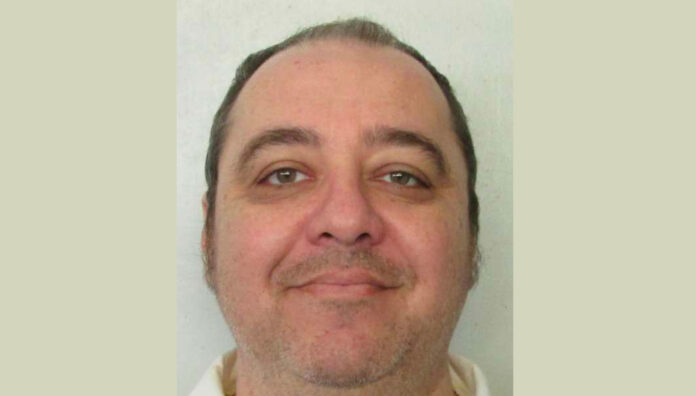

(States Newsroom) — The state of Alabama Thursday executed Kenneth Eugene Smith for the 1988 murder-for-hire of Elizabeth Sennett.

The execution, the first ever carried out with nitrogen gas, began at 7:56 p.m., according to the Alabama Attorney General’s office. Smith was pronounced dead at 8:25 p.m.

Smith, 58, made a final statement through a mask which muffled his words.

“Tonight, Alabama caused humanity to take a step backwards,” Smith said. “I leave with love, peace and light. I love all of you. Thank you for supporting me.”

Media witnesses, including a reporter from Alabama Reflector, saw him dressed in his prison uniform but covered in white sheet up to his chest. Smith laid in the gurney with a slight incline with is arms extended to his side. He was strapped down in two places, one around his stomach and another around his upper chest.

After the death warrant was read and Rev. Jeff Hood, Smith’s spiritual advisor, performed last rites, a staff member closed a vent on the mask, which began the flow of nitrogen. Smith convulsed for two minutes, with seven minutes of heavy breathing, with Smith taking large breaths.

John Hamm, commissioner of the Alabama Department of Corrections, said that it “appeared that Smith was holding his breath as long as he could.”

“That was all expected and in the side effects that we have seen, or researched, on nitrogen hypoxia,” he said.” Nothing was out of the ordinary from what we were expecting.”

Sennett’s husband, the Rev. Charles Sennett, hired Smith; John Forrest Parker and Billy Gray Williams to kill his wife in order to collect insurance money. Parker and Smith entered the home where Elizabeth Sennett was killed. All three were convicted of her death. Parker was executed in 2010; Williams, sentenced to life in prison, died in 2020.

Rev. Charles Sennett died by suicide a week after his wife’s death.

Michael Sennett, Elizabeth Sennett’s son, said after the press conference that Parker and Smith had “been incarcerated almost twice as long as I knew my mom.”

“All three of the people involved in this case years ago, we have forgiven them, not today but we have in the past,” he said.

Smith, who survived a botched execution in November 2022, spent his last 24 hours receiving visits from friends and family, including his wife. He ate a final meal of steak, hash browns and eggs.

The U.S. Supreme Court rejected appeals from Smith on Wednesday and Thursday that argued the method violated his Eighth Amendment protections against cruel and unusual punishment. The court’s three liberal justices dissented.

“Having failed to kill Smith on its first attempt, Alabama has selected him as its ‘guinea pig’ to test a method of execution never attempted before,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote. “The world is watching.”

In a statement Thursday afternoon, Smith and Rev. Jeff Hood, his spiritual advisor, said “the eyes of the world are on this impending moral apocalypse.”

“Our prayer is that people will not turn their heads,” the statement said. “ We simply cannot normalize the suffocation of each other.”

Murder for hire

Smith was convicted and sentenced to death for his role in Sennett’s death in 1989, but the conviction was later overturned. At a subsequent trial in 1996, Smith was again convicted. A jury recommended Smith be sentenced to life in prison. However, the trial judge overruled the jury and imposed the death sentence.

