In the 1960s, the Apollo astronauts used three man-made marks on the planet to navigate from space . . . the Great Wall of China, the pyramids of Egypt, and the Copper Basin in Tennessee/Georgia. According to the TVA, that was even after 30 years of replanting trees in the basin in an attempt to reclaim the land. But let’s not get ahead of the story.

Once upon a time, there was a beautiful area about 50 miles wide and 50 miles long that covered the eastern corner of Tennessee, part of western North Carolina, and some of the northern mountains of Georgia. The forests were dense and beautiful. Fast-moving streams and the Toccoa/Ocoee River moved through the area. Fishing was outstanding. The Cherokee had lived, hunted, and thrived there. It must have been as beautiful as any place we see today in the North Georgia and Tennessee mountains.

Once upon a time, Mr. Lemmons, a prospector panning for gold in a small stream just off Potato Creek, thought he had found the mother lode. Instead, he had discovered copper ore. His discovery changed the history of that area forever. The year was 1843. Interestingly, evidence found in 1880 suggests that the Cherokees were mining and using the copper long before the miner’s discovery in 1843.

Once upon a time . . .

From beautiful to desolate beauty

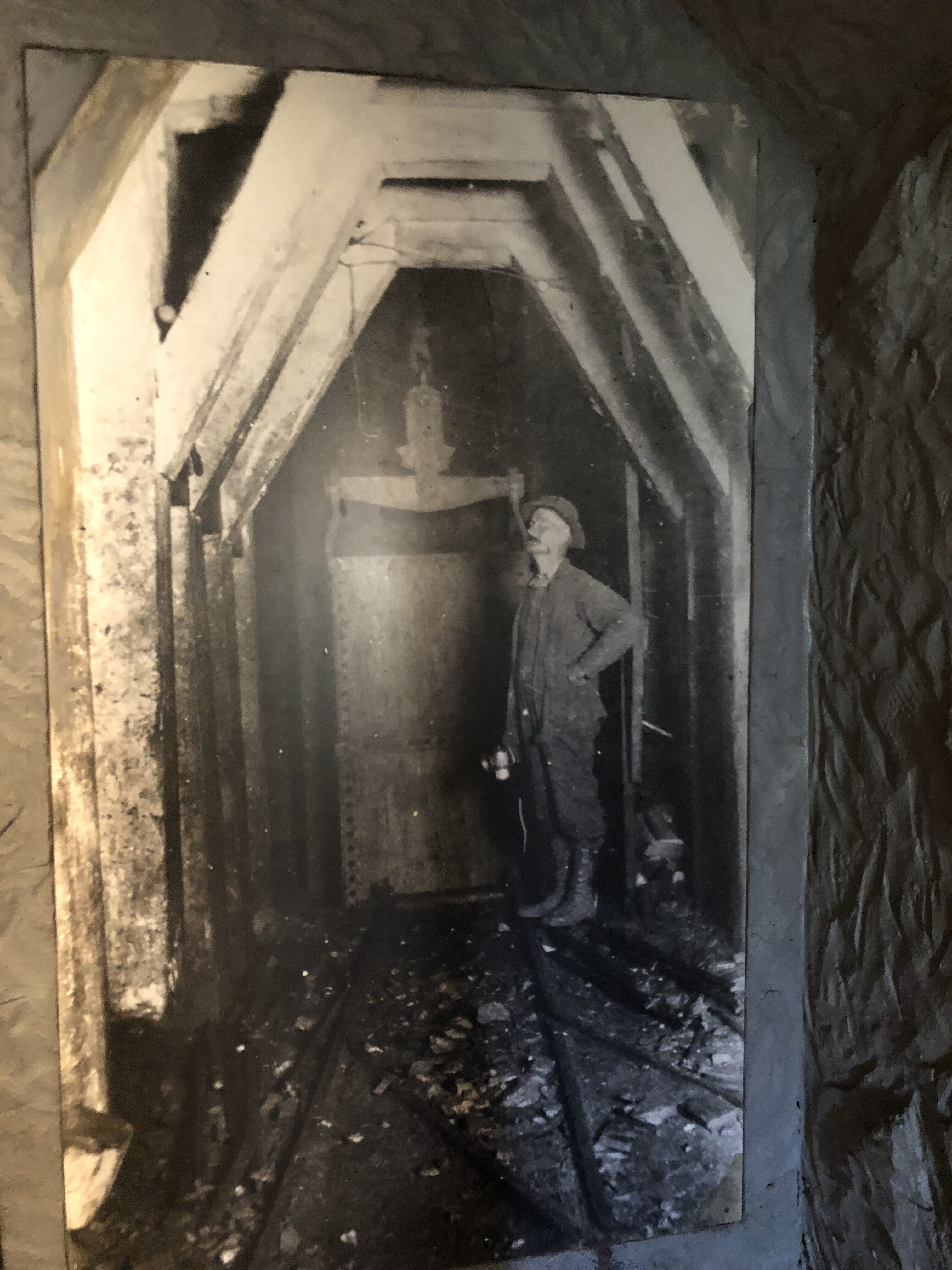

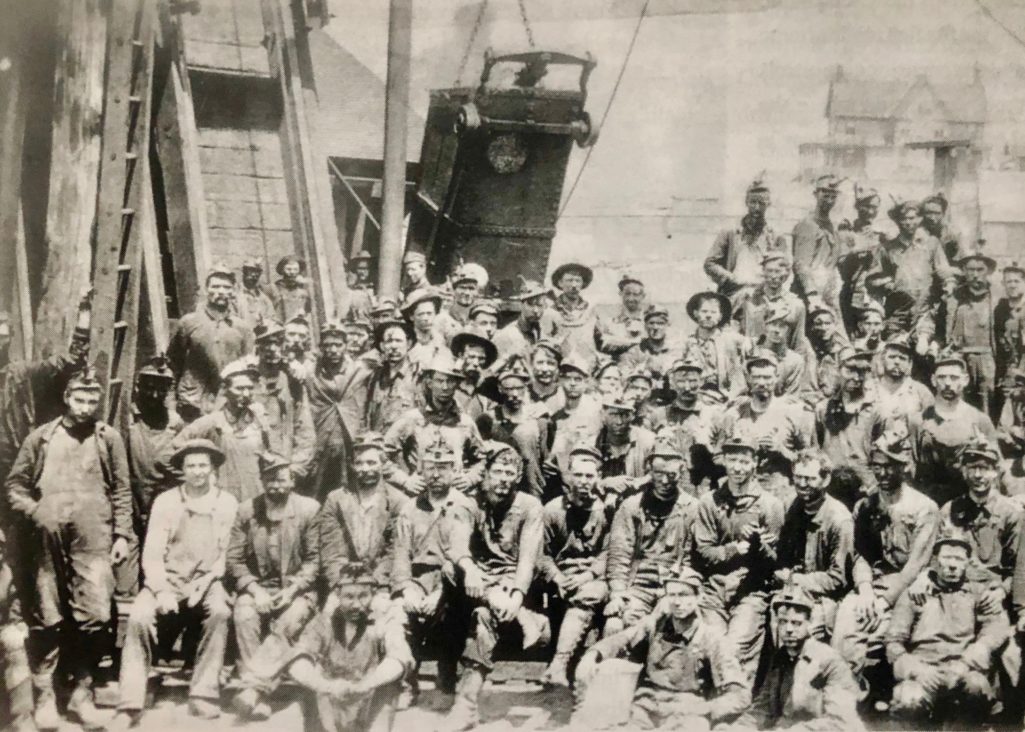

Copper was a valuable commodity in the mid-1800s, and miners and mining companies flocked to the area that became known as the Copper Basin (a.k.a. Ducktown Basin). The miners used picks, shovels, and man-powered drills to dig out the ore. Over time, the miners followed the copper veins deep underground. What they brought out of the earth was an ore mixed with both high-quality copper and low-quality iron. At its prime, more than 12 mines were established, working independently to get as much copper out of the ground as possible.

Preparing the copper ore the miners dug out to be sold was a five-step process. First, the copper and iron ores were separated from the sulfur. The ore was smelted in a process that was new at the time called the open roast heap smelting process. The ore was roasted on large piles of wood for up to three months. During that time, the iron and the copper ore were separated from sulfur dioxide that was turned into gas. The sulfur gases settled on the vegetation, killing everything it touched and in the waters, killing fish and poisoning the water. Rainwater washed away all of the topsoil. According to AppalachianHistory.net, “The nation was getting its first look at the long-term effects of acid rain.”

