(GA Recorder) — A tiny menace has been buzzing around Georgia’s coastal region and is trying to snatch up the state’s honeybees, but a team of scientists and state and federal employees are working to prevent the dangerous and disrespectful yellow-legged hornet from gaining a foothold in the Peach state.

The hornet, which can grow to about an inch long, was previously known as the Asian hornet, but two nests have so far been discovered near Savannah and destroyed by Georgia agriculture department staff and pest management professionals.

Adult yellow-legged hornets are vegans, living mostly off of sugars through nectar, but when they are young, they crave protein, and for that purpose, the adults have taken to hunting honeybees.

“Both the yellow-legged hornet and the giant hornet are somewhat unusual in that unlike most other wasps and hornets, which are kind of solitary hunters but all from one nest, the yellow-legged hornet and the northern giant hornet will both recruit their sisters once they’ve found the honeybee colony to go as a group and attack it, essentially,” said Lewis J. Bartlett, a professor at the University of Georgia’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences Entomology Department.

A hibernating queen hornet likely inadvertently hitched a ride on a boat that passed through the Savannah port. Scientists will work with the hornets’ DNA to determine how many generations have been born in Georgia, Bartlett said, but signs seem to point toward a recent arrival, which is good news for the effort to eradicate them.

In its native range, which includes much of mainland Asia from the Himalayas into southeast Asia, the hornets stalk outside honeybee nests, waiting to grab the fuzzy little friends and turn them into food for their carnivorous larvae. But Asian honeybees have developed some tricks to avoid that gruesome fate.

“There’s a hypothesis that has some evidence that the Asian honeybees, when they’re returning to the hive, which is where the yellow-legged hornets wait to intercept to them, that they essentially undertake these kind of aerial maneuver tactics, where when returning to the hive, they’ll kind of almost fighter pilot-style try to avoid the hornet,” Bartlett said.

Bees in other parts of the world haven’t developed those tactics, making them easy pickings for the hornets.

The black and yellow honeybee slayers have caused trouble in this way in other regions outside their normal habitat around the world, including in Japan, Korea, and parts of Europe.

Georgia Agriculture Commissioner Tyler Harper said his department will continue to hunt the bee-hunting bugs because if the hornets are able to become permanent Georgia residents, they could threaten honey production and native pollinators, which could be detrimental to farmers.

The honeybee is also not native to Georgia, but it’s widely beloved partly for the vital role it plays in supporting the state’s top industry and holds high honors as the state’s official insect.

“While this eradication is a win for our state and our agriculture industry, we’ll continue working around the clock to find any additional hornets, eradicate this invasive pest, and protect our state’s agriculture industry,” he said in a statement. “The public has played a vital role in this effort, and we’re asking Georgians to continue reporting any suspected sightings directly to the Department.”

Beekeepers on Georgia’s coast are taking that advice to heart, said Tim Davis, a beekeeper, director of the Coastal Georgia Botanical Garden and Chatham County Extension agricultural natural resources agent.

“Beekeepers are being vigilant, and they understand that this can be another new threat to an already difficult thing. Keeping bees is very difficult,” Davis said. “It’s not like it was when I was a kid, you put a hive out there and you get honey. You’ve got to be doing a lot of work, and this just adds that much more pressure to it, so they understand the importance of being out there looking for this.”

