Georgia lawmakers passed a hate crimes bill Tuesday with bipartisan support, pushed to action by a viral video of the February killing of an unarmed Black jogger in Glynn County.

Gov. Brian Kemp commended legislators for passing the landmark House Bill 426 and his office indicated he will sign it if it passes legal review. Georgia is one of just four states without a hate crimes law. The new law would add penalties for crimes committed when motivated by race, religion, sexual orientation, gender or disability.

The Senate voted to pass the bill 47-6 and the House followed with a 127-38 approval.

House Speaker David Ralston, who pressed the Senate committee to advance the bill it had bottled up for more than a year, called the legislation’s passage “a defining moment for Georgia.”

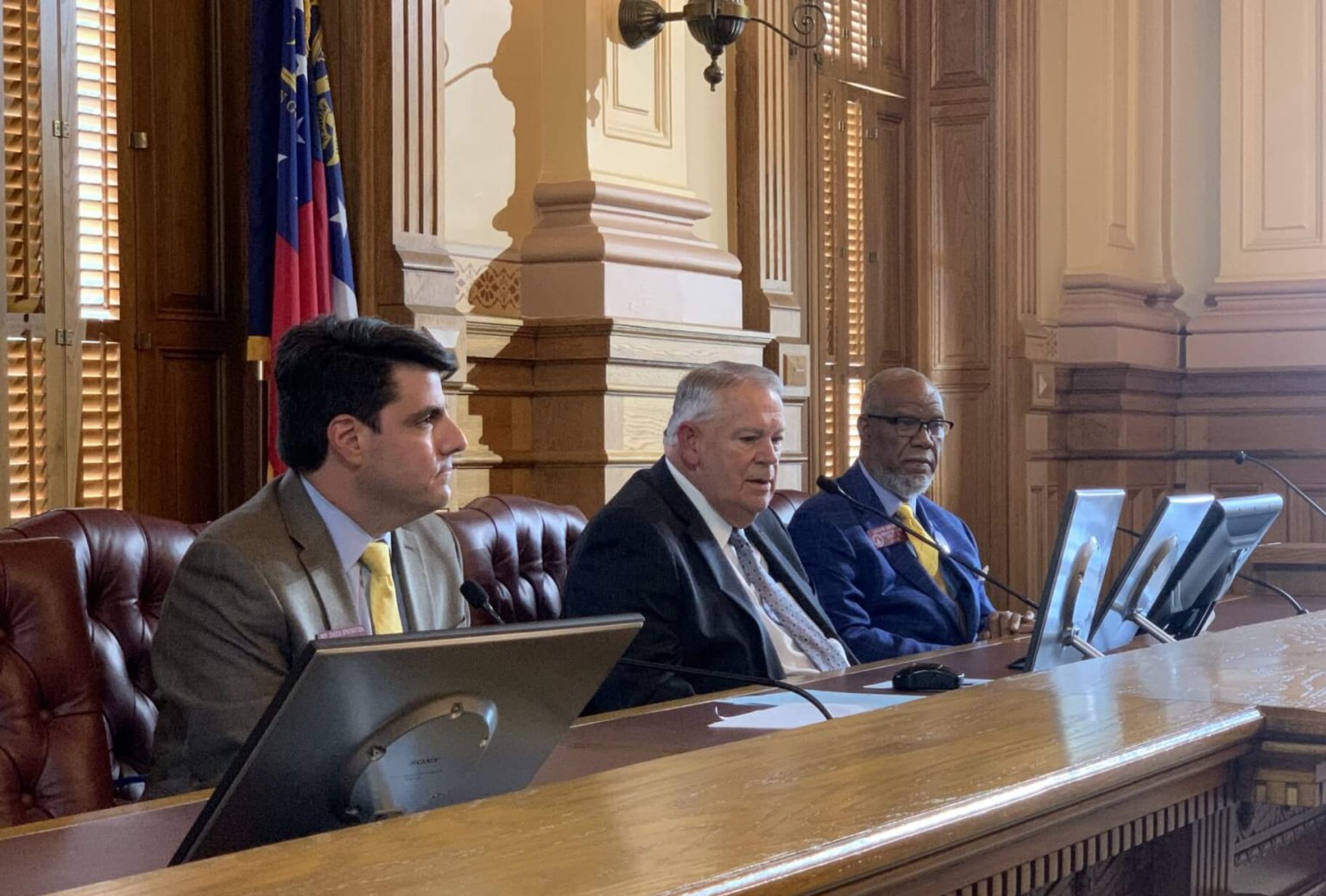

The Blue Ridge Republican said after the vote that he was disturbed when a Senate committee Friday added police and other first responders as a protected class because it threatened the bill’s broad, bipartisan support. The bill was co-sponsored in his chamber by Dacula Republican Rep. Chuck Efstration and Columbus Democrat Rep. Calvin Smyre.

“You don’t pass a hate crimes bill – which is a piece of legislation of this kind of historic nature and consequence – on party lines,” Ralston told reporters. “And some people don’t get that sometimes it’s a good thing to work across party lines.”

Georgia’s 2000 hate crimes law was struck down as too vague by the Georgia Supreme Court four years after it passed. Legislators introduced other hate crimes bills since then but they failed to gain much traction.

Smyre choked up Tuesday putting the hate crimes law in historic context. Smyre was around when lawmakers passed the last hate crimes bill that didn’t survive a court challenge.

“I’ve been here for 46 years and I’ve seen a lot, and I’ve had a lot of moments in my career but today is the finest,” said Smyre, who is the longest-serving member in the House.

More than a few lawmakers say the need to pass hate crimes legislation took on a new urgency after the viral video showing the February shooting death of African American Ahmaud Arbery near Brunswick. Recent courtroom testimony from a state investigator included an account that one of Arbery’s accused killers muttered a racial slur after shooting him.

As recently as Monday, the hate crimes bill appeared to be buried in partisan controversy after Athens Republican Sen. Bill Cowsert added police officers and other first responders to the list of protected groups in a Senate committee hearing late Friday.

Adding first responders drew immediate backlash from some legislators who said it was disrespectful when much of the momentum behind the bill came from the context of violent deaths of Black people, sometimes at the hands of police officers. Efstration said the change with just a few days left in the 2020 legislative session amounted to a “poison pill.”

Over the weekend, Senate Democrats and Republican leaders worked on a plan to move police protection language from the hate crimes bill and insert it into House Bill 838, which allows Cowsert’s protections for police while stripping the hate crimes bill of a provision that appeared to doom its chances.

The hate crimes legislation languished in the Senate Judiciary Committee for more than a year after narrowly passing the House. The Republican-dominated committee suddenly gave it a public hearing Thursday and a day later added the first responders as a protected class.

The committee voted 5-3 along party lines to pass the bill with Cowsert’s change and lawmakers unleashed sometimes fiery rhetoric over the weekend before a Senate committee got together Monday to cement the compromise that lawmakers overwhelmingly supported Tuesday.

Judiciary chairman Jesse Stone, a Waynesboro Republican, said people often asked why he didn’t bring the bill up for vote for 18 months.

“The easy answer is we didn’t have the votes,” he said. “It took the events that are shaking our nation and the leadership of our lieutenant governor to help forge a consensus, particularly among my Republican brethren.”

The amended bill also adds a requirement that law enforcement collect hate crime data closed to the public, a wrinkle from Lt. Gov. Geoff Duncan’s plan. The data collection is designed to help investigators track how often people in the protected classes are targeted.

Georgia Recorder reporter Jill Nolin contributed to this report.

RELATED

Bill to protect police passes, shifts bitter debate from hate crimes effort