Other steps were needed to separate the copper from the iron. By the late 1800s, all the trees in a 40-square mile area had been cut down and used in roasting. All that remained were the red clay hills and valleys. The area looked like a wasteland.

Even worse, sulfuric smoke from the fires continually hung over the basin. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) described the smoke as an eternal fog that was too thick to see through. “Mules wore bells to keep from running into one another.”

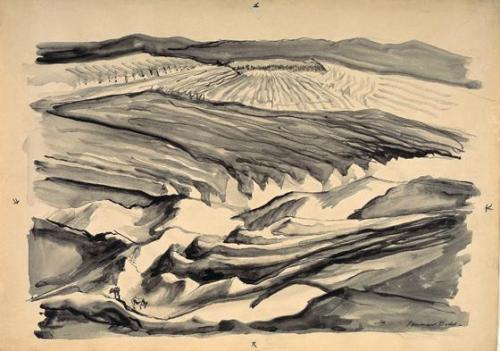

According to the museum exhibits that are there now, the area was given “the scientific designation of ‘Ducktown Desert.’ Eventually, over 50 square miles of land was ravaged, or damaged to varying degrees.” Interestingly, there were those who saw beauty in the scarred landscape. World-renowned Georgia artist Lamar Dodd visited the area several times to paint the landscape. He was drawn to “the variety of color and shapes” there. Those who grew up in the area also saw beauty in the destruction. Most had never seen the area covered with plants and trees and, instead, loved the stark red hills and the “desolate beauty” of the area.

Reclaiming the land

Because of the damage to the land and the water systems in the area, the TVA took on the task of helping reclaim the land. When the TVA first showed up in the 1930s, shortly after its creation, the destruction of the land had been going on for 90 years and looked to be irreversible. Over 23,000 acres of land had been ruined through the mining process and reduced to red clay.

Over the next 70 years, the TVA planted trees -–millions of them. Bulldozers were used to break up the top two feet of clay and treat the land with lime. Helicopters were used to treat the soil with fertilizers, and seeds were spread over the area. Crews planted trees by hand.

The reclamation process didn’t happen over time. It took over 70 years and more than 16 million trees planted to restore the forests, reclaim the integrity of the water systems, and see the environment become healthy again.

Why visit Copper Basin

Today, the area’s top asset is tourism as people return to fish and raft the streams and rivers, shop for apples, and enjoy the mountain air. In the restoration process, 1,000 acres were left alone so visitors could see the severe damage the mining did to the land. And a museum has been created to allow visitors to see the historical story of the area.

My husband, Bob, and I took our 16-year-old grandson Nate up there to visit. Nate has considered becoming an engineer, and we thought visiting an area that had been so devastated by bad decisions and lack of long-term planning could be interesting to him. Our son, Scott, told us that if Nate took photos while there, we would know that he had become really involved in the story. We were thrilled with his interest, his questions, and his observations.

As has been often said, “If we don’t learn from history, we are destined to repeat it.” For the next generations, it’s important that they consider what it means to be caretakers of the land to preserve it for generations to come.

All the details

The names Copper Basin and Ducktown Basin are used interchangeably. Coppertown, Georgia, and Ducktown, Tennessee, are on either side of their state boundaries. The dividing line is along the Main Street that separates the two towns.

The Ducktown Basin Museum is located at 212 Burra Burra Street, Ducktown, Tennessee, 37326. Admission is $5 for Adults; $4 for Seniors; $2 for ages 13 to 17; and $1 for ages 12 and under. Hours vary by season. Check the website for updated hours.

The museum includes an interesting video, exhibits, and historical artifacts. Outside the museum is a walking trail with exhibits of copper ore and mining equipment along the way. The visit can take about an hour, or longer if you like to read everything.

An added attraction is the opportunity to visit the mineral collecting area behind the museum. The area contains three dump-truck loads of ore that came from the ore bins at the Central Shaft. The cost is $12 per person. The museum does not provide any tools or supplies for collecting. Visitors must bring their own.