By: Madeline Laguaite | Georgia Health News

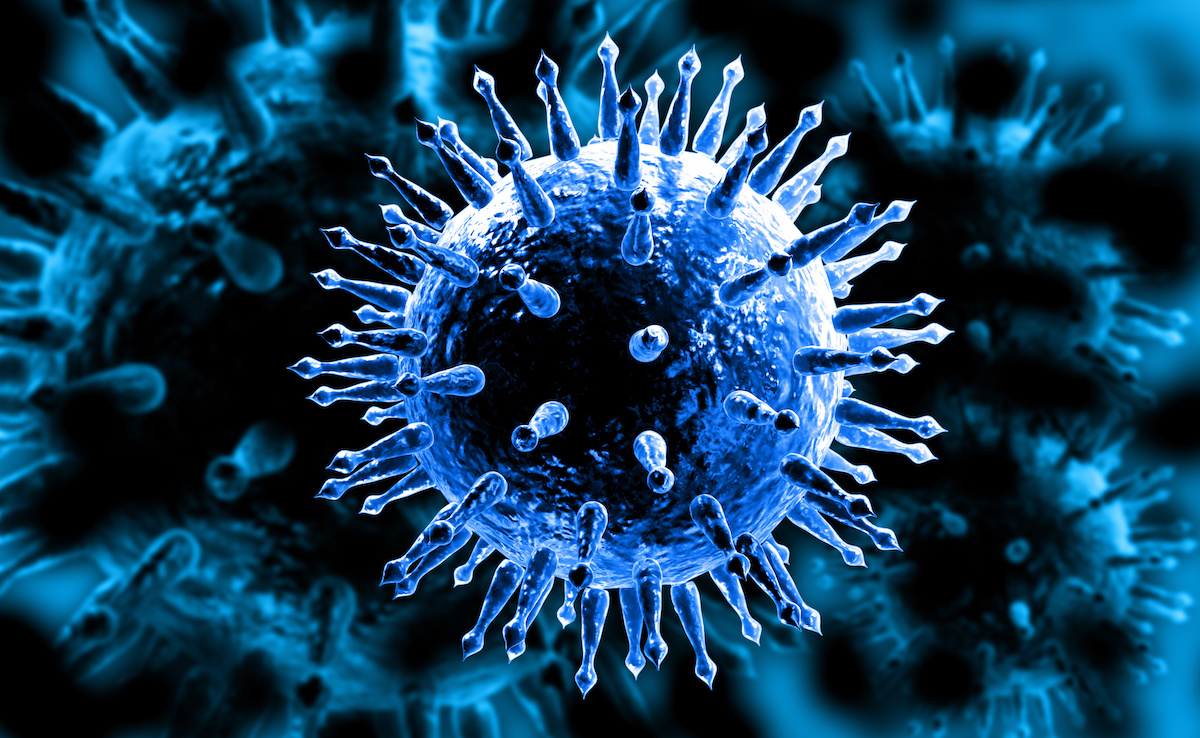

University of Georgia researchers are receiving millions of federal dollars to help create a “universal” flu vaccine. But what does that term mean? And will a breakthrough vaccine persuade more Americans to get flu shots?

Right now, fewer than 40 percent of adults get a flu shot. And that’s bad.

During the 2017-18 flu season, at least 145 people in Georgia died from influenza. (A few deaths may not have been recorded as flu-related.) During that period, the flu vaccination coverage estimates among all adult age groups were lower than in the previous seven flu seasons, the CDC reported.

The National Institutes of Health recently signed a contract with the University of Georgia for funding to develop a universal flu shot. Led by Ted Ross, Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar of Infectious Diseases and director of UGA’s Center for Vaccines and Immunology, the project aims to create a vaccine to protect against many strains of influenza virus.

The NIH will offer $8 million in the first year and up to $130 million over the next seven years, Ross says.

He says he believes a broader vaccine could affect the flu-shot statistics “because the same vaccine can be given at any time and move multiple years without reformulation.” The Ross project is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

“The goal of our NIAID contract is to develop broadly reactive influenza vaccines to elicit protective immunity against all versions of influenza,” Ross says.

Glen Nowak, a UGA professor and director of the Center for Health & Risk Communication, has done research concerning pandemic influenza vaccines and the communication challenges that come with them.

The term “universal” that’s used often to describe Ross’s upcoming flu vaccine may be misleading, Nowak says.

The actual definition, according to NIH, is fourfold. To be considered “universal,” the vaccine must be “at least 75 percent effective, protect against group I and II influenza A viruses, have durable protection that lasts at least a year and be suitable for all age groups.”

When most scientists have talked to journalists and others about the universal vaccine, Nowak says, “They’ve portrayed it as much more than that. The word ‘universal’ is problematic because it does create the impression that all of us might just have to get one flu shot and we’ll be done for life, and I don’t think that’ll actually ever be the case.”

But, like Ross, Nowak thinks an improved vaccine could improve flu shot coverage statistics.

