ATLANTA (GA Recorder) — On Wednesday at 10 a.m., Georgia’s lawmakers are set to become mapmakers, gaveling in for a special session to redraw political boundary lines for a state on a metro-area growth surge as rural communities shed people.

Elected officials from both parties began drawing up map ideas long before the session’s start. But House and Senate Republicans both suddenly showed their visions for a territorial drift with an unveiling late Tuesday on the eve of the once-a-decade redistricting session.

The maps pit some longtime incumbents against each other, although some of the districts are open to new challengers. But lawmakers with jobs could be forced into a winner-take-all battle against a colleague to keep their seats, and if they are in the same party, whoever wins will create a net loss for their team.

Among Democrats, the map’s theoretical face-offs include Reps. David Dreyer of Atlanta and William Boddie of East Point, although Boddie is running for state labor commissioner; Reps. Rebecca Mitchell and Shelly Hutchinson of Snellville; Reps. Viola Davis and Billy Mitchell of Stone Mountain, who is chair of the House Democratic Caucus; Reps. Betsy Holland and Shea Roberts of Atlanta; Reps. Derek Mallow and Carl Wayne Gilliard of Savannah and Reps. Brian Prince and Mack Jackson of Augusta. Gilliard and Jackson both sit on the House Legislative Redistricting Committee.

