WASHINGTON (States Newsroom) — U.S. House Republicans adopted a budget resolution Thursday, clearing the way for both chambers of Congress to write a bill extending 2017 tax cuts and bolstering funding for border security and defense, though the blueprint set vastly different targets for spending cuts.

The cliffhanger 216-214 vote followed a tumultuous week on Capitol Hill. Far-right members of the GOP Conference said repeatedly they wouldn’t accept the outline, since it requires the House to write a bill that cuts spending by at least $1.5 trillion, while senators set themselves a floor of $4 billion in cuts.

Speaker Mike Johnson, R-La., was forced to postpone a floor vote on the budget resolution on Wednesday evening. But Johnson was able to secure the votes needed after he and Senate Majority Leader John Thune, R-S.D., announced Thursday morning that they were in agreement about meeting the higher threshold for spending cuts.

Johnson said both chambers of Congress “are committed to finding at least $1.5 trillion in savings for the American people, while also preserving our essential programs.”

“Many of us are going to aim much higher and find those savings because we believe they are there,” Johnson said. “We want to make the government more efficient, effective, and leaner for the American people. And I think that will serve every American of every party. And we’re happy to do that.”

Despite the difference in reconciliation instructions, Thune said the Senate is “aligned with the House” when it comes to cutting spending over the next decade.

“The speaker has talked about $1.5 trillion,” Thune said. “We have a lot of United States senators who believe that is a minimum.”

Thune added he believes it’s time for Congress “to get the country on a more sustainable fiscal path and that entails us taking a hard scrub of our government and figuring out where we can find those savings.”

Democrats, and some centrist Republicans, have expressed deep concerns the House’s instructions require the Energy and Commerce Committee, which oversees Medicaid, to cut at least $880 billion.

The panel, which also oversees Medicare and other programs, could not recoup that level of spending without pulling hundreds of billions from Medicaid, the state-federal program for lower-income Americans and some people with disabilities.

The budget resolution has been endorsed by President Donald Trump, who’s repeatedly urged the House to adopt the measure. “Great News! “The Big, Beautiful Bill” is coming along really well. Republicans are working together nicely. Biggest Tax Cuts in USA History!!! Getting close. DJT,” Trump posted on social media Thursday morning prior to the vote.

Only a beginning

The House adopting the 68-page budget resolution only marks the start of the months-long journey of writing and voting on the reconciliation package.

Republicans hope to use that bill to permanently extend the 2017 tax law, increase spending on border security and defense by hundreds of billions of dollars and rework energy policy.

The budget resolution includes different budget targets for many of those goals, and for raising the debt limit. It calls on the House to increase the country’s borrowing authority by $4 trillion, while the Senate’s instructions say that chamber would lift the debt ceiling by up to $5 trillion.

Writing the various elements of the reconciliation package will fall to 11 committee chairs in the House and 10 committee leaders in the Senate, as well as Johnson, Thune and a lot of staffers.

In the House, the Agriculture Committee needs to slice at least $230 billion; Education and Workforce must reduce spending by a minimum of $330 billion; Energy and Commerce needs to cut no less than $880 billion; Financial Services must find at least $1 billion in savings; Natural Resources has a minimum of $1 billion; Oversight and Government Reform has a floor of $50 billion; and the Transportation Committee needs to reduce deficits by $10 billion or more.

Four Senate committees — Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry; Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs; Energy and Natural Resources; and Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, or HELP — must each find at least $1 billion in spending cuts over the 10-year budget window.

House committees that can increase the federal deficit include the Armed Services Committee with a cap of $100 billion in new spending, Homeland Security with a $90 billion ceiling for new funding for programs it oversees, Judiciary with a maximum of $110 billion and Ways and Means, which can increase deficits up to $4.5 trillion for tax cuts.

Senate committees also got instructions for increasing the deficit, which will allow them to spend up to the dollar amount outlined in the budget resolution. Those committees include Armed Services at $150 billion; Commerce, Science and Transportation with $20 billion; Environment and Public Works at $1 billion; Finance with $1.5 trillion in new deficits, likely for tax cuts; Homeland Security at $175 billion and Judiciary with $175 billion.

The back story

If the process to reach agreement on a final reconciliation package is anything like the path to adopting the budget resolution, it will be long, winding and filled with drama.

The Senate voted for a completely different budget resolution in February that would have set up Congress to enact Republicans’ agenda in two reconciliation bills instead of one.

Budget Chairman Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., referred to the reconciliation instructions in that budget proposal as “Plan B.”

That tax-and-spending blueprint would have had lawmakers first write a bill increasing funding for border security and defense, and rewriting energy policy, before debating another bill later in the year to extend the 2017 tax law and cut federal spending.

The House voted about a week later to approve its original budget resolution, but not without a bit of theatrics.

Johnson didn’t originally have the votes and opted to recess the chamber before calling lawmakers back about 15 minutes later to approve that version of the budget resolution.

The Senate made changes to its reconciliation instructions in the House-approved budget resolution before voting to send it back across the Capitol for their colleagues to vote on final approval, which they did Thursday.

Politically difficult votes ahead

Each time the Senate voted on a budget resolution it undertook a marathon amendment voting session, known as a vote-a-rama, where lawmakers stay on the floor overnight to debate various aspects of the outline.

Senators will need to undertake one more of those when they debate the actual reconciliation package later this year, though the stakes will be much higher.

The budget resolution is a blueprint for how Congress wants to shape tax and spending policy during the 10-year budget window. It’s not a bill so it never becomes law. And it contains no actual money; it’s simply a plan for how lawmakers want to structure policy.