“Would it help get more people vaccinated? I think so,” Nowak says. “If you look at any age group, we’re sort of we reached a plateau. What will it take to get us to go to a higher plateau? I think it will be in improvement in the vaccine.”

Nowak says it’s possible that people will need two doses every season since the NIH “universal” vaccine definition doesn’t include B strains.

“It could be better against one type but it doesn’t address the other type, which would mean that we now would be in, in most people’s perspective, a worse position,” Nowak says. “It has the potential to actually create more rather than less confusion and more complexity rather than less complexity in the short term.”

Nowak says with most vaccines — when scientists think they have a strong, viable candidate vaccine — it takes about 10 years from that point to get licensed and ready for use.

“I think there’s people that think that if Ted discovered something tomorrow, we’re two or three years away,” Nowak says. “We’re a decade, probably a couple of billion dollars away, because clinical trials are expensive.”

When asked when he thinks the vaccine could potentially hit markets, Ross says it “could be as soon as seven years and as long as 20 years.”

Why don’t people get vaccinated?

People’s interest in getting a flu shot is highly correlated with their age, Nowak says, and CDC data support this. Older people are usually aware of the danger of flu, and health care officials make a point of urging seniors to get the shot. But many younger people view influenza as a manageable illness, Nowak says.

Ross says most young adults don’t see influenza as a serious infection, but more like having a cold.

“They may be miserable, but they’ll manage it,” Nowak says. “They’re not familiar with the fact that influenza can cause serious illness, and if it does cause serious illness, oftentimes it can cause hospitalization.”

And if the virus gets into the major organs, “you’re probably going to be in serious trouble,” Nowak says.

Fortunately, that very rarely happens.

Caleb Shelton, a junior environmental engineering major at Kennesaw State University, says he usually gets a flu shot every year.

“I think it’s important because there’s different strands of the flu virus every year,” Shelton says. “It can help you from getting sick in the future from that strain of virus.”

Health professionals face a challenge in convincing younger generations of the importance of the flu shot.

“Effectiveness is not as high as we’d like it to be and it’s not as high as recommended childhood vaccines,” Nowak says. “For some people, that’s a negative because they want it to be much more effective and their sense is that if it’s not at 80 percent to 90 percent effective, it’s not worth it.”

Payne Inman, a senior civil engineering major at Kennesaw State, doesn’t get flu shots.

“I’ve done some reading and one of the things that I found out was that it’s only about 35 percent effective,” Inman says. “I don’t know if that’s true or not but I read it a few years ago. That’s why I don’t get it because I feel like it’s not very effective either way.”

It’s true that no flu vaccine is 100 percent effective. Flu viruses vary each year and even change within a season. Vaccines have to be reformulated each year, and the decisions on formulation have to be made six months early to allow for production. So the vaccine used in a particular flu season may turn out to be less effective than planned.

But limited effectiveness of vaccines is not a sound reason to skip the flu shot, Nowak says. “There’s nothing else that can provide you any protection,” he says. “So even protected at 10 percent, 20 percent, that’s better than anything else can offer.”

And public health officials point out that when vaccines reduce the level of influenza in a population, they can reduce the ability of the disease to spread within that population. To put it in personal terms, if a shot keeps you from getting the flu, you won’t spread the disease to someone else.

There’s a myth that only unhealthy people get the flu. While individuals who are older or have chronic health conditions are more likely to contract influenza, according to the CDC, severe flu can strike suddenly and unexpectedly.

“Every year there are young people, young adults who are perfectly fine and three days later, they’re dead,” Nowak says.

Many people also believe they can contract influenza from a flu shot, according to the CDC. But as Nowak says, that’s a misconception and “it’s essentially not true.”

The reason for this is that flu vaccines use an inactivated flu virus. So in other words, the virus is dead.

Flu mist — which is used sparingly in the United States — uses a weakened virus. Theoretically, it could cause someone to get the flu, although Nowak says this is rare.

There are various reasons why some people may still believe flu vaccines cause flu, Nowak says. One major reason is that some people don’t feel well after getting the shot. It’s not uncommon to have a low-grade fever, headache or muscle aches seven to 10 days after getting the vaccine, the CDC says.

However, these unpleasant side effects can actually be a sign that the vaccine is working, Nowak says.

“That’s what the immune response looks like: low-grade fever, lethargy, you’re not going to have as much energy,” Nowak says. “That’s a good thing. But we haven’t really done a good job of letting people know that’s a good thing.”

Health care professionals sometimes don’t make clear to people that the flu shot doesn’t give instant protection. The vaccine needs time to prepare your body to ward off the infection. Once you get a flu shot, you’ll still be vulnerable to catching the flu during the following two weeks, Nowak says.

“Oftentimes what’s happened is people wait until flu has arrived in their community and then they go get a flu shot,” Nowak says. But by then they may already be about to come down with the flu. “Their expectation is that the vaccine will be immediately effective, so that’s easy to attribute your flu to the vaccine if that happens.”

The Thanks Mom & Dad Fund supports GHN’s reporting on aging issues