This week, To Kill a Mockingbird, the stage play based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning 1960 novel by Harper Lee, is going onstage at Habersham Community Theatre in Clarkesville. The show has garnered such interest that most of the performances for the 12 planned shows—June 4-8 and 11-15—are already sold out as of this writing, and two of those dates were just recently added to accommodate the demand. A few tickets remain.

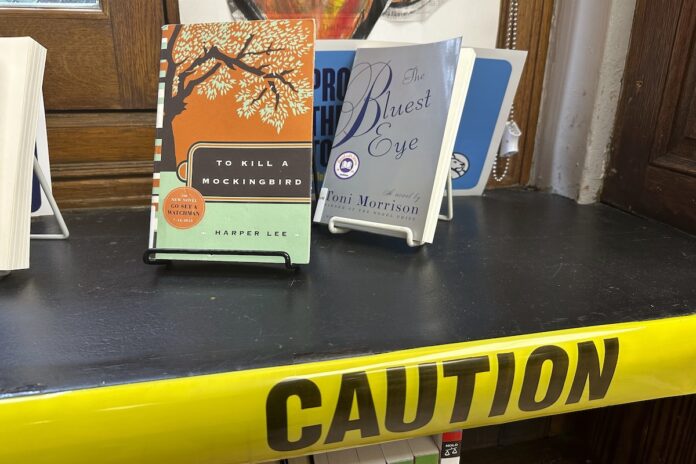

The book and movie (1962, with an Oscar-winning performance by Gregory Peck) are still both regarded as highly controversial, and school boards of all political stripes have tried to ban it over the years—among their objections its 48 uses of the hated “n-word,” and its description of rape and its aftermath.

The story, in all its forms, focuses on an attorney, Atticus Finch, and his two children, Scout and Jem, in the fictional town of Maycomb, Alabama. The climactic scenes involve the trial of young Black man for the rape of a young white woman—an act he did not and could not have committed.

To many readers and playgoers, the appallingly racist behavior and people depicted in the story are relics of the past. Lee’s real hometown of Monroeville, Alabama, is some 350 miles from Habersham County, and the incidents depicted in the novel and play took place some 90 years ago. But our region has its own history of racial cruelty, prejudice, and discrimination, even in more recent times.

Now Habersham researched some of these 20th century events and will recount just a few of them, remaining mindful that our worst racial days are not far behind us.

Let’s start with the real Alabama incident Harper Lee likely had in mind when she wrote her book in 1933.

Scout’s real inspiration

A Black man named Water Lett was accused of rape by a poor white woman named Naomi Lowery in Monroeville. The trial was covered by the Monroeville Journal, of which Lee’s father was the editor. As in the rape trial in Mockingbird, Lett was found guilty on thin evidence by an all-white male jury and sentenced to death. However, his sentence was commuted by then-Alabama Governor Benjamin Miller, who deemed the evidence insufficient. Lett nevertheless died four years later, stricken first by mental illness, then, in the mental hospital where he was confined, by fatal tuberculosis.

