“Hunger affects children in so many ways. Tummy aches and tears were common. Certainly, their attention to learning is hindered.” That’s how retired Habersham County school teacher Britt Cody describes the impact hunger has on students. She witnessed it first-hand throughout her education career.

It’s a problem local food banks, nonprofits, schools, and churches partner together to overcome. The government, too, plays a significant role.

In Georgia, the need to help families and children who are food insecure is a year-round effort. The Food Bank of Northeast Georgia has developed several programs to meet children’s nutritional needs throughout the year, and going back to school creates an opportunity to help those who may have been overlooked during the summer.

Food Insecurity in Northeast Georgia

The U.S. government defines food insecurity as “a lack of consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life.” Feeding America, a national organization that collects food from food producers and retailers to help feed families, explains that food insecurity is not the same thing as being physically hungry. “Food insecurity refers to the lack of available financial resources for food at the household level.” Over 22 million children in the United States experience true hunger during the summer months.

Erin Barger, the president and CEO of the Food Bank of Northeast Georgia, has specific numbers of children who are food insecure in the immediate five-county region:

- Banks County has 460 children who are food insecure, and 12.7% of its general population is food insecure.

- Habersham County has 970 children who are food insecure, and 11.8% of its general population is food insecure.

- Rabun County has 460 children who are food insecure, and 15.5% of its general population is food insecure.

- Stephens County has 720 children who are food insecure, and 13.6% of its general population is food insecure.

- White County has 580 children who are food insecure, and 11.7% of its general population is food insecure.

Barger shares, “Schools have become an invaluable role as food distribution centers. During the summer, the Seamless Summer program provides lunches to children in many of our counties, and our Food to Kids 360 program provides assistance as well.” Barger would like to see this program expanded through financial donations, food donations, and partnerships. “The only way we will solve the problem of food insecurity is to partner our way out of it,” Barger emphasizes. “We want to develop partner relationships with other agencies and nutritionists to work together on meeting the need.”

During the school year, children who are food insecure have access to free lunches.

“During the Pandemic, universal free lunches met that need,” Barger explains. “But that program has come to an end now. Parents have had to reapply for free lunches for their children.”

Providing lunches is just part of solving the issues for children who are food insecure. Barger says the Food 2 Kids program has been designed to address the most essential need for food insecure children by providing food for the weekend.

The Food 2 Kids program sends weekend meal bags to over 1,500 area students each week who have been identified by teachers and school counselors as chronically hungry. Within each bag are six meals and healthy snacks. The bags weigh approximately 6.2 lbs and are delivered directly to students at school by volunteers.

Helping provide snacks at school

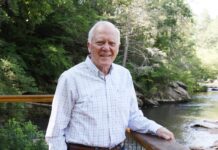

Cody taught for thirty years at Clarkesville Elementary School. What she saw as a teacher has made her passionate about helping provide snacks at schools for students who don’t have any.

“For all classrooms, there are always low-income children, whose parents simply don’t have the money to give them snacks. From lunch to going home is a long time, so the afternoons can be hard on those children,” Cody says.

She noticed other things about these students as well, from tummy aches and limited attention spans to feelings of being overlooked.

“Honestly, the children also felt the emotional impact as others were loved in ways they were not.”

Cody noticed, too, that some children would arrive at school late, missing the breakfast provided there, and without having eaten at home.

“A snack would always put a smile on their faces and help them approach the day stronger.”

As a teacher, Bitt Cody was blessed with compassionate parents as partners who would help her provide snacks for children who couldn’t provide their own. “When teachers don’t have this support,” Cody says, “teachers simply buy the snacks on their own. On average, most teachers probably spend at least $1,000 a year on supplies and snacks. Having a community partner is such a huge help!”

Churches and individuals in the area can “adopt” a class or a grade at one of the local schools and make sure those snacks are provided monthly. Getting started is as easy as calling your local elementary school and finding out what help is needed.