This third and final installment of Lessons from Cuba, is a little awkward given that we are just a few days away from Father’s Day. Yes, the essay is about a father and son relationship, but their story does not end happily. Perhaps the lesson in this segment is in providing fathers an opportunity to think about the relationship they have with their children. It is about examining what matters in families and what matters in our community. At least that is my hope.

This final segment shares the story of why I originally felt so compelled to travel to Cuba as a journalist to see a little community called San Francisco de Paula, where Ernest Hemingway’s home was located during twenty years of his most prolific writing. His compound, taken over by the Castro’s following the American embargo in the early 1960s, was named Finca Vigia, meaning “lookout farm.” Hemingway purchased it in 1939 for $12,500, royalty from For Whom the Bell Tolls. Today, it includes eleven lush tropical acres on a high point west of Havana, where from his writing tower, he could see the Caribbean Sea. He and his third wife, journalist Martha Gellhorn, lived there and it is where he wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls and Old Man and the Sea.

Finca Vigia, is a marked contrast to his Key West home, where he and his second wife Pauline Phifer, married and raised two of their three sons, Patrick and Gregory. The Key West home sits on a small lot adjacent to the Key West lighthouse where the boys played as children, and a stone’s throw from Sloppy Joe’s, the bar made famous by Hemingway’s late night drinking, carousing and bragging. After Ernest and Pauline divorced, Hemingway married Martha Geller, a noted journalist who once said, “I hated every second the man made love to me.” Their sordid relationship is played out on the silver screen in the 2012 HBO film, Hemingway and Gellhorn.

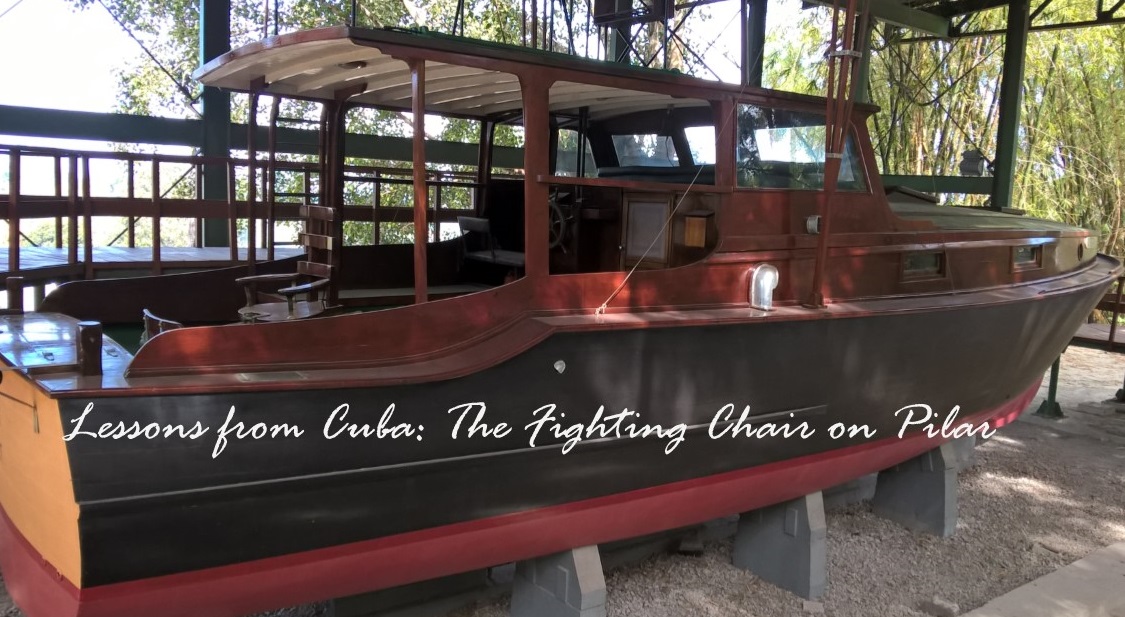

The exact and specific reason I went to Finca Vigia was to see Pilar, Hemingway’s famous fishing vessel. It is a mini-yacht built for the author in Brooklyn, New York in 1934. I wanted to photograph Pilar’s fighting chair, the place where Hemingway, and friends strapped themselves in, to catch Marlin, Sailfish and smaller Mahi-mahi. It was this chair that mesmerized me as a fisherman, and writer, and a father.

