WASHINGTON (GA Recorder) — The White House and a bipartisan group of U.S. senators said Thursday they’ve struck a deal on the outlines of a $1.2 trillion infrastructure package, marking a breakthrough on federal dollars for road and bridge projects after weeks of negotiations—but with significant hurdles still ahead.

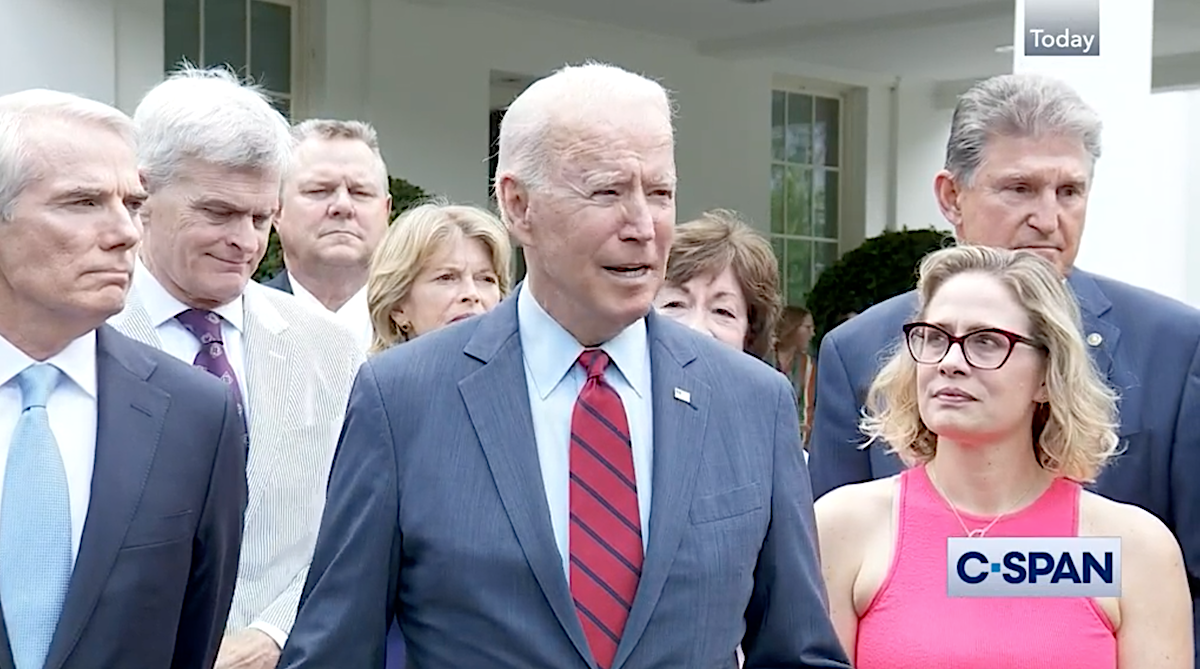

President Joe Biden stood with the 10 senators involved in those talks, led by Arizona Democrat Kyrsten Sinema and Ohio Republican Rob Portman, as they announced the agreement to reporters outside the White House. Biden heralded that legislative framework as the result of trust and compromise between himself and those lawmakers.

“None of us got all that we wanted. I didn’t get all that I wanted,” Biden said. “But this reminds me of the days we used to get an awful lot done up in the United States Congress.”

The key senators involved in the infrastructure talks besides Sinema and Portman included Republicans Bill Cassidy of Louisiana and Susan Collins of Maine; and Democrats Jeanne Shaheen of New Hampshire; Jon Tester of Montana; and Mark Warner of Virginia.

The announcement of the deal is a critical step, but the arrival of an actual bill on Biden’s desk remains in the distance. Progressive Democrats are adamant that it be accompanied by a second piece of legislation containing “human infrastructure” that Republicans had opposed, like in-home care services for older Americans and those with disabilities.

The size of the roads-and-bridges infrastructure package is also considerably smaller than the $2.3 trillion, wide-ranging proposal that Biden initially proposed.

But as he was championing the bipartisan infrastructure agreement, Biden said congressional Democrats will be moving “in tandem” to advance those other human services proposals boosting public funding for caregiving, child care, education, and other social policies that he has described as critical to the modern U.S. economy.

He said those aspects are “inextricably intertwined,” and cautioned that he will not sign the bipartisan bill if the other policies aren’t also sent for his signature.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said earlier Thursday that the U.S. House will not take action on the Senate’s bipartisan bill until the Senate has taken up both proposals.

The second portion will require Democrats to again use a process called reconciliation, which will allow them to pass legislation without any votes from Republicans in the evenly divided Senate. Both chambers also will have to agree on a budget resolution.

“Make sure you understand this: that when people say, ‘Well, I’m not going to vote for this unless I see that,’ there ain’t gonna be no bipartisan bill unless we are going to have the reconciliation bill,” Pelosi said.

An outline of the new bipartisan agreement released by the White House says it would spend $1.2 trillion over eight years, with $579 billion from new spending.

The White House fact sheet listed some details of the existing federal dollars that would be repurposed, but not precise dollar figures.

Among the potential funding sources included were unused unemployment relief funds; unused money from last year’s COVID-19 relief bills; and public-private partnerships.

It also mentioned but did not offer additional details on potential state and local investments in broadband infrastructure, and allowing states to sell or purchase unused toll credits.

Biden said the bipartisan agreement would make “significant down payments” on overdue federal spending in a number of areas, including the largest investment in public transit funding in U.S. history and the most money for rail projects since Amtrak was created.

It also would include $15 billion for electric vehicles and charging stations, money to improve water storage in the drought-challenged West, and $47 billion for “resilience” programs — which Sen. Bill Cassidy, (R-La.), praised as critical for coastal states dealing with climate-change challenges.

It would not increase the federal tax on gasoline, or charge a new fee on electric vehicles that don’t pay the traditional gas tax, he noted.

After negotiations that have taken weeks to agree on the financial scale of a potential bill and the definition of what exactly gets to be called infrastructure, senators involved in those discussions heralded the ability to reach a deal as much as its contents.

“We’ve agreed on the price tag, the scope, and how to pay for it,” said Sen. Susan Collins, (R-Maine.) “It was not easy to get agreement on all three, but it was essential. It was essential to show the American people that the Senate can function, that we can work in a bipartisan way.”

Sinema said the agreement “shows that when a group of people who are committed with shared values to solving the problems and challenges our country faces, we can use bipartisanship to solve these challenges.”

“It meets the needs of folks who live from Virginia out to Arizona,” said Sinema, who with Portman flanked Biden at the announcement on the White House driveway. “It invests in green energy and climate, recognizing the changing nature of our country and our future.”

Portman praised the package for eliminating “non-infrastructure items,” not relying on new taxes, and for “a commitment from Republicans and Democrats alike that we’re going to get this across the finish line.”