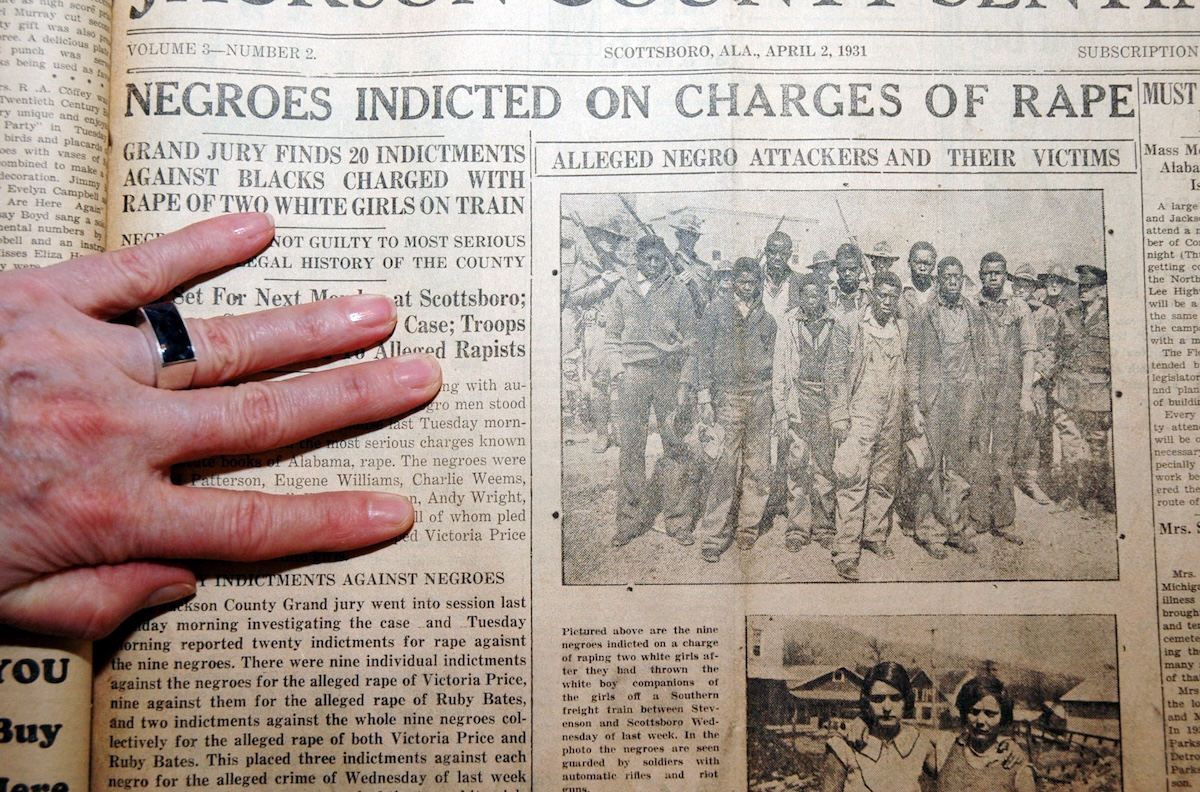

The Lett case was one of numerous similar cases, which include, famously, the Scottsboro boys. They were nine Black teens falsely accused and convicted of the rape of two white women, also in rural Alabama.

A truly abhorrent lynching occurred here in Georgia. It was one of the last cases of a mass public lynching—defined as an extrajudicial killing by a mob, without due process—in U.S. history, and it happened 70 miles from Clarkesville, and not in the early century “heyday” of the Klan, but in the 1940s. One of the victims was a World War II combat veteran. The gruesome lynching is described as follows by the Equal Justice Initiative, a Montgomery, Alabama-based civil rights organization. The account is echoed in many news sources, and there is even a fictionalized, book-length account of the subsequent trial, published years later.

The Malcolms and the Dorseys

On July 25, 1946, a white mob lynched two Black couples near Moore’s Ford Bridge in Walton County, Georgia. The couples killed were George W. and Mae Murray Dorsey and Dorothy and Roger Malcolm. Mrs. Malcolm was seven months pregnant. Mr. Dorsey, a World War II veteran who had served in the Pacific for five years, had been home for only nine months.

On July 11, Roger Malcolm had been arrested after allegedly stabbing a white farmer named Barnette Hester during a fight. On the fateful day, J. Loy Harrison, the white landowner who employed the Malcolms and the Dorseys as sharecroppers, drove Mrs. Malcolm and the Dorseys to the county jail to post a $600 bond and retrieve Mr. Malcolm. On their way back to the farm, the car was stopped at the bridge by a mob of 30 armed, unmasked white men who seized Mr. Malcolm and Mr. Dorsey and tied them to a large oak tree. Mrs. Malcolm recognized members of the mob, and when she called them by name to spare her husband, the mob seized her and Mrs. Dorsey. [It was later reported that during the ensuing massacre, Mrs. Malcolm’s unborn baby was cut out of her womb.] Mr. Harrison watched as the white men shot all four people 60 times at close range. He later claimed he could not identify any members of the mob, though some were his neighbors.

The Moore’s Ford Bridge lynchings drew national attention, leading President Harry Truman to order a federal investigation and offer $12,500 for information leading to a conviction. A Walton County grand jury returned no indictments, and the perpetrators were never held accountable. The FBI [much later] reopened its investigation into the lynching, only to encounter continued silence and obstruction…In response to charges that he was withholding information, Walton County Superior Court Judge Marvin Sorrells, whose father worked for Walton County law enforcement in 1946, vowed that “until the last person of my daddy’s generation dies, no one will talk.”

