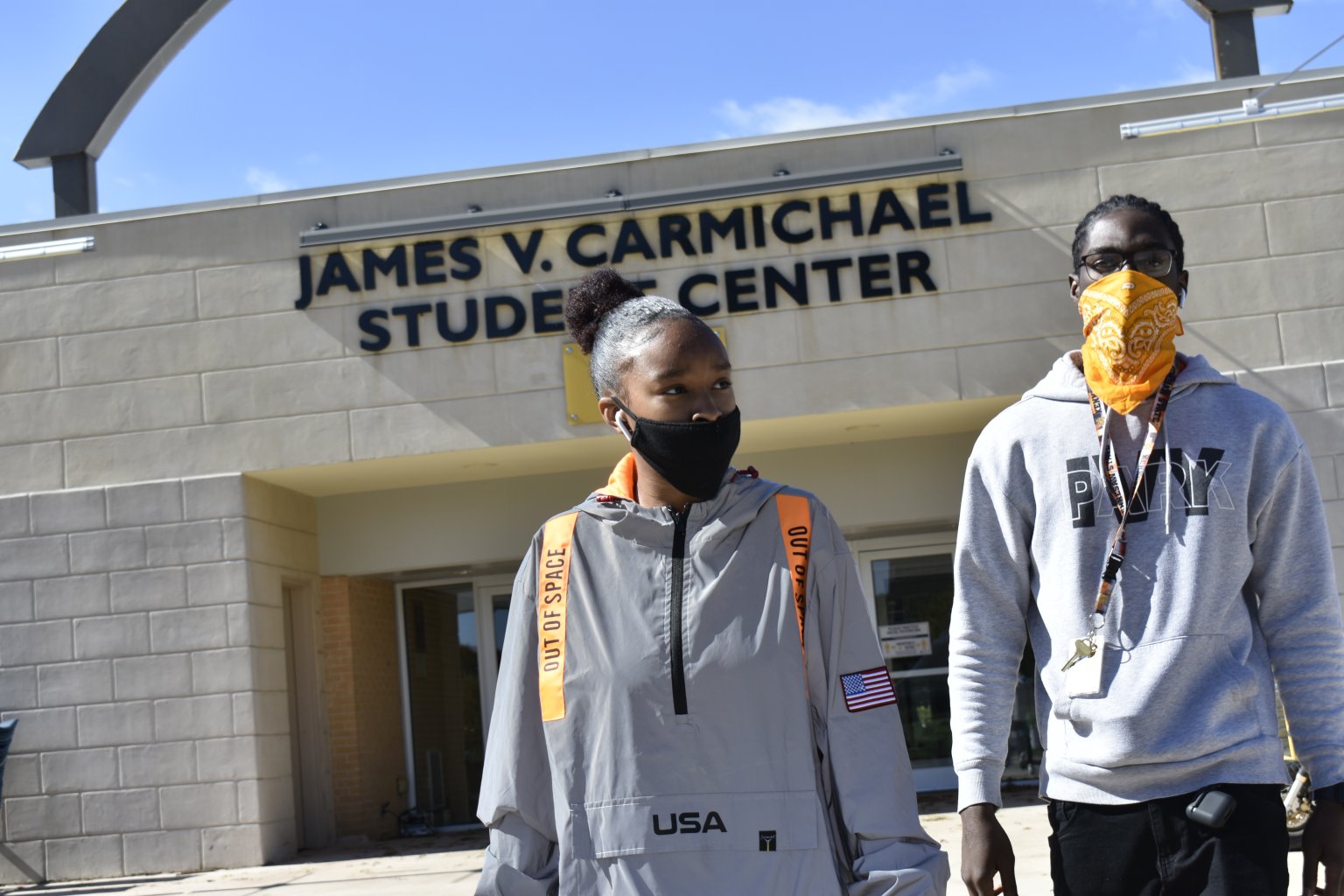

A fall semester rife with pandemic anxiety and online lessons on Georgia’s college campuses is coming to a close and school officials are preparing for students to spend more time together in a classroom next semester.

The University of Georgia’s English department is working to nail down classrooms to accommodate 100% of social-distanced freshman writing classes, according to an email sent last week to instructors from Nate Kreuter, associate professor and director of first-year writing.

Half of the students in those classes, some of the largest on campus, will be studying in-person at any given time, with the other half attending via Zoom, Kreuter said.

“I realize that these are big changes for some of you, depending on how you’ve been teaching this fall, and emphasize that these changes come at the request of the (Office of the Vice President for Instruction) and Franklin College,” he wrote. “They are concerned, as am I, that many of our first-year students are falling through the cracks and failing to build the social and intellectual relationships that are necessary for successful degree completion.”

The change comes as the Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia is pledging to “maximize safe in-person instruction” and “ensure hybrid instruction includes a vast majority of in-person interactive instruction where appropriate and safe,” according to a resolution passed by the regents Oct.13.

That sounds good to Nicole Johnson of Oconee County, the mother of a daughter who is a senior at the University of Georgia and a son who is a freshman at Kennesaw State University. Johnson is an administrator for a Facebook group with more than 5,000 members dedicated to keeping Georgia’s universities open.

Johnson’s son has learning disabilities that made the abrupt end to his high school career difficult when Gov. Brian Kemp closed schools to in-person instruction in March to slow the spread of COVID-19.

