The Georgia Department of Public Health will face some cuts to its available funding, as the federal Department of Health and Human Services confirmed March 26 that it was ending billions in Covid-era grants.

On March 27, the HHS, run by Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., also announced a total restructuring of the department, which includes the dismissal of around 20,000 current employees. HHS oversees the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. Thursday’s announcement indicates that other divisions under the agency’s purview, including the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), will be reorganized into a unified department.

The grants canceled Wednesday were issued during the pandemic to state and community health departments were funneled through the Atlanta-based CDC and SAMHSA.

There’s been no published list of what grants are getting cut, but there is evidence that since the end of the public health emergency, these grants were being used to support work outside of Covid-19 testing and surveillance.

For example, the Georgia Department of Public Health continues to receive money from the Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity Program, which started in 2020 as a funding mechanism to support flexibility in public health’s response to emerging infectious diseases. With that money, Georgia was able to develop its Wastewater Surveillance System and Advanced Molecular Detection program, which is meant to improve the identification and response to infectious diseases like respiratory viruses, foodborne illnesses, and diseases that spread from animals, among others.

The agency was granted $5 million in July 2024 and $604,000 in December under the ELC program.

In anticipation of cuts from the federal government, the Georgia Department of Public Health had already made plans to tighten the belt around its budget.

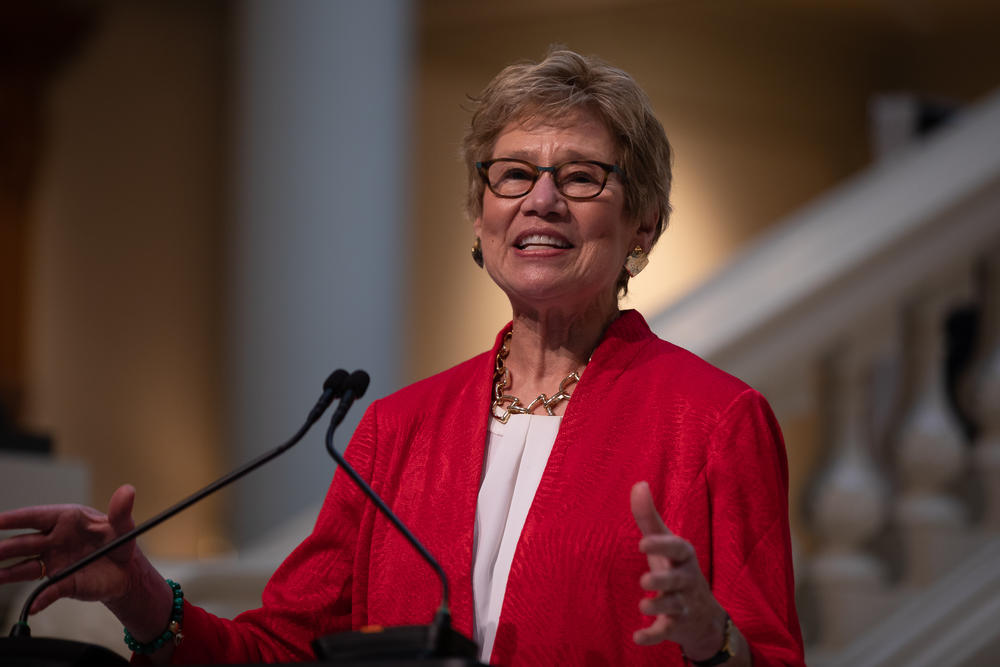

The state agency, which oversees local public health departments in every county, has been taking multiple measures to ensure a “cautious approach to spending” since early February, according to communications between Department Commissioner Kathleen Toomey, Deputy Commissioner Chris Rustin and among other staff, attained by GPB through open records.

Those measures include a pause on non-essential staff travel, including to several annual conferences. In an email, one agency employee likened the restrictions to measures taken during the Covid-19 pandemic.

RELATED: How uncertainty over federal health funding and data is affecting Georgia researchers

They also questioned whether additional efforts to limit spending could include a pause on filling new positions or funding new programs and some moves from in-person to virtual programming.

GPB reached out to DPH for comment and clarity on these measures but did not receive a response on specific decisions to limit spending. Instead, on Thursday, DPH spokesperson Nancy Nydam said the agency is “still analyzing the impact of the federal funding cuts.”

District Health Directors were briefed on budgetary measures in a virtual meeting on Feb. 4, 2025 hosted by Toomey. Meeting notes indicate concerns over the unprecedented fast pace of the current administration, including moves to define and subsequently defund programs considered to be under Diversity, Equity and Inclusion initiatives.

“They’re having to make priority decisions, which, of course, as leaders, we always have to do that,” said Nandi Marshall, president-elect of the American Public Health Association. “However, when your major source of funding may be cut, it’s like, ‘What do we do?’ Like, there’s an entire state of people that we need to provide services to and to protect.”