The Alabama Legislature in 2017 abolished the practice, known as judicial override, but did not make it retroactive.

Smith was brought to the death chamber at Holman Correctional Facility in November 2022 for execution by lethal injection. The U.S. Supreme Court gave approval for the execution to proceed about 90 minutes before a death warrant would expire.

The execution was called off after Department of Corrections Department staff failed to establish a second intravenous line necessary for administering the lethal drugs. Smith’s attorneys have said the process, which resulted in multiple puncture wounds, left him with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Death by nitrogen

The Alabama Legislature approved nitrogen executions in 2018. At the time, Alabama and other states that kill with lethal injection faced shortages of drugs and growing criticism of the use of midazolam, a sedative present in several botched executions, including the 2016 execution of Ronald Bert Smith in Alabama.

Pittman and other supporters argued the nitrogen method would allow the state to continue executions and suggested it would be more humane.

“You basically black out,” Pittman told the Reflector in September. “There is no time for pain or anything else. In fact, nitrous oxide is a way of reducing pain for reducing surgeries.”

Pittman, reached on Thursday, declined comment.

Doctors and anesthesiologists questioned that conclusion. The American Veterinary Medical Association discourages the use of nitrogen in euthanizing animals, in part because of the difficulty of keeping oxygen out, which can prolong death.

“I can’t even begin to imagine what it is like to be in the shoes of someone who is facing execution, but to be waiting for that moment, and to know that you are undergoing a method of execution that is not tested and waiting to suffocate, then that seems like that would be an undue amount of suffering,” Dr. Radha Sadacharan, a practicing family physician, told the Reflector in September.

Mississippi and Oklahoma have also adopted the method, though neither state had used it or scheduled an execution by nitrogen as of Thursday.

The 2018 law also established a 30-day window for people on death row to choose the method.

But attorneys and those incarcerated told the Montgomery Advertiser in 2019 that they were only told of the option days before a deadline, which created confusion.

Many death row inmates are represented by lawyers who live outside Alabama and some had limited time to understand what a nitrogen execution might entail. A federal judge in 2021 called the state’s notification “a mess.”

Appeals

Smith did not originally choose to be executed by nitrogen gas, though he expressed his preference for it in a 2022 court filing.

“The execution was lawfully carried out by nitrogen hypoxia, the method previously requested by Mr. Smith as an alternative to lethal injection,” Gov. Kay Ivey said in a statement Thursday. “At long last, Mr. Smith got what he asked for, and this case can finally be put to rest.”

Attorneys for Smith challenged the protocol the state planned to use and the fact that Smith would be the first person it was used on. They also said the mask employed in the procedure could prevent him from praying aloud during the execution.

Smith’s lawyers argued that the mask itself might not fit tightly on his face and so would allow oxygen to creep in, which could prolong his death and cause him to vomit. His attorneys also argued that the state had unconstitutionally moved Smith’s execution up ahead of others on death row who had chosen to die by nitrogen hypoxia and who had exhausted their appeals.

Attorneys for the Alabama attorney general’s office countered that the state had taken precautions to ensure Smith would be exposed to pure nitrogen and that harms were theoretical.

The federal courts sided with the state. U.S. District Judge R. Austin Huffaker Jr. ruled on Jan. 10 that Smith had not provided a sufficient reason to stop the execution, calling the allegations and evidence “speculation.”

A divided three-judge panel of the U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Huffaker’s ruling on Wednesday.

“There is no doubt that death by nitrogen hypoxia is both new and novel,” the unsigned opinion said. “Because we are bound by Supreme Court precedent, Smith cannot say that the use of nitrogen hypoxia, as a new and novel method, will amount to cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment by itself.”

U.S. Circuit Judge Charles Wilson concurred but wrote that he feared Smith might face “a cruel and unusual execution” if the gas led him to choke on his own vomit. U.S. Circuit Judge Jill Pryor dissented, writing that Smith’s PTSD made it very likely for him to face that scenario.

“The cost, I fear, will be Mr. Smith’s human dignity, and ours,” she wrote.