WASHINGTON (States Newsroom) — Trump administration health officials announced Tuesday they hope to eliminate eight petroleum-based synthetic dyes from the nation’s food supply before the end of next year, though they haven’t received guarantees or written agreement from food companies.

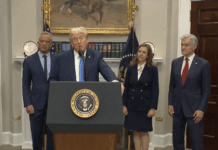

Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Marty Makary detailed efforts to phase out the dyes during a press conference alongside Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. at the department’s Washington, D.C., headquarters.

“Let’s be honest, taking petroleum-based food dyes out of the food supply is not a silver bullet that will instantly make America’s children healthy, but it is one important step,” Makary said.

The FDA’s proposal would revoke authorization for Citrus Red No. 2 and Orange B while setting up the agency to work “with industry to eliminate” Green No. 3, Red No. 40, Yellow No. 5, Yellow No. 6, Blue No. 1 and Blue No. 2.

FDA will also authorize new, natural food dyes in the months ahead.

Kennedy said the Trump administration has an “understanding,” but not an “agreement” with food companies that use the dyes, before deferring to Makary, who said that “you win more bees with honey than fire.”

“There are a number of tools at our disposal. And so I believe in love, and let’s start in a friendly way and see if we can do this without any statutory or regulatory changes,” Makary said. “But we are exploring every tool in the toolbox to make sure this gets done very quickly. And they want to do it. They want to do it.

“So why go down a complicated road with Congress when they want to do this? They don’t want to deal with the patchwork of 30 different state plans.”

Christopher Gindlesperger, senior vice president of public affairs and communications at the National Confectioners Association, released a written statement that didn’t appear to agree entirely with the FDA’s proposed phase-out, however.

“FDA and regulatory bodies around the world have deemed our products and ingredients safe, and we look forward to working with the Trump Administration and Congress on this issue,” Gindlesperger wrote. “We are in firm agreement that science-based evaluation of food additives will help eliminate consumer confusion and rebuild trust in our national food safety system.”

Removing additives

During the press conference, Makary held up watermelon, beet and carrot juices in clear containers, encouraging food companies to use those as dye, instead of the ones that may be removed from the market.

“We are simply asking American food companies to replace petroleum-based food dyes with natural ingredients for American children, just as they already do for children in other countries,” he said. “American children deserve good health.”

Makary said he believes there are several health conditions associated with petroleum-based synthetic dyes in food, including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, obesity, diabetes, insulin resistance, cancer, genomic disruption, gastrointestinal issues, and allergic reactions.

Kennedy said his goal as HHS secretary is to remove all additives in food served in schools “that we can legally address.”

The department, Kenedy said, will also work with Congress and President Donald Trump to increase labeling for food ingredients that Kennedy called addictive, including sugar.

“There’s things that we’ll never be able to eliminate, like sugar. And sugar is poison and Americans need to know that,” Kennedy said. “It is poisoning us. Is giving us a diabetes crisis.”

Health effects unclear

Martin Bucknavage, senior food safety extension associate at Penn State University, said during an interview with States Newsroom that petroleum-based synthetic food dyes are derived just to get the color.

“It’s not like it’s just a nasty chemical that they’re putting in there,” he said. “It’s something that’s been taken, it’s been chemically made, modified and then purified, so that it is just that chemical that provides that color. And then those colors have been studied.”

Similar to the complicated nature of nutrition studies — which can have a challenging time separating out a person’s genetics, exercise and environmental factors from one specific part of their diet — research on food dyes hasn’t been conclusive, Bucknavage said.

“In some cases, it does have an impact on hypersensitivity, but not in all cases,” he said. “And not all studies are basically showing the same thing. So there’s a lot of variability that exists out there.

“And I’m not saying, ‘Listen, we shouldn’t go through and study these things more and get better information on them.’ We certainly should. But again, it’s not an easy thing to do. Some of these studies take time and take a lot of money and sometimes the results are kind … more variable in terms of the results.”

States regulating dyes

The FDA’s announcement wasn’t the first time the federal government or state lawmakers have sought to ban food additives or synthetic dyes.

The Biden administration announced in January that the federal government would ban Red No. 3 in food beginning in 2027 and from medicines in 2028. Makary said during the press conference Tuesday the current administration plans to ask companies to phase out that dye sooner.

California lawmakers approved a bill in 2023 that will ban Red No. 3, propylparaben, brominated vegetable oil and potassium bromate from food starting in 2027.

The following year, legislators in the Golden State approved another measure that, starting in 2028, will ban six food dyes — Blue 1, Blue 2, Green 3, Red 40, Yellow 5 and Yellow 6 — from being sold in schools.

Those two state laws followed the California Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment releasing a report in 2021 that concluded “scientific literature indicates that synthetic food dyes can impact neurobehavior in some children.”

Virginia lawmakers approved legislation earlier this year that Gov. Glenn Youngkin signed in March to ban some artificial food dyes in public schools, starting in July 2027.

In deeply red West Virginia, Republican Gov. Patrick Morrisey signed a bill a few days later that will prevent seven artificial dyes from being sold in grocery stores starting in 2028 or included in school lunches starting in August.

Arizona and Utah have implemented laws of their own addressing food dyes.

The Environmental Working Group, an advocacy organization focused on strengthening health standards, reports that legislators in several states, including Arkansas, Florida, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Washington have introduced bills that could ban certain food dyes or chemicals.

Melanie Benesh, EWG vice president for government affairs, wrote in a statement about the FDA announcement that the federal agency “has known for decades that synthetic food dyes are linked to health problems, particularly in children, but has failed to act.”

“We’re pleased the administration is following the lead of states like California and West Virginia by finally announcing their intent to ban dyes,” Benesh wrote. “We’re grateful that states like California and West Virginia have forced the FDA to make food safety a bigger priority.”

Peter Lurie, president and executive director of the self-described food and health watchdog group Center for Science in the Public Interest, wrote in a statement released Monday that Americans “don’t need synthetic dyes in the food supply, and no one will be harmed by their absence.”

“The most important thing to know about food dyes is that their only purpose is to make food companies money,” Lurie wrote. “They are purely cosmetic, serving no nutritional function. In other words, food dyes help make ultra-processed foods more attractive, especially to children, often by masking the absence of a colorful ingredient, like fruit.”

Ashley Murray contributed to this report.