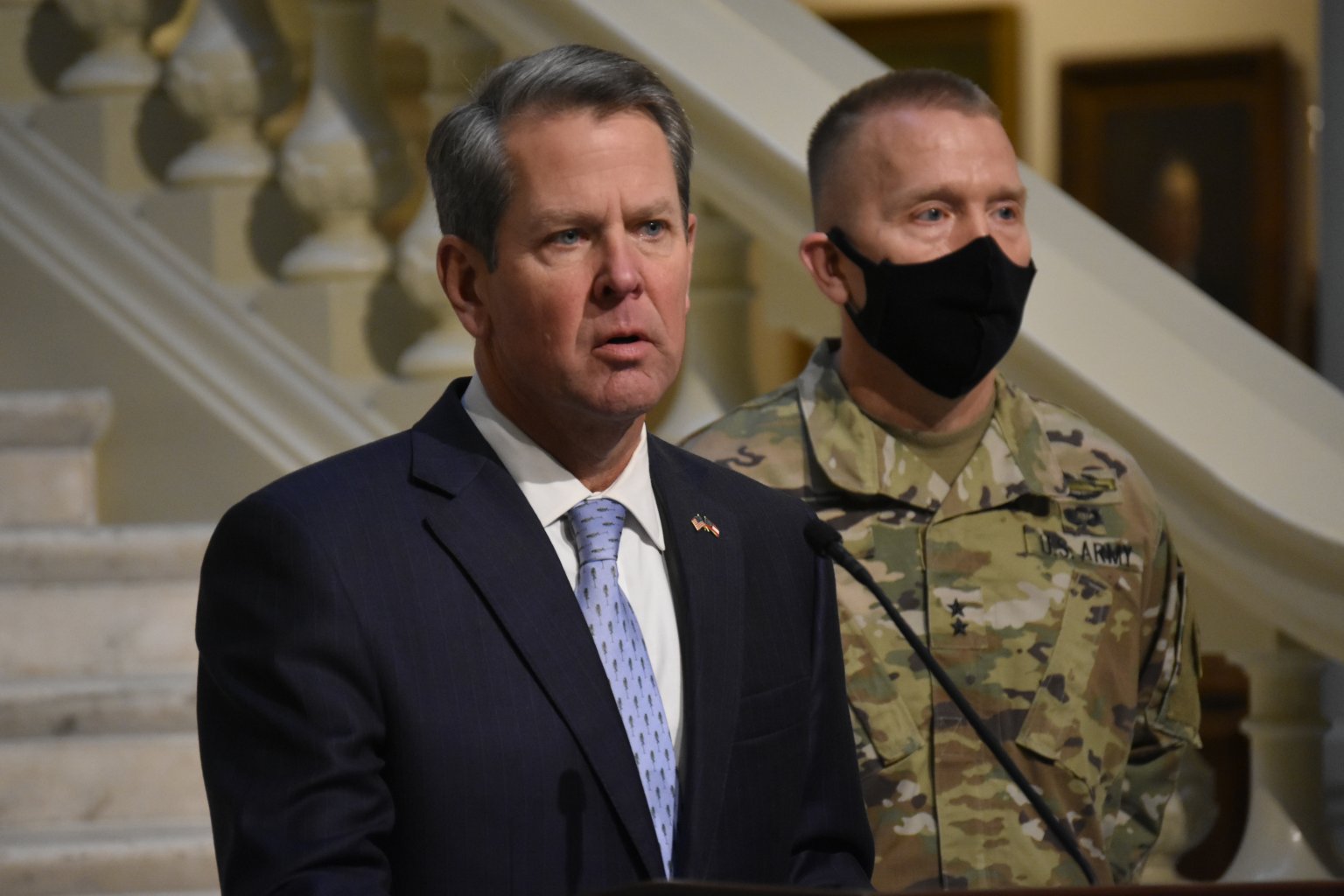

Gov. Brian Kemp urged Georgians struggling to get a COVID-19 vaccine to stay patient as the state deals with early technical glitches and supply shortages.

Some public health districts have advised people who want shots to stop calling as they are out of supplies. Other Georgians who are eligible to receive the vaccine say they cannot reach anyone when they try to schedule an appointment.

“Yes, the phone lines will be busy, yes the website will certainly crash,” Kemp said. “There’s simply vastly more Georgians that want the vaccine than can get it today. This is no doubt frustrating. I would prefer we have ample supply and we could vaccinate everyone we need to. Unfortunately, that is simply not possible.”

A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website Monday showed Georgia with an initial rate of 1,346 vaccinations of Pfizer or Moderna per 100,000 residents in the state, ranking last in the country.

