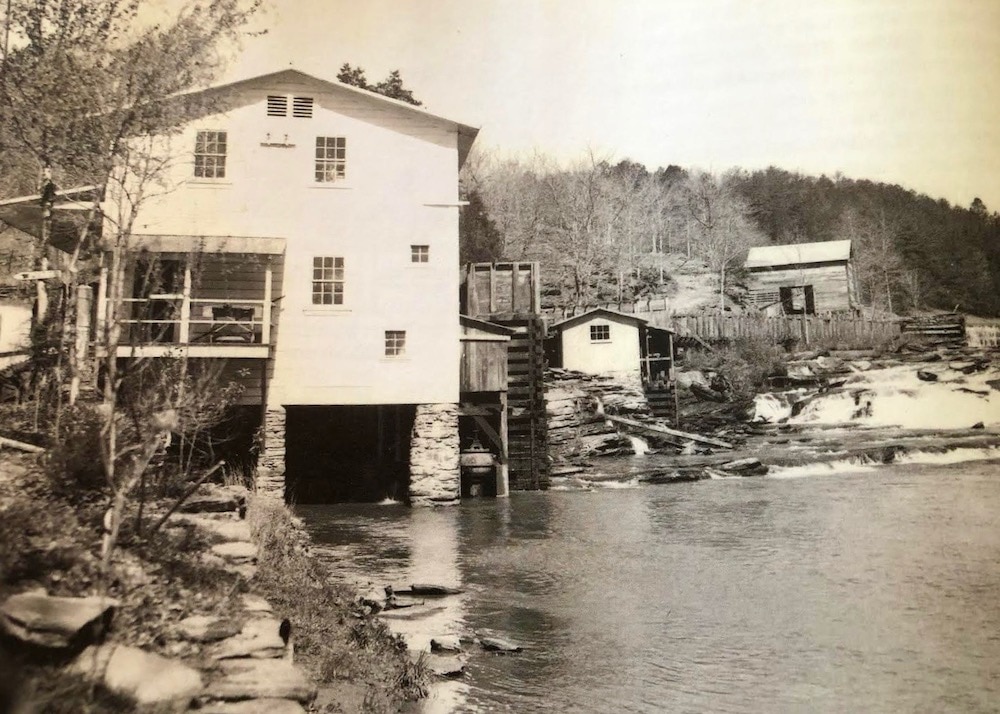

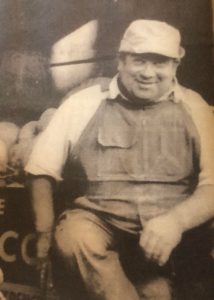

Although Batesville continued to grow in the early 1900s, the Hill’s Mill sat empty and needed repair. In 1928, Robert Watts and his father, Allen “Grandpa” Watts, bought the mill and its surrounding property. Robert and his father repaired the mill and had it opened within a month. The sign announcing Grandpa Watts Water Ground Meal still graces the front of the Mark of the Potter building.

Robert and Letie later built a brick home across the road and a grocery store/gas station next to it. There was also a grade 1-7 school there that operated from 1900-1935. The area was busy with traffic from visitors and neighbors, but the Hill’s Mill sat empty and in need of repair. Although they reclaimed the mill during the Depression, the updated grist mill was able to turn a profit.

Grinding corn for moonshine

The Watts also discovered another way to make money–grinding corn for moonshine. During Prohibition, Highway 197 became known as the Moonshine Highway. In an interview given in 2016, former Mark of the Potter manager Michael Foust related, “Folks used to say that sugar [necessary for making moonshine] came up the road, and liquid corn went down the road.” In fact, the moonshiners knew the curves of the highway so well that they drove it without headlights and by the light of the moon whenever possible so revenuers could not catch them.

When the Watts built a new mill on the same site, they put a large open area onto the top floor. At first, the area was used for community dances and gatherings. However, as the need for ground corn grew, the upstairs was turned into a storage area for the bags of corn kernels waiting to be ground. Some of the bags of kernels were watered over time to create the corn mash needed in the process. Although there’s no evidence that the Watts ever made moonshine themselves, later owners of the building found glass jars that smelled faintly of moonshine on all three levels of the mill.

Interestingly, the huge trout who still reside just below the mill were drawn to that part of the Soque for two reasons. First, the river has deep, cool pools there for the fish to spawn in. Second, and possibly more important, grain constantly fell through the floorboards and into the water. Letie Watts took on the task of supplementing the grain dropped through the floorboards with fish food. The trout who reside there are still giant and are protected from fishing.