The Moore’s Ford Bridge inspired an annual memorial march, and a historical marker now stands at a spot near the scene of the crime.

Another soldier murdered for being Black

As previously reported by Now Habersham, local citizens held a memorial event for another lynching involving Black military men in Madison County last year, on its 60th anniversary.

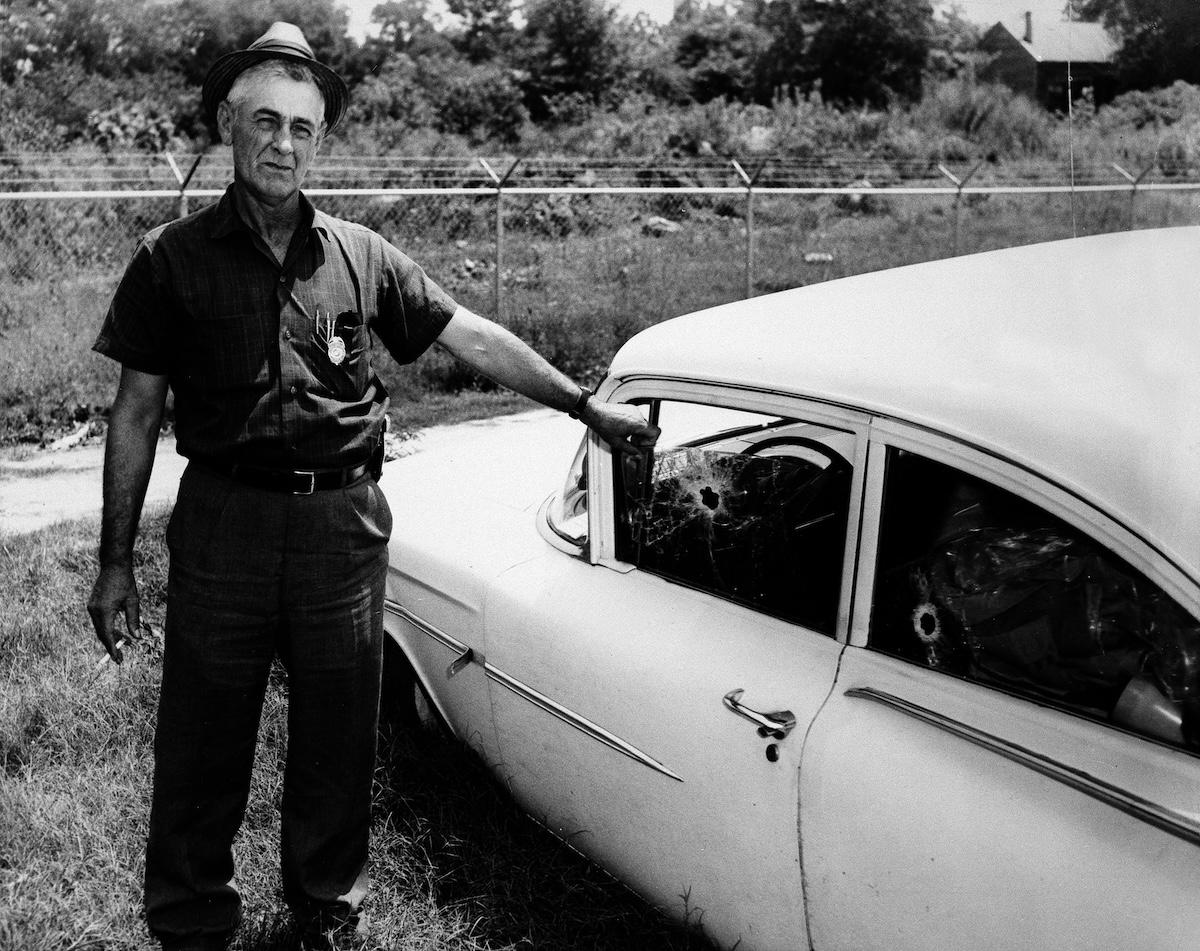

In 1964, Lt. Col. Lemuel Penn, an Army reservist, was driving with two other Black servicemen, Major Charles Brown and Lt. Col. John Howard, from Fort Benning, in Columbus, Ga. to Washington, D.C. As they passed through Athens, the soldiers were targeted and followed by a group of Klansmen. When they crossed the Broad River to the Madison County side, the Klansmen’s car pulled alongside the servicemen’s car, and its occupants fired multiple shotgun blasts at the soldiers, mortally wounding Penn. Brown and Howard survived and kept the car from veering into the river.