On Tuesday, Georgia recorded 145 COVID deaths, more than any single day since the pandemic began. The previous deadliest day in Georgia since last spring was Aug. 11 when 129 deaths were attributed to COVID.

A new federal distribution plan proposed by the outgoing Trump administration is set to give top priority to states that quickly delivered a shot so far to eligible people who want one, putting Georgians at a disadvantage for now.

The state now receives about 120,000 doses of the vaccine each week, with about 40,000 of those going to nursing homes through pharmacies CVS Health and Walgreens as part of a federal agreement.

That leaves 80,000 doses per week to be distributed among Georgia’s eligible population of 1.3 million residents 65 and older and hundreds of thousands of health care workers.

So far, about a third of the nearly 700,000 doses shipped to Georgia have been distributed, according to the state health department.

Kemp blamed that low rate on technical incompatibility between the state’s reporting system and the CDC’s, doctors not immediately reporting administered shots and providers holding doses in reserve. Providers sitting on vaccine doses will face consequences, Kemp said, channeling one of his 2018 political campaign ads featuring a truck.

“If this issue continues, the state will take possession of those doses, and ensure that vaccinations continue,” he said. “If it takes me firing up my pickup truck and doing it myself, so be it.”

Some of the blame for Georgia’s low performance should fall on a lack of a federal strategy for distributing the vaccine, said Dr. Sarah McCool, clinical associate professor in the School of Public Health at Georgia State University.

“I know there’s a lot of frustration, and it’s certainly not accurate to place all the frustration on the Georgia Department of Public Health because there should have been a better federal strategy to begin with, in my opinion,” she said.

More than 10,000 Georgians have died from the pandemic, and nearly 650,000 cases have been confirmed in the state, according to data from the state health department Tuesday.

Of those Georgians unfortunate enough to get infected, 45,000 have been hospitalized, and some health systems have reached their capacity to treat them in recent weeks following gatherings over the holidays. The state has reopened the Georgia World Congress Center as an overflow facility for patients with nowhere else to go.

The federal government has been the sole purchaser and distributor of vaccines in the U.S., through a Trump administration task force dubbed Operation Warp Speed.

That effort has distributed more than 25 million doses to states, according to U.S. Health and Human Services officials and tracking data compiled by Bloomberg News. Of those, just 9 million vaccine doses have been administered.

Instead of a centralized national vaccine plan, the Trump administration has left it up to states to determine how to prioritize which people get vaccines and when to start vaccinating the next group. That’s resulted in a hodgepodge of approaches to getting vaccines into residents’ arms.

Countries with more centralized vaccine distribution plans have fared better than the U.S. so far, McCool said.

On Tuesday, the Trump administration directed state officials to expand the pool of people getting vaccinated for COVID-19 and announced that all available doses will be distributed to states instead of continuing to hold back a reserve of follow-up doses.

Under the policy changes outlined by HHS Secretary Alex Azar, states should begin vaccinating anyone 65 and older and those under 65 who have underlying health conditions that put them at increased risk of severe COVID-19 symptoms.

States also are urged to expand the sites being used for vaccinations. And the number of vaccine doses sent to states each week will no longer be based on population, but rather on the pace of vaccine administration and the number of residents 65 and older.

“Every vaccine dose that is sitting in a warehouse rather than going into an arm could mean one more life lost or one more hospital bed occupied,” Azar told reporters.

In two weeks, as things stand, the allocation of COVID-19 vaccines will be based on the percentage of doses each state has successfully administered thus far and the number of residents aged 65 or over. That could mean fewer vaccines for Georgians if the state’s distribution rate remains low.

Kemp suggested that allocation will likely not stand when President-elect Joe Biden takes office Jan. 20.

“Obviously, in two weeks that can change,” he said. “Quite honestly, I think that probably will with the new administration, but we’ll stand by and watch that.”

Kemp thanked Vice President Mike Pence for his work with the coronavirus task force, saying he hopes the new administration will work as closely with states as the current one.

But a new administration can only do so much to solve problems caused by a health care system fragmented between public health and private providers, McCool said.

“It really is a massive structural change that needs to occur within the health care system, ultimately, if we were to position ourselves for success, just because there’s so much lack of coordination in the health care system in general,” she said.

“In something of this magnitude, it’s much more difficult to do a course correction mid-stream,” she added. “I think we are going to have some big lessons learned from this pandemic and hopefully implement them the next time around. Hopefully there won’t be a next time around, but most likely there will be at some point. The best lesson is to have a centralized strategy in place that doesn’t kind of leave everything up to the states.”

This article appears in partnership with Georgia Recorder