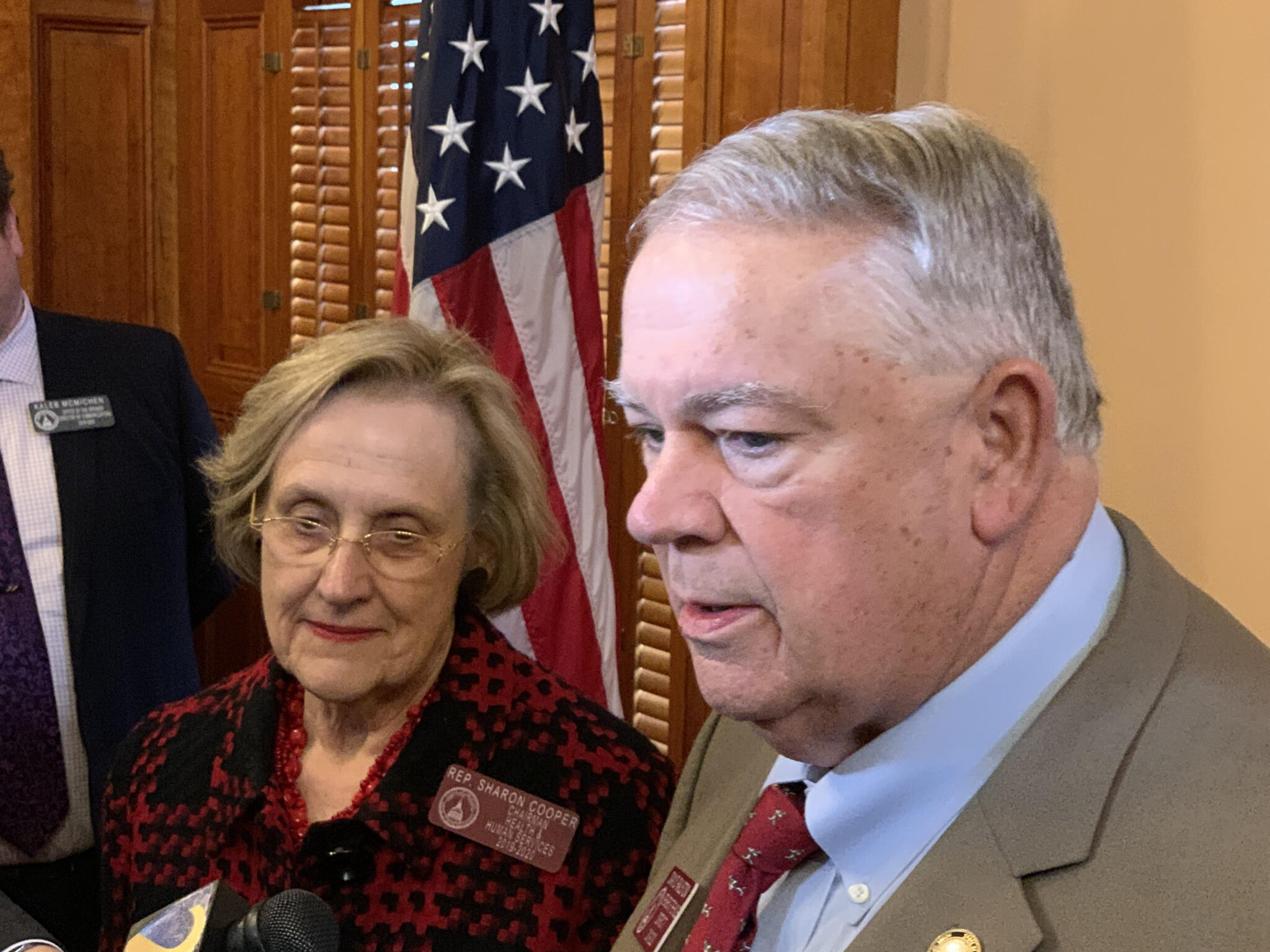

Republican incumbents drawn into competition with legislative colleagues include Reps. Sharon Cooper of Marietta and Matt Dollar of east Cobb; Reps. Brad Thomas of Holly Springs and Wes Cantrell of Woodstock, who has said he is not seeking another term; Reps. Bonnie Rich of Suwanee and David Clark of Buford – Rich is chair of the House Reapportionment Committee and Clark is not seeking re-election – and Reps. Emory Dunahoo of Gillsville and Tommy Benton of Jefferson, who was stripped of his leadership position last year after insulting the then-recently deceased Congressman John Lewis on a radio program.

Several lawmakers are proposed to be paired with members of the opposing party as well, including Lawrenceville Democrat Gregg Kennard drawn up against Lawrenceville Republican Timothy Barr and Albany Democrat Winfred Dukes pitted against Cuthbert Republican and longtime lawmaker Gerald Greene.

Dreyer said Boddie is not running for re-election so he can focus on the labor commissioner race, so they will not have to face off. But Dreyer puzzles why House Republicans would elongate his district as they did in the draft map.

“I live in House District 59, and already it stretches from the Plaza Theater to Hapeville,” he said. “And geographically, with Atlanta traffic, it’s difficult to get from both ends of the district in the same night if there are multiple community meetings. Under the new map, it runs from Memorial Drive close to Union City. So you’ve got folks in the City of Atlanta, East Point College Park and maybe even Union City under this new map. They have different priorities. It’s an honor to serve and I’ll do my best to represent every single person in the district I reside in, but these maps don’t keep communities of interest close together, which is one of the most important things any map should do.”

The proposed maps appear to divide Georgia communities into multiple districts, although House GOP leaders said overall five fewer counties would be split. For example, a southern portion of Glynn County, which is currently represented by Republican Reps. Buddy DeLoach and Don Hogan, would join the district of Republican Steven Sainz.

Residents at a Clarke County community hearing asked lawmakers not to split them up, but under the new plan, those voters would swap three representatives for four new ones. They are now represented by Republican Reps. Houston Gaines and Marcus Wiedower and Democrat Spencer Frye. If the plan passes and the lawmakers stay put, it would instead be split among Republicans Trey Rhodes, Barry Fleming and Jodi Lott as well as Democratic Rep. Henry Howard.

Georgia Senate plays opening hand

The Senate map released Friday suggests major lawmaker shuffling is in store for the suburbs north of Atlanta.

The district of Sen. Bruce Thompson, Republican of White, is moving south to north Fulton as Thompson runs for labor commissioner. The people living in what would become the new district are now represented by Republican Sens. John Albers and Kay Kirkpatrick and by Democratic Sen. Nan Orrock.

That move could cause a domino effect for northern metro Atlanta Senate districts. Albers would see his district stretch west to take in a slice of east Cobb and South Cherokee. Kirkpatrick’s east Cobb district which includes a piece of Sandy Springs would lose the suburban Atlanta city and instead stretch northward to Cherokee.

A Senate district at the south end of the state would leapfrog across hundreds of miles to north Georgia. Republican Sen. Tyler Harper of Ocilla is leaving the Senate to run for agriculture commissioner, and his south Georgia district is set to move to Gwinnett County, to an area now represented by Sen. Michelle Au, a Johns Creek Democrat. Au’s district would reach northward into Forsyth County, which leans more Republican.

Harper’s district, which now includes Ben Hill, Irwin, Coffee, Berrien, Atkinson, Bacon, Ware and Pierce counties, along with portions of Wilcox and Charlton, is slated to be absorbed by those of Republican Sens. Russ Goodman, Carden Summers, Blake Tillery and Sheila McNeill.

What to expect when you’re redistricting

For the legislators involved, the process will be akin to piecing together a massive, three-dimensional puzzle.

First, they need to meet legal requirements, ensuring that the state’s congressional and legislative districts are contiguous and contain roughly equal numbers of people.