Three suspects were arrested but subsequently acquitted by an all-white jury. Two of them were then tried in federal court and received five-year sentences—an unusually short sentence for cold-blooded murder.

The widespread North Georgia Klan

In Georgia and throughout the country, the Klan, sometimes in secret and sometimes openly, perpetrated many other acts of racial violence; the state and its environs had several chapters of that virulently racist, national organization.

In Invisible Empire: A History of the Ku Klux Klan in Twentieth Century Georgia, University of Georgia scholar Clement Charlton Moseley describes many of the Klan’s local activities. Among the “Klaverns” of the United Klans of America, Inc., Moseley writes, were chapters in Clarkesville, Cleveland, Gainesville, and Elberton. The National Knights of the KKK, a brother group, had a chapter nearby in Hartwell.

Moseley quotes area Klan leaders and their open hatred in some detail. Grand Dragon James H. “Bick” Bickley, in South Carolina, was quoted in 1957 saying “I ain’t got nothing against [n-word]….I don’t believe most of them would be causing any trouble if it wasn’t for the NAACP (the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) and the Jews. I understand there are a lot of Communists behind this thing, trying to get us to integrate with the [n-word] so we’ll breed down the race.”

UGA ‘Welcomes’ Its First Black Students

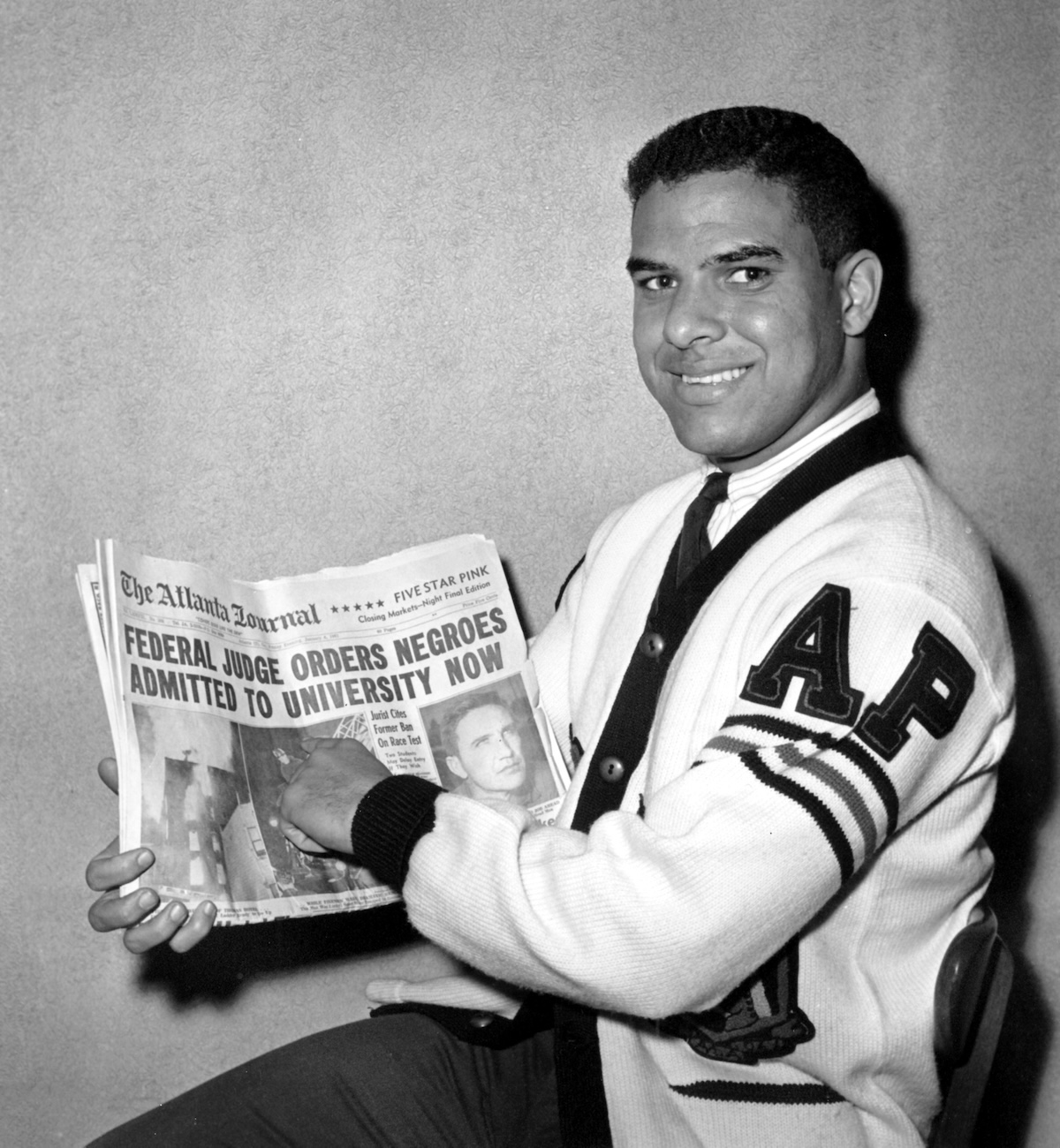

In Athens, a riot ensued at the University of Georgia when its first two Black students, Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes, were admitted in 1961. The two scholars later became, respectively, an internationally famous New York Times and NPR journalist and a celebrated orthopedic physician and medical school professor at Emory University.

But they were not quite so celebrated as students.

After a basketball game the night of January 11, shortly after Hunter and Holmes were admitted, the Athens campus erupted into one of the worst nights the South experienced during the integration crisis. A mob estimated at 2,000 students, townspeople, and Klansmen milled around the dormitory to which Hunter had been assigned. The mob stoned the dorm’s windows, set fires around campus, and fought openly with police attempting to maintain order. The police arrested nine outsiders, of whom eight were Atlanta Klansmen.

