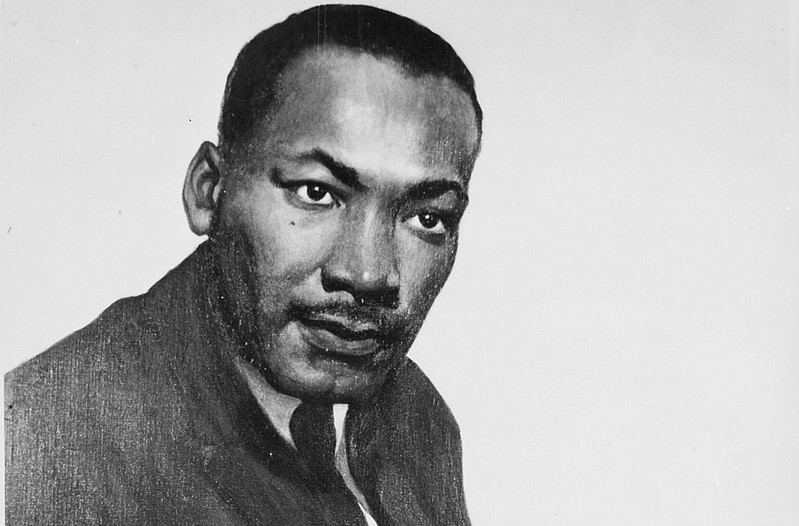

Georgia holds a central place in the story of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a man who fought for social justice and civil rights for America’s Black citizens and continues to inspire change today. While his impact may be seen most obviously in Atlanta, from his birthplace to his legacy at Ebenezer Baptist Church, his impact was also evident in Northeast Georgia.

Lilian E. Smith, a white woman who operated a girls’ camp in Clayton, was a voice for desegregation, gender and racial equality and an open supporter of the civil rights movement. Smith taught these ideas of racial equality at her camp and would go on to write “Strange Fruit,” the best-selling novel surrounding an interracial relationship that challenged racist norms.

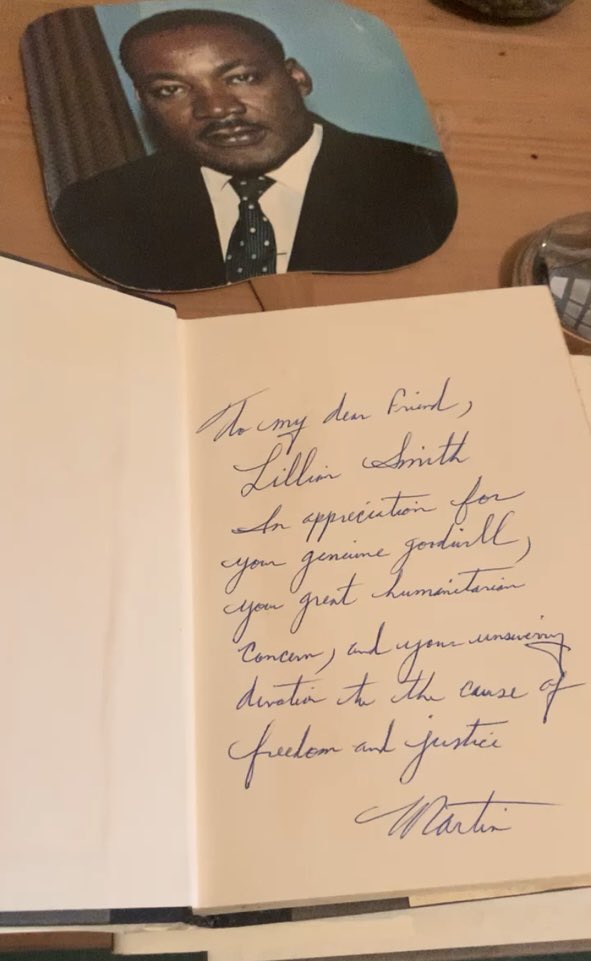

Smith and King began corresponding in 1956, building a friendship as they fought together for King’s dream: an America without racism.

“King respected Smith, not just as a fellow anti-racist and Civil Rights activist,” Piedmont University Lillian E. Smith Center Director Matthew Teutsch wrote in an essay for the African American Intellectual History Society. “He respected her as a friend, and she respected him as a friend.”

They both noted each other in key speeches and letters that fueled the civil rights movement, like in King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” he writes that Smith has “written about our struggle in eloquent, prophetic, and understanding terms.”

When King was arrested in Atlanta before he was pardoned by President John. F. Kennedy, a piece of the story gets left out: he was in the car with Smith.

“We do not get that he was pulled over, before the cop even knew who he was, for having Lillian Smith, a white woman and his friend, in the front seat with him,” Teutsch writes for AAIHS. “We do not get that he was taking her to the hospital after they ate dinner together. We do not get that the two had a correspondence and relationship. We need that part of the story. We need to see the work that King and Smith did together, the thoughts they shared, the words they wrote to one another. We need their relationship in our memory.”

As we reflect today on the legacy King left the United States and the world, remembering his impact in all the corners of the country, Teutsch says we must remember the change he fought for and how it was received.

“We need to recall the backlash King faced during his lifetime,” Teutsch tells Now Habersham. “I came across articles in my hometown newspaper, The Shreveport Times, about the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom where writers said that the march and the movement ignored the laws, laws that, as we know, subjected Black men, women, and children to noncitizenship and oppression.”

Teutsch tells Now Habersham to achieve King’s dream, which he, Smith and so many other activists fought for, we must also acknowledge that the issues they pushed against aren’t ones that vanish overnight.

“Ultimately, we need [to] remember that in order to achieve the Beloved Community that King fought for, and I’d say that Lillian Smith fought for, we must remember that the issues that King and Smith fought against do not go away so easily,” Teutsch says. “As King put it at the end of ‘A Testament of Hope’ when he links Civil Rights Activists to the Founders of the United States, ‘Today’s dissenters tell the complacent majority that the time has come when further evasion of social responsibility in a turbulent world will court disaster and death. America has not yet changed because so many think it need not change, but this is the illusion of the damned.'”