The reconciliation package, once written, will have the chance of becoming law, so any amendments offered during the Senate’s vote-a-rama will carry greater weight than the proposals voted on when the chamber took up the two budget resolutions.

Democrats will have an opportunity to challenge centrist GOP senators on whether they support or want to remove every single policy that Republicans put in their reconciliation package.

That could create real issues for GOP leadership if they include tax policy or spending cuts that cannot garner the backing of senators like Alaska’s Lisa Murkowski, Kentucky’s Mitch McConnell, Maine’s Susan Collins, and others.

The final reconciliation package will need support from nearly every Republican in Congress. GOP leaders will not be able to lose more than three House lawmakers or three Republican senators, under their very slender majorities.

Four or more Republicans opposing the reconciliation package in one chamber, either because it cuts too much spending or doesn’t cut enough, would likely prevent it from becoming law.

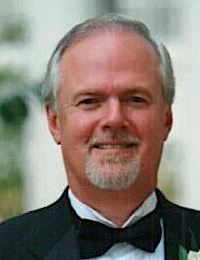

Thomas Strong Parrott left this earthly life to be in heaven with his true Father. He was born on November 23, 1950, in San Diego, California, and passed away unexpectedly in Gainesville, Georgia, with his best friends by his side, on the evening of April 7, 2025. Tom was an unforgettable man who impacted everything and everyone that he touched. Tom was brilliant, strong, funny, and passionate, and he loved the Lord with all of his heart. His children remember him for instilling in them a strong work ethic, a sense of humor, belief in God and Country, and being an example as a father. You would have felt his wisdom and humor if you knew him even for a minute. Tom asked for a few things with his passing, and the first is this… “Please don’t try and make me a saint in your memories. I want you to think of me as I was, a human being.”

Thomas Strong Parrott left this earthly life to be in heaven with his true Father. He was born on November 23, 1950, in San Diego, California, and passed away unexpectedly in Gainesville, Georgia, with his best friends by his side, on the evening of April 7, 2025. Tom was an unforgettable man who impacted everything and everyone that he touched. Tom was brilliant, strong, funny, and passionate, and he loved the Lord with all of his heart. His children remember him for instilling in them a strong work ethic, a sense of humor, belief in God and Country, and being an example as a father. You would have felt his wisdom and humor if you knew him even for a minute. Tom asked for a few things with his passing, and the first is this… “Please don’t try and make me a saint in your memories. I want you to think of me as I was, a human being.”

Bookman: Tariff chaos means pain for Georgia business – and maybe for state GOP in midterms

(Georgia Recorder) – Atlanta-based Delta Air Lines canceled earlier projections of record annual profits this week, with CEO Ed Bastian instead warning investors that the airline is canceling expansion plans and preparing for a recession.

“We’re in uncharted, unprecedented uncertainty when you look at what has happened,” Bastian said, calling it “a self-inflicted situation.”

“Until we get better clarity (from the Trump administration),” Bastian said, “I think our economy is going to continue to lose steam.”

The chaos in Washington and the carnage on Wall Street are also being felt in other ways in Georgia, with retirement accounts depleted, federal workers left jobless and companies large and small forced to reconsider business models that were designed for an economy that is being purposefully dismantled.

In early March, for example, the Georgia Port Authority announced another major expansion of its massive auto-import facility in Brunswick, which is already the second busiest in the nation. According to the GPA, one in 10 jobs in the area now depend upon the port, which is being expanded to store up to 1.4 million vehicles before they’re shipped to dealers inland.

When I drove by the port last week, a huge car carrier was unloading and the storage lots seemed full. That’s no surprise — foreign automakers have been rushing shipments to the United States in an attempt to get their product into the country before tariffs are imposed.

However, if Donald Trump’s economic plan has the impact on imports that he claims to want, those lots could be almost empty in a few weeks or months, and the expansion plan should be canceled.

If we do end up in a recession, it won’t be an accidental recession or the type of natural recession that comes at the end of a growth cycle. As Bastian noted, it will be a recession that Trump forced upon us with a nonsensical economic policy. And since his fellow Republicans have been too intimidated or infatuated by Trump to try to intercede, they too will own the political repercussions, which could be broad and deep.

Even before this upheaval, the 2026 election cycle seemed promising for Georgia Democrats. Mid-term elections tend to favor parties out of power, and a popular Republican governor, Brian Kemp, will be leaving office next year. And while Trump has shown the ability to draw casual voters to the polls when his name is on the ballot, he hasn’t been able to generate that same turnout from his base in mid-terms.

Take that situation, throw a recession on top of it and you have the makings of a transitional election in Georgia.

In short, if Democrats choose well, I think the stage is set for a 2026 election season in which Georgia elects its first Democratic governor in a generation, and perhaps other statewide officers as well. (The state Legislature is too well-gerrymandered to turn in a single election.)

The Democratic gubernatorial field has yet to take shape for ’26, but we already have a pretty good idea of what the GOP campaign will look like. In the primary, Attorney General Chris Carr, an ally of Kemp and someone viewed as a Trump skeptic by Republican standards, will be running against Lt. Gov. Burt Jones, a Trump supporter so avid that he served as a “fake elector” in 2020. Jones, a state senator at the time, also demanded that the state Legislature be called into special session to override Georgia voters and give the state to Trump.

Jones hopes to use Trump as a wedge in the 2026 primary campaign, reminding Republican voters that his support for the president has been absolute while Carr’s has been more situational. Given the ferocious loyalty of many GOP voters to Trump, maybe that will work, even if the economy turns sour, but in a general election it would likely be fatal.

Even if Carr wins the nomination, the GOP brand may be so toxic, and the party so divided, that a Republican victory becomes unlikely. But failure on the scale that we seem to be courting has to have its consequences.