“For students with disabilities, online learning is not just not ideal, for some kids, it’s no deal,” she said. “There is no school, if you don’t have support that you need, and so for him, he had been out of school since March. We were desperate for school to start, and for him to have a focus and a goal and something to do and somebody to socialize with. So for us, it was a no-brainer, he was going to the dorm if the dorm was open, and thankfully, Kennesaw did open and we moved him in and he has a roommate, and it’s not ideal, but it’s much better than being at home and trying to learn online.”

Johnson said her son registered for classes with a schedule including four in-person classes and one online class, but last minute changes meant he ended up going to one in-person class per week and doing the rest of his work online from his dorm. It’s not the college life either of them envisioned, but it’s better than nothing, and they understand it has not been easy for universities to operate with so many new variables, Johnson said.

Parents and students in Johnson’s Facebook group worry about the toll isolation is taking, citing reports of increasing mental health challenges among young people associated with the pandemic lockdown. Others balk at paying expensive tuition rates, room and board and campus fees but receiving an inferior level of instruction.

Johnson said she and her family are feeling positive about the upcoming semester, provided her son’s schedule does not change again. A meeting with University System of Georgia Chancellor Steve Wrigley left her feeling better about the spring. Wrigley urged schools to get back to the classroom as much as possible early in fall semester, even as school faculty and staff resisted for fear of contracting COVID-19.

“He said that the Board of Regents (is) encouraging the schools to provide more face-to-face classes and interactions with students, to the extent possible,” she said.

Many Georgia university students are feeling less than optimistic about the upcoming semester.

Jessica DeMarco-Jacobson is a junior at Columbus State University and senior copy editor at the university newspaper, the Saber.

“I’ve been very concerned about going back in-person when the pandemic doesn’t seem to be improving, and I tried to go with the online or hybrid options as much as I could,” she said. “I have immunocompromised family members, and I just don’t think it’s safe, period, even if that wasn’t the case. I think it’s very worrying, especially because CSU doesn’t do testing at the school, it’s all self-reported.”

Protocols for testing, reporting and isolating cases vary among the university system of Georgia’s 26 institutions. Columbus State University students are advised to seek testing through the Georgia Department of Public Health, which has a partnership with the university. The Georgia Institute of Technology offers walk-up on-campus testing and surveillance testing of asymptomatic students, faculty and staff.

DeMarco-Jacobson can count on one hand the times she’s visited campus this semester, but she will not be able to avoid in-person classes in the spring. She had to schedule two in-person classes starting in January, despite her fears of spreading the virus.

“If the school is pushing for more in-person, I think there’s going to be bigger crowds on campus, and I’m really scared, to be honest,” she said.

Even though she would rather stay away from those crowds, online classes come with their own challenges, she said.

Some students are struggling to stay motivated, and others are feeling depressed, she said. Even though her classes are online, many are sparsely attended.

“So for example, it’s just me, and three or four other people who will show up for discussion,” said DeMarco-Jacobson, an English literature major. “It’s the same people coming every time, and for another class that has optional meetings, it’s like me and one other person. And sometimes I just kind of lose the motivation to show up, to be honest, because I love discussing books, that’s why I got into my major, and it’s just difficult to have that same discussion when it’s only like, four people.”

Some professors say they do not yet know what the regents’ push to promote in-person instruction will mean for them.

Matthew Boedy, a University of North Georgia associate professor of rhetoric and composition and conference president of the Georgia chapter of the American Association of University Professors, said one of his biggest questions is what hybrid classes will look like next semester.

Boedy said he has been told the new expectations are that all hybrid courses will meet 50% face-to-face or once per week at minimum.

“There have been classes where you would meet once a month or every couple of weeks,” Boedy said. “I was doing basically every three or four weeks, depending on the class, and now, I have to do 50%, which, of course, I’m not going to do that.”

The regents’ resolution might lack details, but it is sending a clear enough message that school administrators are firming up plans to get students seated back on campus.

“It’s very unclear how it’s going to be implemented,” said University of Georgia math professor Joseph Fu. “The regents’ resolution reads as sort of a statement of principle, and I think it comes with an implied urgency, perhaps an implied threat. These resolutions tend to fall in line pretty quickly, and I guess the news about the English classes is the first concrete expression of that at UGA.”

Fu has been an outspoken critic of the university’s pandemic response, which he said ignores the interests of faculty, staff and students. Cases of the coronavirus spiked in some of Georgia’s university towns and faculty and staff at UGA held a “die-in” early in fall semester in response to the pressure to work on campus.

A recent survey sent to UGA students asked about their mental health and how they are doing in online classes but did not collect data about their thoughts on the virus, Fu said.

Fu said he understands the concerns of parents like Johnson, but thinks administrators are putting those concerns above the safety of faculty, staff and students.

Fu and others say they believe the regents’ push to reopen is based on finances, with many pointing to correspondence between the university system and dormitory operator Corvias in which the company urged the board not to adopt restrictions on dorm occupancy.

“I think these parents have a point, face-to-face learning, classroom learning is better for everybody,” he said. “It would be easier for me, it’d be easier for my colleagues if we did it, but it has to be safe. ”

This article appears in partnership with Georgia Recorder