State lawmakers today are set to debate revising or repealing Georgia’s citizen’s arrest law as they examine how to avoid the type of vigilantism that resulted in the killing of Ahmaud Arbery earlier this year.

Today is the first of a series of meetings this month to give legislators a chance to hear from law enforcement representatives, criminal justice reform advocates and others about the Civil War-era law that allows residents to detain someone they suspect of committing a crime if police aren’t around.

Giving police powers to an average citizen can put law enforcement, prosecutors and others in a precarious situation, said Rep. Dar’shun Kendrick, a Lithonia Democrat and member of the House committee that will take up the discussion that started near the end of the 2020 legislative session last month.

“The message is loud and clear that whatever we need to do to make sure that every citizen, but particularly African Americans who are unfairly targeted, are not going to be the victims of perpetrators who are able to be shielded by laws that are applied differently to different people,” said Kendrick, chief deputy whip for the minority caucus.

But several Republican committee members say they are taking a more nuanced approach heading into this month’s meetings.

The hearings will allow the committee to vet whether repealing the law is the best policy, said Rep. Chuck Efstration, a Dacula Republican and chair of the committee. He said he’s optimistic that the group will fashion some proposal as legislation for next year’s General Assembly to consider.

Efstration played a key role pushing through Georgia’s new hate crimes law. He sponsored the legislation Gov. Brian Kemp signed into law in June after it languished in a Senate committee for well over a year.

Like the hate crimes law, citizen’s arrest became a focal point of legislators after the March viral video of Arbery’s killing at the hands of a group of white men. Some lawmakers hoped to push through citizen’s arrest revisions as the 2020 legislative session came to a close in June, but ultimately they ran out of time.

A Waycross prosecutor cited the law as justification for the actions of the men who pursued and killed the Black 25-year-old as he ran through a neighborhood near Brunswick.

“The citizen’s arrest law is at the top of mind right now because of the Ahmaud Arbery case,” Efstration said. “The bipartisan work that we were able to bring into passing a historic hate crimes law in Georgia is an important foundation from which we can work on citizen’s arrest law and other very important issues.”

Efstration’s counterparts in the state Senate also plan to study changes to the state’s citizen’s arrest law as they consider a variety of changes to policing tactics and training, said Sen. Bill Cowsert, an Athens Republican set to lead the new committee.

