Macon Mayor Robert Reichert saw the rising number of people hospitalized for COVID-19 and went as far as he thought he could go with his mayoral pen: He issued an executive order “urging and pleading” residents to wear a face mask.

The order from the mayor of one of Georgia’s largest cities was issued Thursday even as the list of cities mandating facial coverings continued to grow. By Friday, more than a half dozen Georgia cities – including Savannah, Atlanta, Augusta and Athens – had ordered their residents to mask up in public spaces as COVID-19 numbers surge. More are expected to follow.

City officials who have issued face mask mandates, though, have crossed into murky legal territory. Their local edicts go a step further than Gov. Brians Kemp’s statewide order that “strongly encouraged” face masks. A spokeswoman for the governor called the local mandates – Atlanta’s in particular – “unenforceable.”

Reichert, who is also an attorney, said in an interview Friday that he might consider a more forceful order in Macon – if the governor officially says locals can mandate face masks. Today, he said he does not think he has the legal authority to issue such a mandate.

“Whether he relents and says, ‘OK, OK, I’ll either let the individual communities do a mandate or I’ll do a statewide mandate,’ I think he knows if he does a statewide mandate there are some areas of the state that might well go into rebellion over something like that,” he said. “They just feel that strongly about it.”

Reichert, who is a former Democratic state representative, said he tried to balance supporting the governor’s action with doing what he thought was best for his middle Georgia community – and what he thought would be the most effective.

“It’s difficult if not impossible to enforce,” he said of a mandate. “It creates a whole different set of problems to try to enforce it in situations that could ignite a powder keg on which we sit. It’s probably just as effective to implore, urge and plead with people to do the right thing as trying to mandate it.”

Other mayors see it differently – and so does Reichert’s own public health board. The board voted Friday afternoon to push the mayor and local commissioners to act next week to require face coverings for people are inside businesses and other facilities.

Ethel Cullinan, a member of the board who serves as a consumer advocate, said she thought it was worth wading into uncertain legal terrain.

“I doubt that anyone is going to say, ‘Well, I’m going to take you to court on this,’ but even if they did and even if we lost, by the time all that occurs, we will have saved lots and lots of lives,” Cullinan during Friday’s meeting.

‘Treacherous path’

The governor has so far let the local mandates take effect without a direct challenge, although he has leveraged criticism at Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms over her actions aimed at slowing the most recent flare-up of COVID-19.

“As clearly stated in my executive orders, no local action can be more or less restrictive, and that rule apples statewide,” Kemp tweeted after Bottoms announced plans to roll back some of the city’s reopening plans.

Kemp’s spokeswoman, Candice Broce, specifically called local mask mandates “unenforceable” and questioned whether cities were focused enough on enforcing the governor’s ban on large gatherings and restrictions on business operations.

“We continue to encourage Georgians to do the right thing and wear a mask voluntarily,” Broce said Thursday.

