Georgia is now one of 25 states allowing people to write directions for their future mental health care just in case they experience a behavioral health crisis.

Psychiatric advance directives, or PADs, were authorized by law in Georgia last year, though not many people have heard of them.

That’s why Ellyn Jaeger and Stephanie Diaz spoke about the legal document during a panel at the 2023 National Alliance of Mental Illness conference in Atlanta earlier this month.

They are with the Georgia Office of Advocacy, but Jaeger had been working for years to make a legal document that specifically mentions mental health as opposed to only alerting about physical conditions like diabetes.

This law is an important development for Georgia residents who have experienced a mental health crisis, have a mental health diagnosis, or have a family member with a mental health diagnosis. House Bill 752 allows Georgia residents to plan and maintain their independence when it comes to treatment and care.

“This legislation was brought up and failed for at least 12 years consecutively, which is a very, very long time to work on something,” Jaeger said. “And then there was a bit of a break and then we came back and we gave it another shot. And again, it failed.”

She said there is no official rollout and her office’s goal is to raise awareness.

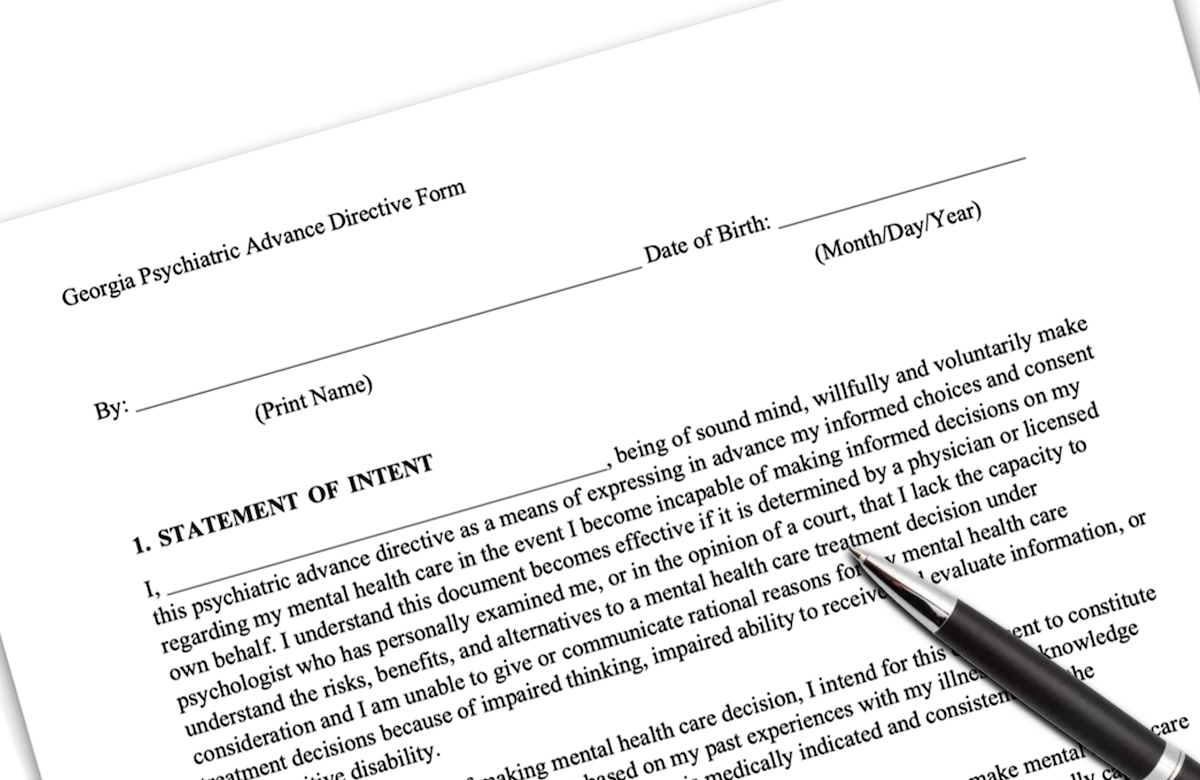

A PAD allows someone to record their preferences now for future mental health care and even names someone to make treatment decisions in the event the author loses behavioral control.

It’s like a medical alert bracelet explicitly for mental health.

But the way advanced directive documents were set up for physical ailments did not offer an opportunity to talk about mental health emergencies.

“It’s strictly if you go into a coma, if this happens, that happens,” Jaeger said. “There’s no mention of mental health at all. And so a psychiatric advance directive is just that. It’s about what’s happening to you mentally.”

Jaeger said that when she was vetting the legislation to see if she wanted to get involved, she asked her public defender daughter’s opinion.

“‘Mom, if I’m defending somebody, it’s really important that I hear their words,'” Jaeger quoted her daughter. “She said, ‘The PAD helps me understand their real thinking. Not the crisis thinking, but the real thinking.'”

PADs can be shared with local hospitals, health providers and police departments, so the author’s preference for care is clear in a crisis.

“When you lose that control, everybody stops listening.” Jaeger said. “The PAD keeps your control. The PAD says exactly what you would like to say and articulates in a way that you would like to say it without you having to do it at that moment.”

Georgians can visit NAMI’s website and find a flyer with more information, instructions and a fillable form to create a PAD.