They’ll also want to protect their power. Republicans control the governor’s office and both chambers of the Legislature, so they control the process and will want district lines that protect their majorities for another decade.

The GOP holds the majority in the House 103-77 in the General Assembly. Republicans have a 34-22 edge in the state Senate.

They want to set out to protect their political turf as rural communities continue to shed residents and as Republicans try to anticipate future demographic shifts that erode their advantage. The 2020 Census shows Georgians are increasingly moving away from rural areas, mostly in south Georgia, in favor of cities and suburbs.

“Those districts are going to be then reallocated into the Atlanta suburbs, and as they’re placed into the Atlanta suburbs, Republicans are going to make every effort to design them so that they’re likely to elect Republicans, at least in the short run,” said University of Georgia political science professor Charles Bullock. “The pain may be that in some of those rural areas – because so much of rural Georgia is now represented by Republicans – Republicans may be forced to pit two current Republicans against one another.”

Another priority will be to assign existing communities ranging from racial and language minorities protected by the Voting Rights Act to areas that represent major industries to smaller communities of interest like neighborhoods, school districts and churches, all of whom would prefer one legislator to turn to for assistance than two or three.

For Georgians, the results will determine who represents them in Washington and Atlanta for the next ten years.

“Redistricting is a foundational building block of democracy, it will determine not only the representation but the resources our communities receive for the next decade,” said Sen. Tonya Anderson, a Lithonia Democrat and chair of the Georgia Legislative Black Caucus. “Fair maps will ensure that all Georgians have a voice. Unfair maps will harm communities, some communities more than others, and in fact, gerrymandered maps that crack, pack and stack communities, like Black communities in Georgia, can be one of the most powerful forms of voter suppression.”

The special session will look much like a regular session except with masks and COVID-19 tests, but in Georgia, the legislative agenda will be limited to redistricting. The state constitution allows for the session to last 40 days unless extended by a three-fifths majority of both chambers, but lawmakers are likely to finish before Thanksgiving. The last redistricting session in 2011 lasted from Aug. 15 to Aug. 31.

“It’s a fairly streamlined process,” said Fair Districts Georgia Chair Ken Lawler. “A map gets introduced, let’s take the Senate map, the members of the Senate committee will address a proposed map, that will be addressed in the committee and voted on and it’ll go to the floor. The next day, they’ll vote on the floor, it’ll pass, it’ll go over to the other side. And next week, they’ll take it up.”

Anyone can draw a map, but only a lawmaker can propose it as a bill, and Republicans lead the redistricting committees, so maps created by Democrats or outside groups will almost certainly not gain traction.

There is little to stop Republicans from getting what they want out of the process, but what they want remains an open question.

They could choose to go all out and create bizarrely-shaped districts designed to preserve as much of an advantage as possible, as Democrats did in 2001, but a safer approach could be to play defense, shoring up districts they can’t afford to lose, thereby preserving a smaller but more easily defendable majority through 2030, Bullock said.

Once the maps are in play, individual lawmakers will likely propose amendments to their own districts, which remain to be hashed out.

“Sometimes it’s even a thing where a legislator will say, ‘Can we move the boundary over there so I’ll pick up my parents’ house? My momma wants to be able to vote for me,’” Bullock said. “Stuff like that happens.”

Both chambers generally defer to the other when it comes to creating their own boundaries, but the congressional map will get hashed out by both sides.

Once hammered out, the final product will head to Kemp’s desk. Once the governor signs off, the process will be complete, except for expected lawsuits.

This time when lawmakers draw new maps, they’ll do it under more vigilant watchful eyes of third-party groups like Fair Districts Georgia and a more engaged public. There are already signs of that increased interest, said Dr. Jennifer McCoy, a political science professor at Georgia State University.

A big reason for the increased attention is simply that the state has become more competitive after Republicans dominated Georgia elections for nearly two decades. Democrats, bolstered by the 2020 wins of President Joe Biden and Sens. Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff, argue Georgia voters are evenly split politically statewide and that the new maps should reflect that.

Heightened concerns about American democracy on both sides of the aisle are also bringing new attention to redistricting and other election-related processes.

“The citizens are starting to pay attention. This is something that’s in the weeds. People didn’t understand it. It’s complicated, it’s technical, and it hasn’t been very transparent. It’s been done behind closed doors,” McCoy said.

“So, I do think this is a positive outcome,” she said of the public’s interest in redistricting today. “And it does help to hold legislators accountable, but only sort of in the court of public opinion, not legally.”

Good government groups are also hoping the wider reach of technology will encourage more Georgians to pay attention this time around.