The Georgia Department of Public Health receives about 50% of its budget from the federal government. Marshall said that funding is vital for programs like WIC — the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children. Over 200,000 low-income people in Georgia use WIC to help feed their children and for nutrition and breastfeeding support.

There’s been no indication that WIC will get cut, but federal congressional budget proposals have indicated major cuts to SNAP, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistant Program, and Medicaid. Millions of low-income adults, kids, and people with disabilities rely on benefits from all three programs to make ends meet. And advocacy organizations warn that since many enrolled in WIC are screened for eligibility through applications to the other two programs, or vice versa, there could be ripple effects in enrollment.

Marshall said she expects that even with cuts to other programs, there could be cuts to staff, which would make it harder for services to be delivered across the board. Many local public health departments, especially in rural areas, are already short-staffed.

“Whether it’s at the federal or state level, loss of funding is going to equate to losing positions,” Marshall said. “We have figured out how to make things happen with less resources. But we do so much better when we have more resources.”

Figuring out how to move forward through planning between local public health workers, scientists, academics and policymakers was made harder with the cancellation of the Georgia Public Health Association conference, she said

“Not being able to have a conference this year was a really big blow,” Marshall said. “I don’t have a planned opportunity where I can sit with other folks on Board of Healths from across the state and ask questions and hear about what’s going on.”

Also put on pause because of travel restrictions is the Immunize Georgia conference, hosted by the Georgia Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Coming at the tail of an extremely active flu season, that gathering would have given immunologists and practitioners a chance to talk about the latest trends in infectious diseases and how to improve prevention.

Meanwhile the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities confirmed it received notification of cuts to SAMHSA funding and is currently examining what impacts they may have across the services the agency offers.

What cuts could look like at local public health outposts

Already, state funding for the Georgia Department of Public Health trails behind its sibling agencies, the Department of Community Health, the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities, and the Department of Human Services.

DPH is slated to get around $435 million from Governor Brian Kemp’s budget in the upcoming fiscal year, a slight increase from the allocation for the current fiscal year. Most of that increase is due to the expansion of a home visiting program for new moms.

In comparison, DCH, the agency that oversees Medicaid programs for adults and kids, has about $5 billion in allocated funds, while DHS and DBHDD have north of $1 billion.

“And one thing that I would really emphasize about Department of Public Health, is it serves all 11 million Georgians,” said Leah Chan, director of health justice at the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute.

For example, DPH oversees restaurant inspections, issues safety permits to tattoo and beauty parlors, and investigates trends in deaths from drownings, overdoses, and suicides. Day to day, families and individuals can go to public health departments for services ranging from family planning to education on sexually transmitted diseases.

“There’s so many ways in which it really is providing a very unique set of services and functions that serve the entire state,” Chan said. “We don’t notice it until we need it, but it’s always operating there in the background.”

Having robust and consistent investments in public health is necessary to mitigate disaster, too, according to the latest recommendations from Trust for America’s Health, a nonprofit public health policy organization.

In the organization’s “Ready or Not 2025” report, Georgia’s public health system ranked among states with a high level of capability to respond to emergencies. Think of the ongoing measles outbreak, and highly pathogenic avian influenza, but also the opioid crisis, or heat waves, wildfires, hurricanes and other natural disasters.

Because of that slight increase to the Department of Public Health’s budget from the state, as well as success in other metrics, like the state’s plan for lab surges and participation in different accreditation programs, Matt McKillop, senior health policy analyst at Trust for America’s Health, said for now, Georgia is prepared.

“What we really want to make sure is that those investments aren’t being eroded over time,” McKillop said.

Particularly through funding cuts made to the CDC.

REALTED: Cuts to federally funded health care agencies drive outpour of support for affected workers

“It’s really drawing money away from state and local agencies who then either have to make up that funding on their own, which is often not going to be realistic given other state and local budget priorities and constraints, or they’ll have to make hard decisions about staff,” McKillop said.

Plus, Georgia does have some improvements to make. According to the Trust for America’s Health report, the state’s avoidable mortality rate, the average number of deaths in adults in kids caused by treatable or preventable conditions, is higher than the national average.

The report suggests that it’s also an indicator of gaps in health care access to treat chronic diseases.

McKillop warns that any cuts to spending on prevention, be it through programs to build up technology, lab capacities and who’s available to help on the ground, could cause a backslide.

“You spend millions to avoid spending billions,” McKillop said. “It’s worth engaging in those proactive investments to avoid being in a more reactive posture.”

In the Georgia Department of Public Health’s own strategic plan, which outlines goals through 2026, the agency recognizes its budget constraints. But it also proposes lowering costs for health care services to address maternal mortality, low immunization rates and deaths from drug overdoses. The plan indicates an expansion to its HIV prevention and treatment initiatives. At this point, it’s unclear what the agency will be able to accomplish on its list.

This article comes to Now Habersham in partnership with GPB News