The mill fell into disrepair after a major flood in the 1960s. Floodwaters washed out part of the dam and the raceway. The rising water also ruined the machinery within the mill. The mill was abandoned afterward because the costs of repairing it were too high.

From cornmeal to marked pottery

John and Glen LaRowe had taken up pottery as a hobby in Atlanta and dreamed of a time when they could retire to Northeast Georgia and pursue their passion full-time. They began looking for a place in North Georgia in 1957 and even built a home on Lake Burton. However, in 1968, John and Glen purchased the old mill, investing in their dream of pursuing pottery during retirement.

John began by renovating the large area on the third floor and creating a living space there. By 1969, the LaRowes moved into the upstairs floor on weekends as they continued to work on the main floor of the property. They left the grist mill machinery in place and decorated the walls with old tools. Once the work was completed, the LaRowe’s set up a pottery studio on the main floor.

Mark of the Potter opened later that same year. The name of the shop was chosen to identify the kinds of potters and pottery that could be found within it. Only the best potters at the time sighed the bottom of their pieces or used a designated seal for their work.

The timing of opening the store was perfect. It happened at the same time visitors were flooding the area to see what had been done in the new Alpine town of Helen. And John was quick to see the importance of publicizing the North Georgia area to potential visitors. John was also the first president of the Georgia Mountains Travel Association. He came up with the idea of creating a specialty cookbook that would draw interest to the area. The cookbook, Somethin’s Cookin’ in the Mountains, was first printed with ten thousand paperback copies and later reprinted with ten thousand hardback copies. The book is now out of print, but its impact on tourism to the area was significant.

In 1985, the LaRowes were ready to travel some and explore the next phase of their retirement. They sold the mill to Jay Bucek, a potter who had been supplying them with his work for three years.

Mark of the Potter’s second owner

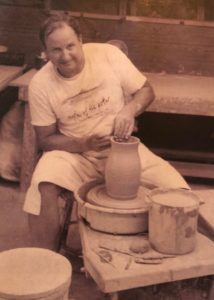

Jay Bucek was a teacher at Agnes Scott College and ran his own pottery business, traveling to art shows and events to market his pottery. He had been supplying his pottery to Mark of the Potter when he heard the LaRowes were ready to move on. He jumped at the opportunity to purchase the Mark of the Potter. In 1985, Jay and his wife Cathy, also a potter, moved into the brick house across the street and took over the business.

Jay wanted to protect the heritage and history of the mill while he made some updates and changes. His first update was to build a new kiln in the building that had one time been the grocery across the road. Two years later, major reconstruction work had to be done on the mill to replace the foundation and replace the deteriorating beams. The mill was actually lifted six inches above the foundation with twenty-ton jacks for the work to be completed.

Mark of the Potter today

Chad and Mayte Peck became owners of the Mark of the Potter in 2019, just in time to plan its 50th anniversary celebration. As a contractor, Chad has enjoyed upgrading the electrical work and finishing off parts of the mill that had been left unfinished.

Chad has also brought new ideas to Mark of the Potter. He brought a Cone 10 Kiln in from North Carolina, carefully moving it piece by piece and rebuilding it in the building across the road. Mark of the Potter now has two kilns capable of heating to a temperature of 2350 degrees with propane, creating brighter colors in the process. All of the potters now use a special mixture of clay, mixed solely for the Mark of the Potter, from Highwater Clays in Asheville, North Carolina.

Chad also worked to create a more fluid environment in which to show off the pottery. He has carefully cleaned up the area to show the grist mill mechanics that are all still in place.

Mark of the Potter continues to be a special place in Habersham County. Chad has added picnic tables along the river for visitors to use as they travel. And he and Mayte continue to support the trout. The fish food machine on the back porch which distributed the food for quarters is no longer in operation, but bags of fish food can be bought for a dollar at the register.

One extra thing to enjoy is Chad’s personal tour of the mill works. If he’s in the shop, he can explain the entire operation both in the basement and the main floor. In all the years I’ve been visiting Mark of the Potter, I had missed most of the mechanical works in the shop. The works can now be easily seen, and hearing about the process of water-powered mills is fascinating.

Chad, Mayte, their daughter Victoria, and their dog Biscuit are totally invested in continuing the legacy of the Mark of the Potter and the old Watts Mill. As the history of Mark of the Potter concludes: “Mark of the Potter: Like the river, ever-changing, ever the same!”