Promising Loyalty…and Hate

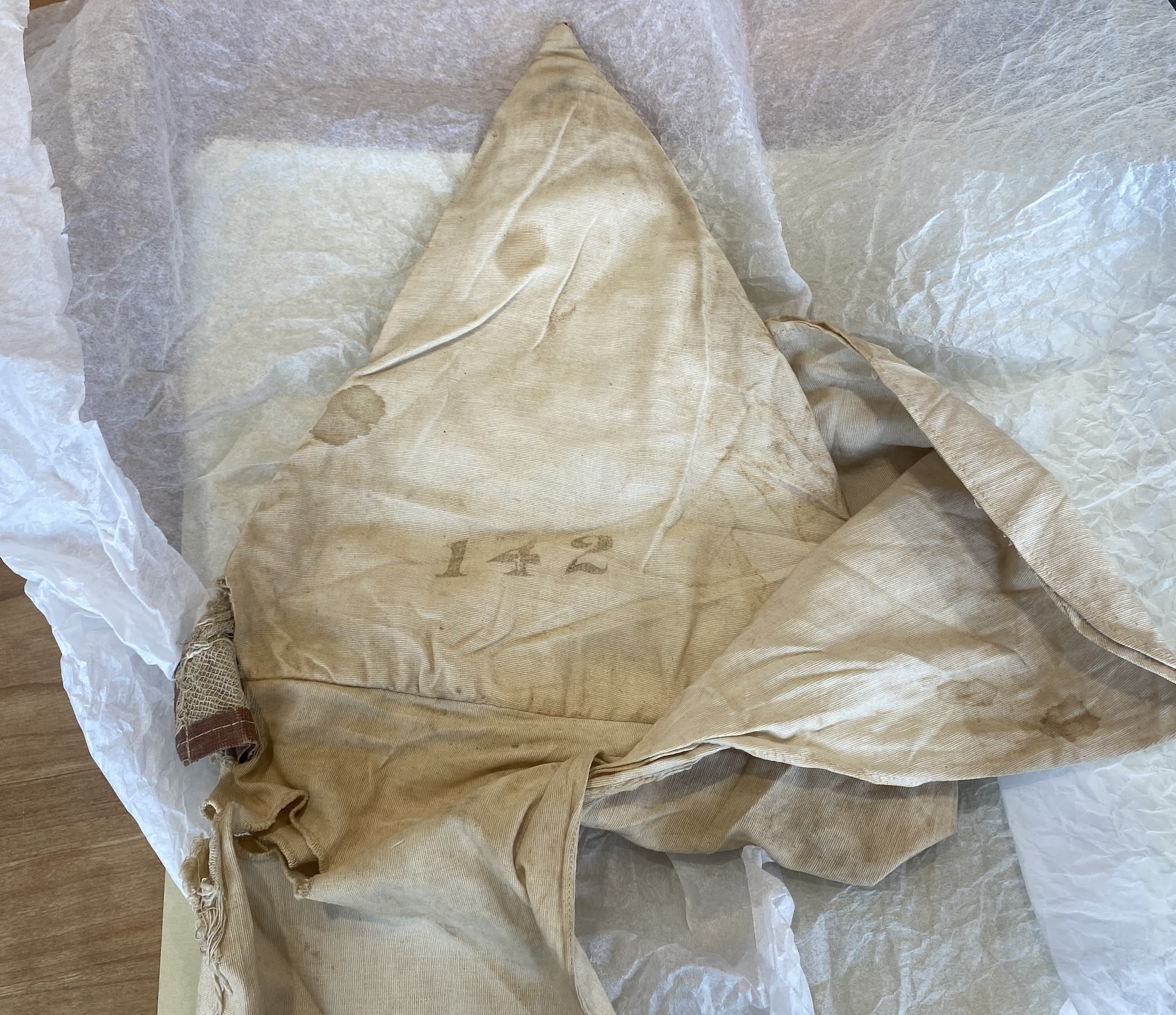

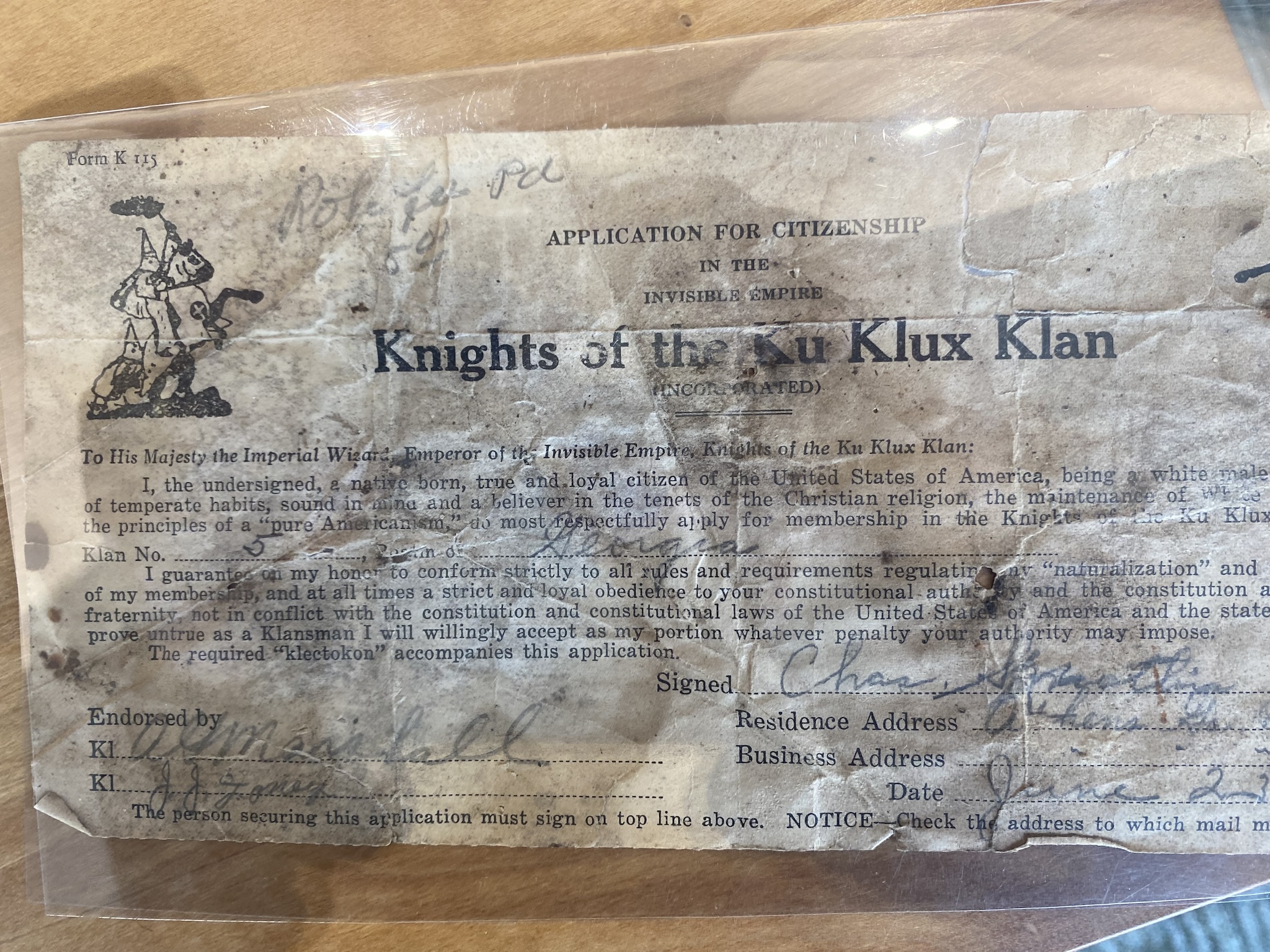

In the special collections at the University of Georgia library, one can still find a Klan hood that was part of the uniform, a badge from the group, and the actual membership pledge of a young man promising loyalty to his new “brothers.” The document reads:

To the Majesty the Imperial Wizard Emperor of the INVISIBLE EMPIRE, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan:

I, the undersigned, a native born, true and loyal citizen of the United States of America, being a white male Gentile person of temperate habits, sound in mind and a believer in the tenets of the Christian religion, the maintenance of White Supremacy and the principles of a “pure Americanism,” do most respectfully apply for membership in the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan through Klan No. (5) (illegible here) …Georgia.

If I prove untrue as a Klansman I will willingly accept as my portion whatever penalty your authority may impose.

The document is dated June 23, 1925, followed by the name “Chas,” an illegible surname, and the man’s age of 18 and his residence in Athens.

