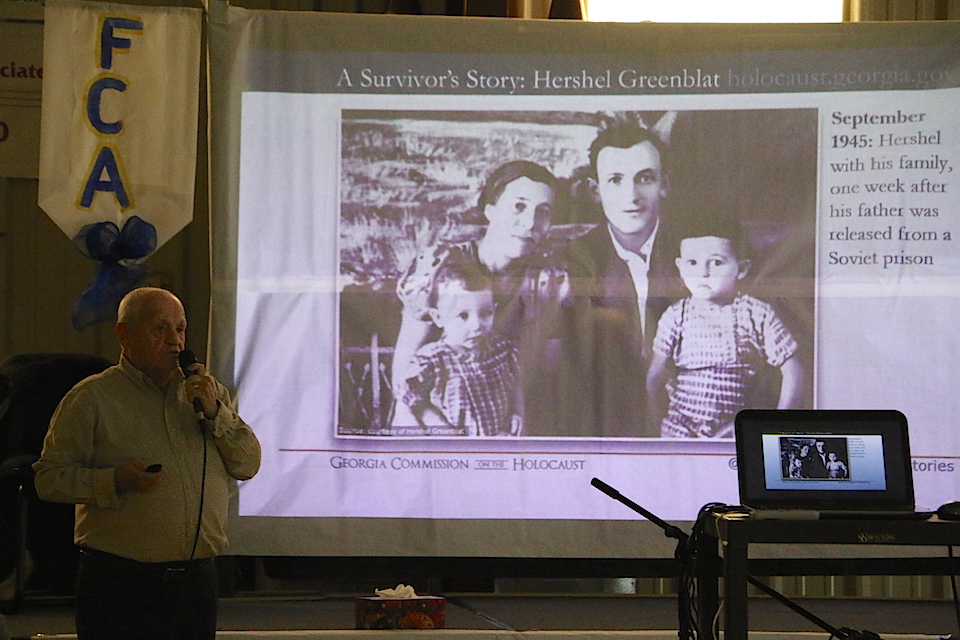

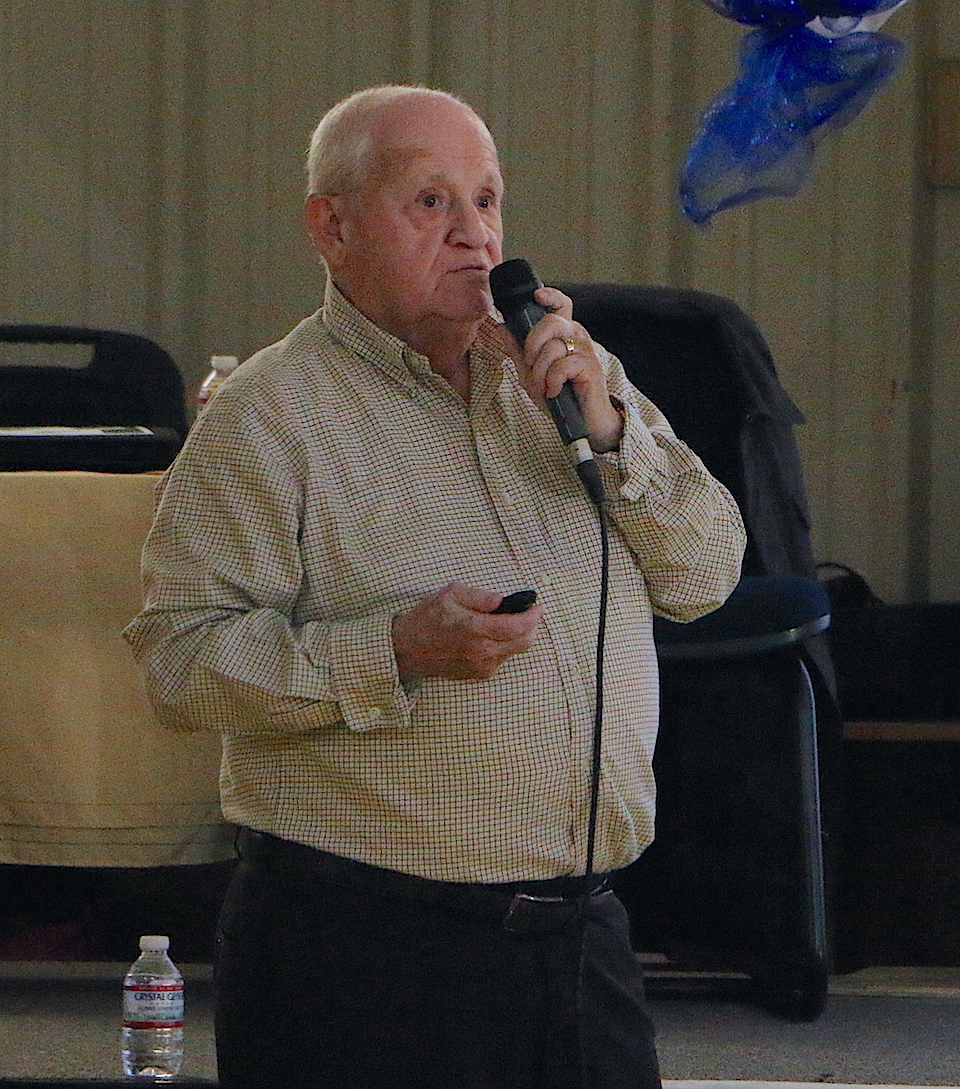

Holocaust survivor Hershel Greenblat of Atlanta speaks to a crowd at Faith Christian Academy on February 27. Students from FCA, FCA Co-op and White Creek Christian Academy attended along with dozens of parents and other community members.