Fair Count Georgia announced on Tuesday a partnership with the Center for Urban Research at The City University of New York’s Graduate Center to create a website called Redistricting and You, which allows Georgians to find their current districts and quickly make comparisons with proposed new boundaries, including census and past voting data and a list of 300 community of interest maps provided by voters around the state.

Previously, Fair Districts Georgia teamed up with the Princeton Gerrymandering Project to create more than 1 million maps per legislative chamber and create an algorithm to weigh how gerrymandered new districts are.

Other proposed maps

Republicans led by Lt. Gov. Geoff Duncan released an early proposal of the state’s congressional lines last month. It has long been speculated that Republicans would try to unseat one of Georgia’s newest Democratic Representatives, Lucy McBath or Carolyn Bourdeaux, and Duncan’s early lines placed McBath on the hot seat. It removes from her district parts of Cobb County and adds parts of Fulton County and all of Forsyth County, changing it from 56-44 Biden in 2020 to 53-47 Trump, based on data from Redistricting and You.

Bourdeaux would fare much better under Duncan’s initial plan, going from 53% Biden to 62%. The Princeton Gerrymandering Project gave that map a C, saying that it gives Republicans an advantage in the state, but it could have been worse.

Democrats have countered with their own maps for Congress as well as the state House and Senate.

In Congress, Democrats propose a seven-seven split, which they say reflects last year’s close statewide vote between Biden and Trump and acknowledges the population shift toward metro Atlanta. Today, Georgia is represented by eight Republicans in Congress after Democrats flipped Bourdeaux’s district last year.

That map got an overall B from Princeton, with Cs in competitiveness and geographic splits.

Democrats overstate their advantage, Lawler said.

“The Democratic proposal for Congress says that we ought to have seven Republicans, seven Democratic, it’s a 50-50, right? That really leans too far to the left, our benchmarks say that’s too far,” he said. “We’re trying to use these benchmarks as the best independent test of what’s fair and what’s not fair. Even if we were a 50-50 state, therefore, we have seven and seven, it just doesn’t work that way because people live in clusters.”

The analysts gave the Democrats higher marks on their state House and Senate proposals, both of which would yield them some gains but keep the chambers under Republican control.

The data suggests those maps paint a more realistic picture of Georgia’s political climate, Lawler said.

“The Democratic Caucus Proposal for state Senate shows 25 Democrats, 31 Republicans,” Lawler said. “And we actually think that’s fair. That matches the natural political distribution of voters in Georgia right now. It’s within the range.”

Lawsuits on the horizon

But the process seems much more likely to end in a courtroom rather than with interparty high-fiving.

And the Democrats are likely calculating that by playing nice with their proposed maps early in the process, thinking that could give them an advantage if the final maps end up in front of a judge.

“The strategy for the minority party is, by offering alternatives, if they then go to court, which almost always happens in redistricting, then they can build their argument as to why they’re challenging the state’s map,” Bullock said. “They can say, ‘Here, we did this alternative,’ which Democrats would argue is much fairer, say, to a minority group or something like that. The court wouldn’t just unilaterally substitute the plaintiffs’ map, but it would be a basis that the court could point to a question about, ‘Well, did the Legislature consider this alternative? Why didn’t it adopt it?’ They’ll be trying to build a record.”

If a lawsuit comes, it will likely center around race.

This is the first redistricting and reapportionment since the 2013 U.S. Supreme Court ruling struck down the preclearance requirement in the Voting Rights Act. A decade ago, Georgia’s maps had to win the approval of the Justice Department in Washington; today, they do not.

The Voting Rights Act still allows an opportunity for legal challenges claiming new district lines are racially discriminatory.

“Other than that, there’s really no other oversight, particularly in a state like this one that has a trifecta, where one party controls the three branches,” McCoy said.

If members of a racial or language minority believe their vote has been diluted by the new maps, whether by being packed into a small number of districts or cracked up into multiple districts where they have little say in elections, they could have cause for a lawsuit against the plan.

That could mean more hurdles to clear for lawmakers looking to balance population levels, historic voting patterns and existing communities of interest.

“One of the things which may be a challenge would be to try to maintain the level of Black concentrations in some of the underpopulated districts,” Bullock said. “The most underpopulated districts tend to be ones that are currently represented by African Americans. And it may be that in some of those instances, it will be challenging to keep the Black percentage as high as it currently is. If you have to bring in large numbers of new people to get the population up to one person, one vote, can you do that and maintain the same level of concentration?”

Georgia Recorder Deputy Editor Jill Nolin contributed to this report.