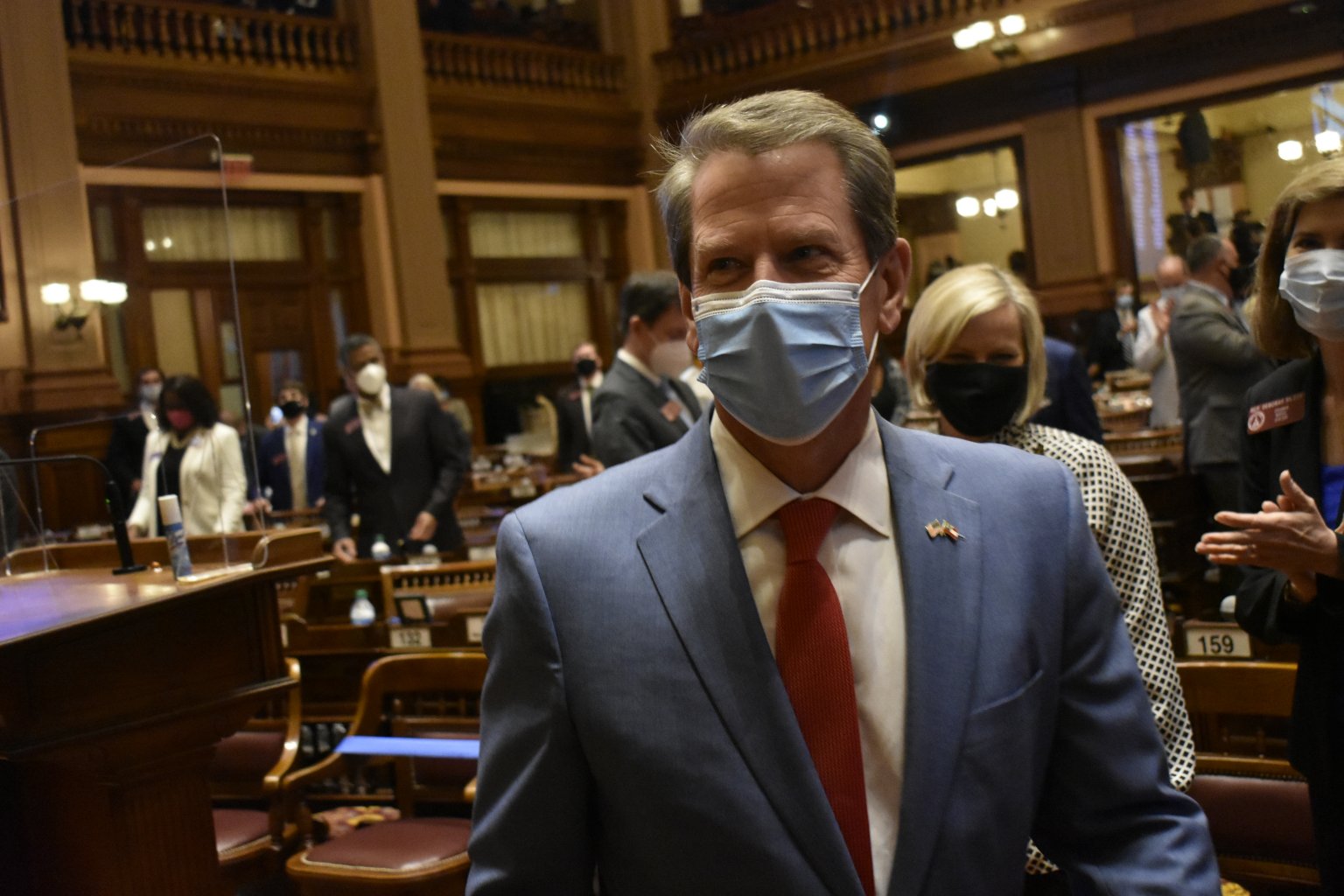

The governor recently tried to amplify that message across the state with a two-day “Wear a Mask” campaign, and he is often seen out in public wearing a mask. He has asked city and county officials not to mandate face coverings.

But there is a growing chorus of local officials who argue a public awareness campaign – and all the begging and pleading from officialdom – is not enough. Georgia has seen its daily COVID-19 numbers spike in recent weeks.

A mandatory face mask policy, they say, empowers local businesses and others to require their patrons come inside masked, and the city officials have tried to assure the governor that their mandates are in sync with his actions.

“I believe that you are genuinely concerned about the welfare of the entire state and all of her citizens and I believe that this emergency order complements your previous orders to keep our citizens safe during this extraordinary time,” Savannah Mayor Van Johnson wrote to the governor.

The Georgia Municipal Association has fielded a few dozen calls from city officials across Georgia since Savannah’s mayor issued Georgia’s first face mask mandate in late June, according to its General Counsel Rusi Patel.

The local leaders have been calling to inquire about their options as they weigh whether to impose stronger public safety measures than outlined in the governor’s executive order.

Patel said he advises city officials there is room for interpretation in state laws governing emergency powers, which were written to provide guidance when they need to respond to short-term disasters like hurricanes. Georgia is now past the three-month mark in a statewide response to an unprecedented public health crisis.

“Emergency management statutes haven’t been used to this extent before, either in length of time or the extent of the geography,” Patel said this week.

Patel said he expects other city officials who issue emergency orders to wear masks will use similar language to walk a line between where state and local authority appear to be in conflict.

“Local governments have police powers to protect the health, safety and welfare of the public,” Patel said. “We’re getting calls from city attorneys and elected officials who want to know what they can do to protect people.”

This spread of local face mask mandates is reminiscent of the early days of the pandemic, when cities and counties took actions that created a hodgepodge of restrictions intended to slow the spread of the virus, says Dr. Amy Steigerwalt, a professor of political science at Georgia State University.

Back then, Kemp eventually issued orders – including a statewide shelter-in-place order in April – that both scaled back local action in some areas and forced tougher restrictions in others.

The cities, she said, are now trying to thread a needle as they react to alarming increases in COVID-19 cases while trying to stay in bounds of the governor’s orders.

“I think they’re all very aware that the governor could sue and likely would win,” Steigerwalt said Friday. “The question is, does the governor really want to do that? Because that also is a really treacherous path.

“Do you want to – in the middle of a public health crisis where unfortunately, Georgia’s numbers are getting increasingly worse – sue places that are also having the sites of the outbreaks and say, ‘No, no, no, I’m not going to let you take the steps you think are necessary,’” she said.

Georgia Recorder Editor John McCosh contributed to this report.