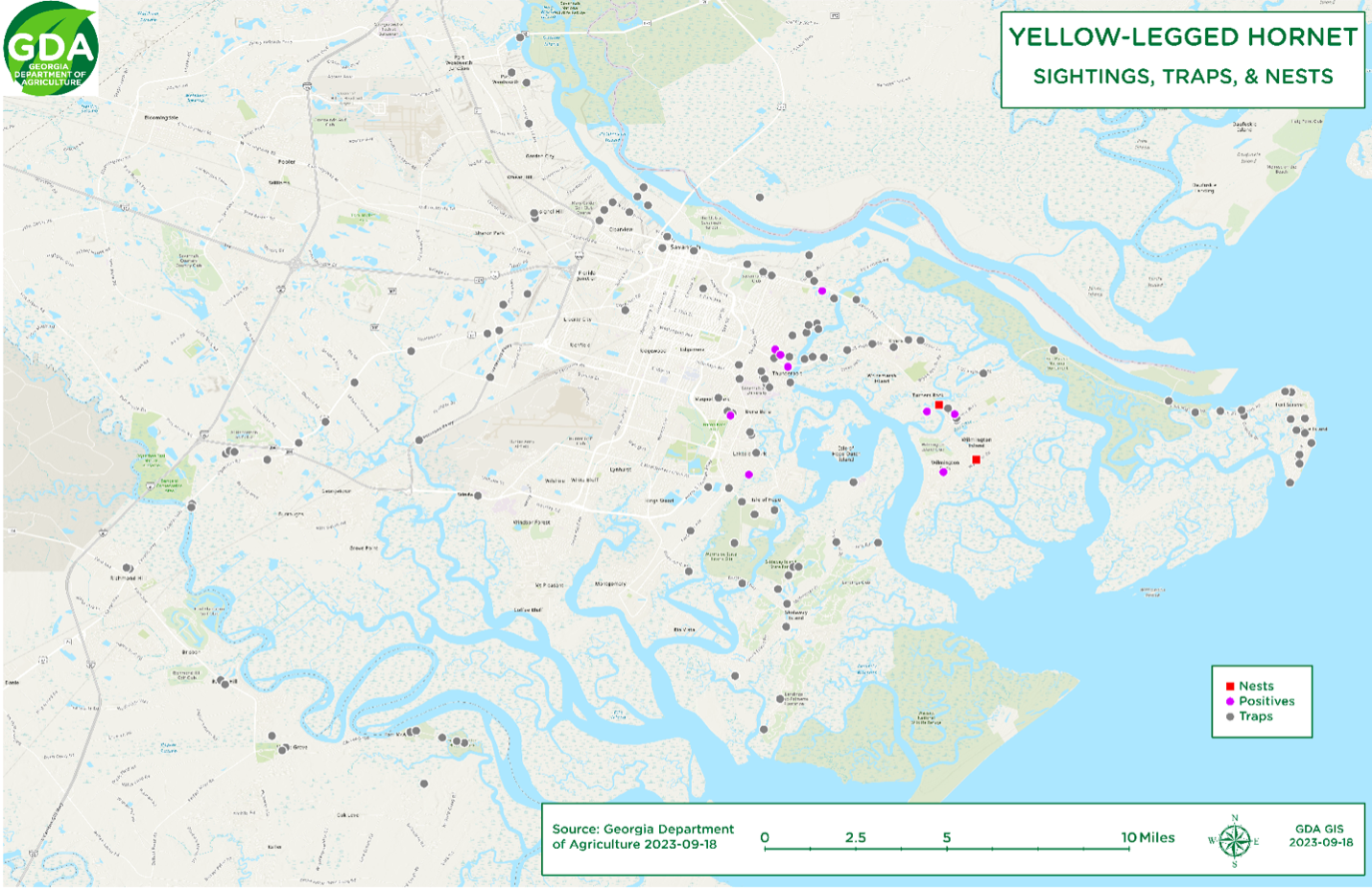

Davis said the state agriculture department has set up numerous traps, and some beekeepers and other bee-adoring humans are deploying their own homemade hornet traps.

“Basically, you can use a soda bottle, any plastic two-liter size bottle, and they cut holes of a certain size, and then you place bait in there and hang those in the shade of a tree somewhere near your bees, or anybody can do it, and then the hornets fly in and it’s a little harder for them to get out,” he said.

Since any hornets will be out hunting to feed their young this time of year, protein makes the best bait, and raw fish is the No. 1 choice, based on data from other places where the hornets have made themselves at home.

“They have some sweet baits, which are probably more effective earlier in the year than right now, so we’ve also looked at kind of combining those, making some of those baits from their recipes and adding some fish in there,” Davis said. “The fish works pretty well, although once it dries out, it’s not as attractive.”

Davis, who has spent his career working with invasive species like fire ants, said he is impressed with the cooperation between the state, the federal government and the University of Georgia and described himself as “cautiously optimistic” that their combined efforts will be successful.

“The key to that is always early detection and fast action, and I think we have early detection, and I think what GDA is doing, tracking and tracing and trying to find these nests is what we need to be doing right now,” he said.

Bartlett struck a similar tone, noting that Georgia experts have learned from other countries where the hornet has invaded and have the extra benefit of new technologies, including harmonic radar tags, which can be attached to a captured hornet and followed back to its nest.

“I actually rate our likelihood of containing and eradicating this as very achievable,” he said. “Because we have an army of essentially citizen scientists who are beekeepers, who are more than willing to put out traps, to alert us when one is spotted, and it’s a very densely populated area, and so we’re able then to deploy this community-based effort to find them, and then once we’ve found a worker, there’s many ways we can use that to find where the nest is.”