He spent the first year and a half of his life hiding in a cave. Most of his extended family was slaughtered by Hitler’s death squads.

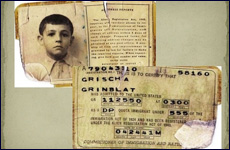

Grischa Grinblat survived.

Today, the 76-year-old great-grandfather from Atlanta is among the dwindling number of Holocaust survivors. He’s a living witness to one of the worst atrocities in world history.

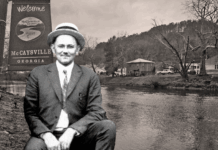

Grinblat – whose name was changed to Hershel Greenblat when his family moved to America – recently shared his story in Habersham County. He spoke with close to 200 people during a presentation Tuesday at Faith Christian Academy in Mt. Airy.

“I wanted it (the Holocaust) to be more than just a statistic,” said FCA Social Studies teacher Tiffany Collins who organized the event. “A lot of times we just look at a book and we can say ‘six million people died’ and we don’t have a face with that. I really wanted my students to be able to see a face.”

They did. In Greenblat they saw the face of a man who survived barbaric hatred and the faces of his loved ones who didn’t.

A survivor’s story

Greenblat was born on April 24, 1941. His parents, Manya and Abraham, were resistance fighters against the German Army. They lived in hiding with other Jews in a cave known as Priest’s Grotto, part of an expansive Gypsum cave system southwest of Kiev in the Ukraine. “That’s where I began,” Hershel said.

As he shared his intriguing story of survival the audience sat quietly, absorbing the details of a time most had only read about or seen in movies and on TV.

He told how his mother was seriously wounded by shrapnel while foraging for food and supplies. His parents left him with friends underground while they went to a “safe” hospital 45 miles away. Greenblat didn’t see his parents again for nine weeks. When the family was reunited, his father decided to move farther east to stay ahead of the advancing German Army.

The young family left the refuge of the cave for a town called Krasnodar.

…we became a non-entity. We were nobody.

“That 400 mile trip took us approximately three to four months because we had to make sure that we weren’t going to be detected and that our path was safe,” Greenblat said. “We had to hide our Judaism. My father took every piece of identification that we had and destroyed it.”

With no official record of their names or personal histories, Greenblat said “we became a non-entity. We were nobody.”

In Krasnodar, Greenblat’s parents found ways to survive. His mother begged and worked for food cleaning houses and toilets and doing other odd jobs. His father took a job in the bakery at a nearby Russian Army camp. It was there in March of 1943 that Greenblat said his father made probably “the biggest mistake of his life.” Desperate for food for his family, he tried to steal two loaves of bread. The Russians caught him and put him in prison for the rest of the war.

A month later, Manya gave birth to a daughter. She raised her children alone until her husband was released from prison two and a half years later.

“My father knew that life under Communism wasn’t going to be better than under the Nazis,” Greenblat said. The Jewish families in Krasnodar decided to escape. They got ahold of two cattle cars and a train engine. Greenblat’s family and about twenty others loaded into the cars and headed for Austria. It took them nine months to complete the 1,800 mile journey. Hershel was five years old when they arrived. He still remembers the American soldiers who greeted them.

“These soldiers treated us with kindness. They treated us with respect,” he recalled. “The American soldiers saved us.”

A survivor’s loss

Greenblat’s family escaped the Nazis and Iron Curtain but his Holocaust story doesn’t end there. For several years his family lived in Displaced Persons (DP) camps in Austria. His mother gave birth to another daughter. His father traveled by bicycle to other camps hoping to find relatives. That’s how he learned of their horrible fate.