At the time, it appears, no one thought to question how the tenets of Christianity square with Klan ideas. As Galatians 3:28 tells us: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.”

And the Klan’s “pure Americanism” also seems to be at odds with the Declaration of Independence’s view that “All Men Are Created Equal,” later expanded and clarified to embrace Americans of all races by the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The Klan, nevertheless, was and is dedicated to the permanent subjugation of its Black neighbors, and as recently as 1987, propagated its views at a Klan rally in Cumming, Georgia, covered by the publisher of Now Habersham when she worked for another news outlet.

‘Tara’ in Clarkesville?

The Georgia racial past is checkered, to say the least. Even here in Clarkesville, with our integrated high school, businesses, and restaurants, the Jim Crow past is recent enough that some of our older residents still remember it.

An elderly lifelong Habersham resident we’ll call Mary is part of the living history of Habersham County. She’s lived in the county most of her 93 years.

Even in the early years of the century, Mary says she doesn’t ever remember being told there were any meaningful differences between the races—and even less, that any one was inherently superior to anyone else. She and a little Black girl her family knew played together regularly, much as sisters might have.

But in downtown Clarkesville, there were unspoken rules. When the epic movie Gone with the Wind came out in 1939, Mary, then seven or eight years old, was desperate to see it. Its characters, Black slaves and white slaveholders, live through and survive the Civil War on a Georgia plantation, the famed “Tara.” Young Mary made a special trip to Clarkesville from miles away to see it at the old movie house on Washington Street that is now the home of Habersham Community Theater, where we began.

Mary sat on the lobby level of the theater with her friends. Upstairs, she remembers, were Black filmgoers, seated in the only seats they were allowed to occupy. “I don’t remember if there was a sign or anything,” Mary says, “but…we just knew. They did, too.”