(States Newsroom) — More than 80 years after he died in the attack on Pearl Harbor, John Connolly was finally laid to rest – not as an unknown in a mass grave, but as a naval officer in Arlington National Cemetery.

When the Navy first called to tell his daughter, Virginia Harbison, that her father’s remains had been identified, she hung up. At 91, living in assisted care in Texas, she could hardly believe it. It was her son, Bill Ingram, who called her back to share the news again. She was silent for so long that he had to ask if she was alright. “Bill,” she said, “I hadn’t thought about that for 60 years.”

She has lived the full life her father never had the chance to. In March, Ingram pushed his mother in her wheelchair to her father’s gravesite for the burial.

“They fold the flag in this very tight, nice triangle, and then with white gloves, the commanding officer comes and takes it and kneels down and hands it to my mother,” said Ingram, who lives in San Francisco. “It was incredible.”

On Dec. 7, 1941, during the attack on Pearl Harbor, 429 service members aboard the USS Oklahoma died. Horrifyingly, men trapped below deck after the ship capsized could be heard tapping out “SOS” in Morse code as the air supply dwindled. Though 32 men were rescued, the rest were tragically not reached in time.

After the war ended, the remains were recovered and buried in the National Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii, too water damaged and commingled to be identified individually. There they remained for years until modern science caught up with historical tragedy.

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency disinterred the USS Oklahoma remains in 2015 to send to a DNA laboratory. Carrie LeGarde, a forensic archaeologist with the agency and project lead for the Oklahoma Project, said her team started the process by testing small pieces of bone for maternal line DNA. Overall, they inventoried 13,000 bones and took 4,900 DNA samples. For Connolly, identification was complicated.

“We had several sequences that had multiple individuals, and that was actually the case with John Connolly, and part of why his identification occurred later in the project,” she said.

Since John Connolly was older than most of the men aboard the USS Oklahoma, as one of the few officers on the ship and scheduled to retire just three weeks after the bombing, the team at DPAA relied on dental evidence in addition to DNA testing to confirm his identity.

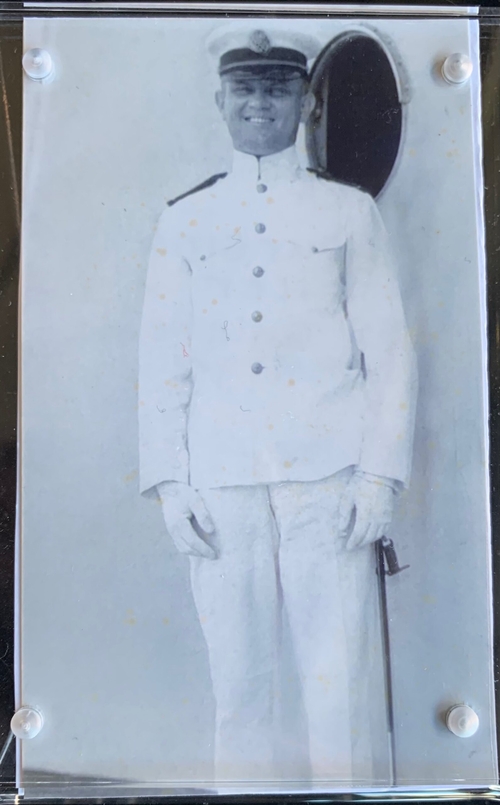

Connolly was born in Savannah in 1893 and joined the Navy in 1912. He served during World War I and was eventually promoted to a chief warrant officer. In 1941, his wife, Mary Connolly, and their two daughters, eight-year-old Virginia and six-year-old Helen, were eagerly awaiting his return and retirement in Long Beach, California, when the Navy informed them he had died.

Mary Connolly never remarried.

“She was very sad all her life because she married at age 30 or 31 and her husband was away in the service, but was killed right before he was supposed to retire,” Ingram said.

Connolly’s memory has been passed down through the generations.

“We’ve taken my family to Hawaii, and we went to the memorial and found the marker for his name,” Ingram said.

Everything changed last year when Ingram got a call from the Navy. In a 200-page report, the Navy detailed the historical background, identification process and scientific evidence.

“With the research that was involved, both with historical research and medical research, there’s a lot of folks at DPAA that are involved,” Navy POW/MIA branch head Richard Jenkins said. “We as a service will explain that to the family, with the hopes of them feeling comfortable with the findings and showing them that it’s not just any set of remains, it’s actually going to be that person.”

There’s a story that runs in Ingram’s family about his grandfather. A couple of years after World War II, a young man knocked on the family home and introduced himself to Virginia and Mary Connolly. He had been on the USS Oklahoma with John Connolly, he said, and when the ship was hit, Connolly pushed open a hatch and forced him out. Connolly had saved his life.

In 1944, the Navy re-commissioned one of their ships as the USS John Connolly. Though his story was a tragic one – an officer who never returned home whose remains were left unknown – history has granted him a second chance at closure. Over eight decades later, he got the hero’s burial he deserved.

“They did everything. They had a band. They played Taps. They fired the guns,” Ingram said. “Seven soldiers fired three times for a 21-gun salute.”

A final sendoff at last.