I wanted to see the place that youngest son, Gregory, was seldom invited to sit during his teenage years and after. A place only fit for masculine, manly-men, who passed muster with the king of American male-themed stories of bull fighting, fishing and hunting-down wild life in Africa and India and Montana.

Papa Hemingway gave his youngest son, a superb athlete, he nickname Gigi, as a young boy. From early writings, though, America’s Pulitzer Prize and Noble Prize literary giant questioned his own love for Gregory. In Islands of the Stream, Hemingway fictionally wrote about his three boys, describing young Gregory this way, “He was a boy born to be quite wicked who was being very good and he carried his wickedness around with him transmuted into a sort of teasing gaiety. But he was a bad boy and the others knew it and he knew it. He was just being good while his badness grew inside him.”

So, it isn’t odd to understand the complicated summer that young fourteen year old Gregory came to Cuba to visit Papa and step mother, Martha Gellhorn. As a secret diversion, Gregory apparently took his step mother’s silk lingerie, wore them at night and hid them under his own mattress, where they were discovered after he returned to private boarding school in Connecticut late in the summer of 1947. While Gregory blamed the Hemingway maid for placing the personal clothing under his mattress, the truth emerged the following summer. And the realization that his son was a cross-dresser began the downward spiral and destructive relationship between father and son.

Standing on the hillside behind Finca Vigia, amazed at the famous Pilar, and her fighting chair, in which Hemingway had spent over two decades defining male masculinity with his male companions, each taking a seat and battling nature in the form of a Marlin. Errol Flynn, Spencer Tracey and others smoking away on Cuban Cohiba cigars, shots of scotch on ice, portrayed what it meant to be truly masculine, while hooking some of the largest fish in the Caribbean.

But Gregory was never invited to Pilar after making his revelation known. In fact, while in medical school in Miami, Gregory continued cross dressing and was arrested for possession of narcotics. After he was released from jail, elder Hemingway made a quick trip to Key West and confronted Gregory, in front of Pauline. The angry confrontation pushed Pauline into a heart-related collapse and she died hours later. For the rest of their lives, Ernest and his son Gregory blamed each other for Pauline’s death, and seldom spoke to each other again.

Just a year after Hemingway left Finca Vigia and Cuba, while tending to cancer, drinking heavily and mentally absorbed in his broken relationship with his youngest son, and guilt over Pauline’s sudden death, Papa killed himself in Ketchum, Idaho. The writer’s own father had ended his life the same way, as well as several other Hemingway family members.

The irony to me, as I photographed that famous chair in the back of Pilar, was that Gregory did not end his own life. He became a physician, practiced medicine most of his career in Montana and Wyoming, had electroshock therapy many times in an attempt to rid himself of his desire to cross dress, married four times, had eight children, and died of natural causes in 2001.

Sadly, Gregory Hemingway died in a Miami jail for women. He had been arrested in Key Biscayne Park, dressed in a red dress and high heels, intoxicated, without diabetes and blood pressure medicine, and misunderstood by the law enforcement personnel running the jail. No one believed that he was a child of Ernest Hemingway (he identified himself as Gloria Hemingway to officials). After 48 hours in his jail cell, without medical treatment, he died of a cardiac arrest.

When I look at the fighting chair there on Pilar, I do not see Ernest Hemingway, Spencer Tracey or Errol Flynn or any of the other masculine giants of film and literary world of the 19th century.

When I look at the fighting chair there on Pilar, I do not see Ernest Hemingway, Spencer Tracey or Errol Flynn or any of the other masculine giants of film and literary world of the 19th century.

I see Gregory.

I see a man who was greatly perplexed about who he felt he was – inside. A man who from his earliest days had desires he felt he could not control. He may have had weaknesses, but Gregory was one Hemingway who fought a difficult life with passion, and though he could have easily taken his own life, he did not. We have a great lesson to learn about what family matters and what community matters, during the tragic aftermath of Orlando this Father’s Day.

Gregory Hemingway is one Hemingway who truly deserves to have a seat in the fighting chair.