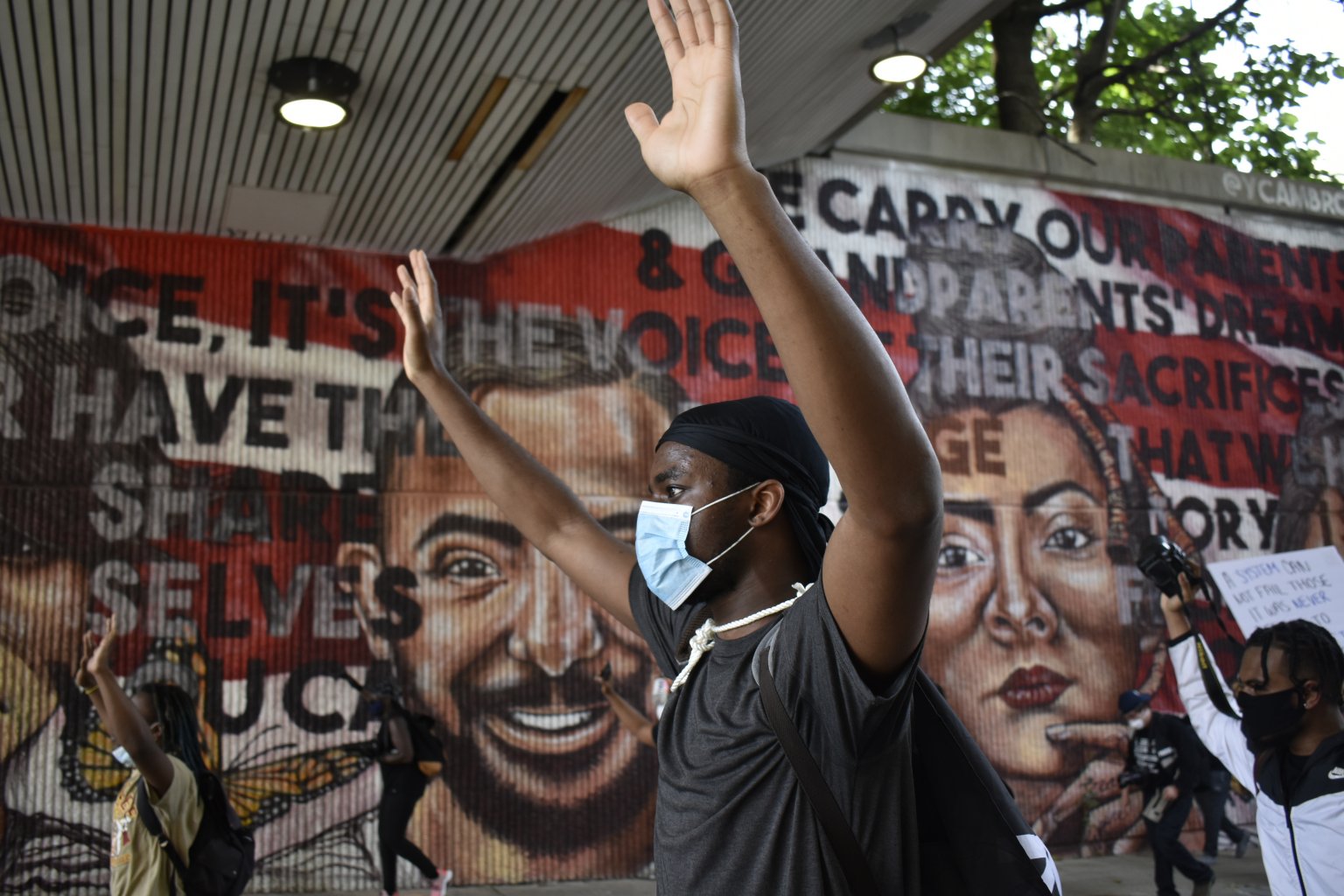

The death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police added to the outrage that followed the release of the Arbery video and large protests in June reached the steps of the state Capitol more than once. Demonstrators demanded an end to police brutality and policing reform with a visibility and volume that has caught the attention of legislators.

“We want to try to get a consensus on what is expected from law enforcement and citizens and their interactions,” Cowsert said. “That seemed to be the root of a lot of the current problems and I thought it needed some more thorough study and evaluation before we did anything rash.”

To repeal, or to clarify

A recurring criticism of Georgia’s citizen’s arrest law is it is difficult to interpret and enforce, problems found in the citizen’s arrest laws in some other states as well.

An average member of the public can detain someone under Georgia’s citizen’s arrest law if a crime is committed in their presence or “within his immediate knowledge.” And for a felony, a person can be stopped from getting away if there are “reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion.”

Travis and Greg McMichael are charged with murder in Arbery’s death and a state investigator said at a hearing for them last month that they chased him through the Satilla Shores neighborhood in a pickup truck. The father and son later claimed they suspected Arbery of neighborhood burglaries and only intended to detain him until police arrived when Travis McMichael’s shotgun went off in a struggle with the jogger.

Mercer law professor Tim Floyd said Georgia’s law is confusing and needs revising at the least.

“I think it’s a good idea to repeal the statute altogether but at a minimum it really ought to be clarified” he said. “Because it is not helpful for a private citizen trying to understand what the law authorizes.”

Some Democrats on the judiciary committee say they are in favor of repealing the law with an exception – continuing to give security guards and store owners the ability to detain someone who commits a crime in a business.

“That’s different from the citizen’s arrest statute because it’s not an arrest because No. 1, you’re not chasing someone to a location because they are already on the premises,” said Sandy Springs Democrat Rep. Josh McLaurin.

Some lawmakers say if they can’t get the citizen’s arrest law repealed, then they will support clarifying the law to lessen the likelihood that confrontations turn deadly.

Rep. William Boddie, an East Point Democrat, says that could still lead to someone overreacting.

A major reason to get rid of the law, which dates back to 1863, is because it’s steeped in racism, McLaurin said. The law empowered people to chase and capture runaway slaves during the Civil War.

“It’s why the pain resulting from Mr. Arbery’s murder in connection with this statute resonates so loudly, because it has those echoes of trying to chase and trap another human being,” McLaurin said.