This unusual school year for Georgia students can be a time to restructure public schools in the state to be less data-driven in the future, said Superintendent Richard Woods.

“There is a ‘normal’ we should not and cannot go back to – a ‘normal’ of data points determining destiny, scores oversimplifying a student’s worth, and blame and shame serving as the drivers of education reform,” Woods said. “It’s my hope that our collective efforts to choose compassion over compliance during this pandemic have underscored for all of us what is truly important.”

Woods released a plan Monday afternoon outlining his aspirations for the future of Georgia public schools.

The plan calls for reductions in high-stakes testing such as Georgia Milestones, long a target of criticism from the superintendent.

Woods calls for lobbying the federal government to lower the number of tests it requires to less than a dozen and adopt a system in which students would only be tested in third, fifth, and eighth grades and once in high school.

Woods’ plan also calls for reworking the accountability systems that measure teachers’ and schools’ performances and to make teaching a “profession that is elevated, not demonized.”

Woods escalated his campaign against high-stakes testing during the pandemic, as school closures made it difficult for teachers to prepare their classes for the tests, which can factor into teacher accountability scores and make up a large portion of some students’ final grades.

Georgia was one of the first states to apply for and receive a high-stakes testing waiver last spring after Gov. Brian Kemp ordered school buildings shut to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

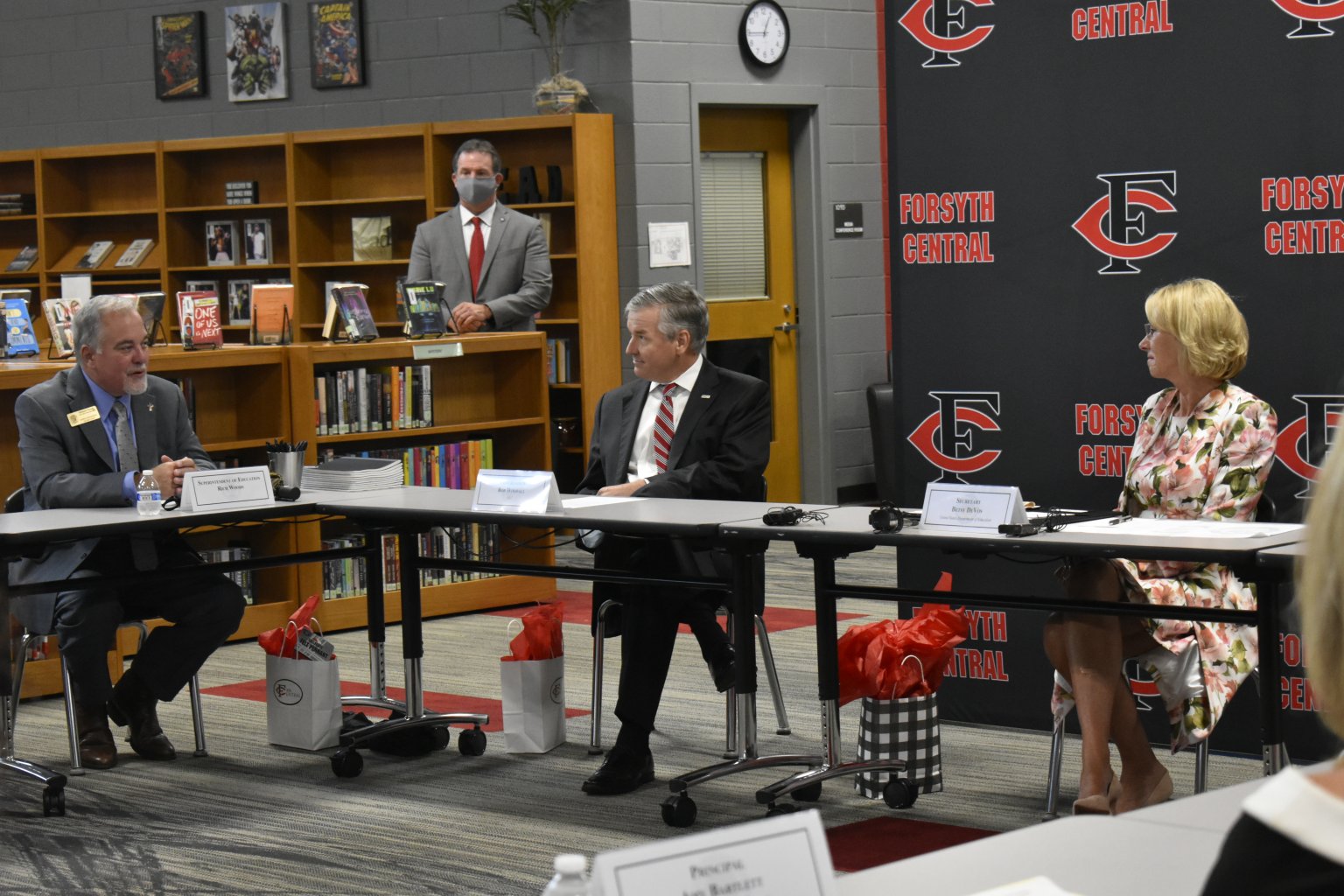

Officials were banking on another waiver this year as some of the state’s districts with highest enrollments continue learning partially or entirely online, but U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos announced last month she would not be granting waivers to states again. She also pressed for students to return to the classroom.

Woods proposed lowering the stakes of the tests by decreasing the amount of a student’s final grade they can comprise from 20% to .01%, but the state school board rejected that idea, instead agreeing to lower the tests’ weight to 10%.

The board is set to take a final vote on the change next month after a period of online public comment.

Woods’ plan also calls for increasing access to a well-rounded education, including STEM classes, fine arts, computer science, and foreign language and creating multiple diploma pathways for students who wish to go from high school into college, a trade, or the military.

“To be clear, this is not a shift in direction – it is an opportunity to build on what has already been accomplished,” Woods said. “Over the last several years, my team has worked with local school districts, policymakers, and educators on the ground to get state testing requirements in line with the federal minimum, incorporate indicators in the accountability system that go beyond the test, reduce the outsized impact of assessments on teacher evaluations, and re-center educational efforts around the whole child.”

“What we cannot do is check these items off our list and consider our job done,” he added. “There is work still to do, and our students deserve nothing less than our full efforts.”

This article appears in partnership with Georgia Recorder