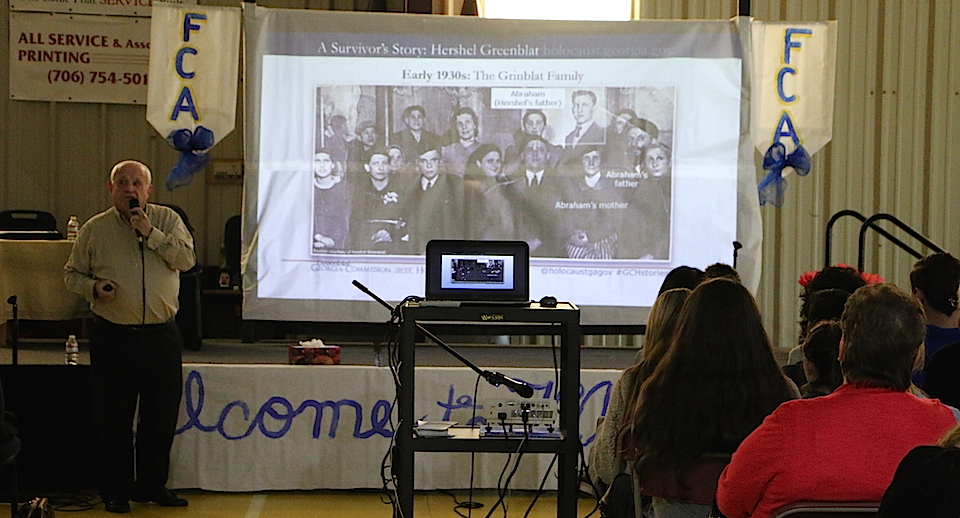

“I never got to know any grandparents, any aunts, uncles, cousins,” Greenblat said as he projected old family photos onto a screen. “At a place called Babi Yar my grandmother, my grandfather, my two uncles, their wives and their children were murdered because they were Jews and no other reason.”

Greenblat shared details of how Hitler’s henchmen killed his mother’s family in the Ukraine.

“They marched people to the fields of Babi Yar. They gave them shovels and they told them to start digging. Men, women, children, seniors, it didn’t matter,” he said. “They made them get naked in front of each other and, as they did, they would line them up on the outskirts of the trench and they would machine gun them.” Babies were thrown into the pit alive, left to die when they were covered up with dirt and dead bodies. From 1941-1943 he said, “110,000 human beings were murdered that way.”

They’re not numbers, they’re human beings.

His father’s family was killed in Poland. “Everyone in this picture, other than my father, was murdered in a way that is almost unspeakable.”

Greenblat related how, in November 1943, German soldiers told his father’s family and others in the Lublin Ghetto they were being moved to work in a factory. The Germans promised them showers and clean clothes. “They lied,” Greenblat said.

“They marched them about a mile and a half to Majdanek Concentration Camp. They made them get undressed, naked. They shaved their heads. They took all their possessions. They pulled out any gold teeth. They took away everything.” Then, the Nazis marched them into a gas chamber and locked the door.

“A few minutes later when all the screaming stopped, they opened the doors, took out the bodies, and shoved them in an oven and destroyed them,” Greenblat said. Looking again at the photo on the screen he added, “Everyone in this picture, other than my father, was murderd because they were Jews.”

A survivor’s hope

It was an immense personal loss, still, Greenblat and his family persevered. They spent several more years living in DP camps in Austria. In November 1950 they made their way to the United States. When the Army transport ship they were on steamed into New York Harbor, Greenblat’s father took him up on deck. There he saw “one of the most beautiful sights I’ve ever seen…the Statue of Liberty.”

Immigration officials processed the family at Ellis Island and relocated them to Atlanta. Abraham bought a grocery store in the Buttermilk Bottom ghetto. The South’s racial divide deeply disturbed him. “My father said, ‘What the heck is wrong with this picture?,” recounted Greenblat. “‘Here we just left persecution because we were Jews and we are in America and people are being persecuted in the United States in the South because they are black.'”

Greenblat’s father owned the store for 17 years and during that time his son says he “paid it forward.” He and his wife helped feed, clothe and get medical attention for those who needed it. Stories of their generosity spread. One day Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. paid Greenblat’s father a visit. The two became close friends.

Hershel Greenblat assimilated into American culture through school. “You are an American,” his teacher told him on his first day of class. Nearly thirty years later, his parents became naturalized citizens. “We had the biggest party you ever saw,” he said.

A survivor’s challenge

He survived the Holocaust, and now Hershel Greenblat has made it his mission to make sure others never forget. He travels all over the state speaking to students in schools and colleges. His story is preserved on video and in the archives of the Breman Museum in Atlanta.

I’m turning the baton over to you.

“Your children will not have the opportunity to listen to a survivor,” he told the students at FCA. “We are dwindling. I’m turning the baton over to you. I want you to talk to your family about what you heard. Talk to your friends about what you heard because it happened. Six million people were killed because of their religion.”

He impressed upon them, “They’re not numbers, they’re human beings.”

Greenblat urged the students to respect their parents, respect their teachers, and “don’t hate.”

“Don’t be a bully,” he implored. “If you see something wrong, do something, say something. Grow up to be decent human beings because, God knows, that’s what this world needs, decent human beings. We have plenty of the other kind.”

FCA 10th grader Brandi Thomas of Clarkesville took Greenblat’s message to heart. “A lot of people nowadays don’t believe the Holocaust even happened,” she said. “Having someone come speak about it means a lot.”

“I hope this is something that they tell their kids and their grandkids,” Collins said of her students. “I hope we can continue Mr. Greenblat’s story even though he might not be here. I know for me, when I talk about the Holocaust, I have a face now and it’s Mr. Greenblat.”