Before traveling to China in late January, Holly Bik and her husband watched countless news reports and read as much as they could about the novel coronavirus, which had been detected in the country a few weeks earlier.

Bik’s husband is from China. (She prefers not to publicize his name because of the sensitive situation in his homeland, but he is on an academic fellowship at the University of Georgia.) The couple, who live in Athens, had their first baby last June and wanted the infant to meet his great-grandfather, who was recovering from surgery in a district called Qingpu, a suburb of Shanghai.

Qingpu is about 500 miles east of Wuhan, the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak. And as the family contemplated their trip, it still appeared that the virus was mostly confined to the Wuhan area.

After weighing the odds, the couple went ahead with their travel plans. Things would be fine, they figured. They weren’t going to the heart of the outbreak. “We worked with the best information that we could have at the time,” said Bik, an assistant professor of marine sciences at UGA.

But the coronavirus situation degraded rapidly even as they were flying from Atlanta to China.

“It wasn’t until we actually had gotten to China that everything blew up in the media, and . . . the scale of the problem really became apparent,” recalled Bik. As the disease spread and caused more deaths in China, the government there began taking more active measures.

Bik, her husband and their 8-month-old son soon had to scramble to find a way back to Georgia, where they then spent 14 days quarantined inside their Athens residence.

Waiting for what happens next

The Georgia Department of Public Health says that, at any one time, about 200 people are quarantining themselves in the state due to recent travel that may have exposed them to the novel coronavirus, which is now officially known as COVID-19.

On Monday, Gov. Brian Kemp said two people in Fulton County had tested positive for the virus. One, identified as a 56-year-old man, recently traveled to Milan, Italy, where there is a significant outbreak. The other is his 15-year-old son.

An outbreak of respiratory disease first detected in China in late December was traced to a new kind of coronavirus. Since then, people have tested positive for the disease in more than 70 other countries. Symptoms are similar to the flu, and people may experience fever, cough, and shortness of breath. The severity of the disease can vary widely.

Supplies the family took

There have been more than 120 confirmed cases in more than a dozen U.S. states, including Georgia, Arizona, California, Illinois, Massachusetts, Washington, and Wisconsin. Most of the people who have tested positive for coronavirus in this country were connected to overseas travel. Eleven deaths have been reported in the United States as of Wednesday, and globally the disease has been deadly in about 3 percent of those infected.

As more people test positive in a growing number of countries, public health experts are bracing for a broader impact in the United States.

“It’s not so much a question of if this will happen anymore, but rather more a question of exactly when this will happen and how many people in the country will have a severe illness,” said Dr. Nancy Messonnier, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the CDC.

The focus to date has been on containing the spread of the disease by limiting travel to affected regions, identifying and isolating people showing symptoms, and asking travelers who may have been exposed to COVID-19 to voluntarily isolate themselves, as Bik’s family did.

Americans should start developing plans for what to do if authorities take more drastic steps against the disease, like the closing of schools and canceling of public gatherings, Messonnier said in a briefing in late February.

“I understand this whole situation may seem overwhelming and that disruption to everyday life may be severe,” she said last week. “But these are things that people need to start thinking about now.”

Bik and her family have had a preview of what could happen here — although there’s no certainty that it will.

The family has a lot of experience traveling to China. Over the course of their earlier visits, Bik and her husband established a bit of a routine. They stayed at the same hotel each time and frequented their favorite restaurants.

At the time of their flight on Jan. 25, the U.S. State Department had issued its lowest travel advisory — a Level 1 — which warns travelers to “exercise normal precautions.”

At the time of their flight on Jan. 25, the U.S. State Department had issued its lowest travel advisory — a Level 1 — which warns travelers to “exercise normal precautions.”

Bik and her husband were aware that there was a certain risk, but didn’t see it as that serious. To prepare for their flight, the couple purchased respirator face masks and Motrin for their baby, which they tweeted about on Jan. 24.

But when they arrived in Shanghai, the bustling metropolis they were familiar with had visibly changed. “Everyone was just staying indoors,” Bik said.

Government officials had suspended long-distance bus service in and out of the city. Businesses that didn’t provide utilities, food, and medical supplies or services had been closed.

“It felt like you’re walking around early on a Sunday morning when everyone’s in bed and nothing’s really happening. It’s kind of just very quiet,” Bik recalled.

The retirement home where their elderly relative was staying had stopped visitations in order to protect residents, but they got special permission to visit him twice, for about an hour and a half each time, Bik said.

From there, things started happening quickly.

On Jan. 30, the World Health Organization issued a statement declaring the coronavirus outbreak a “public health emergency of international concern.”

On Jan. 31, Delta Air Lines, the main air carrier out of Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson Airport, announced that it would be suspending flights to and from China until April. Other major airlines, like United, American Airlines and British Airways announced similar plans.

On Jan. 31, Delta Air Lines, the main air carrier out of Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson Airport, announced that it would be suspending flights to and from China until April. Other major airlines, like United, American Airlines and British Airways announced similar plans.

The hotel in Shanghai where the family was staying began to simplify the menu — rationing food because the hotel manager was unsure how long supplies would last during the lockdown. All individuals who left the building had to have their temperature checked by the doorman before they were allowed back in.

By Feb. 2, the U.S. State Department had elevated its travel warning for China from the lowest level to the highest: “Do not travel.”

“It just didn’t seem like there was any end in sight to when they were going to go back to normal,” Bik said. Her family found themselves “scrambling to get home.”

From high anxiety to cabin fever

Fortunately for Bik, her family had rescheduled their return flight before Delta announced flight cancellations. But getting home now meant first flying to Japan, and undergoing more rounds of temperature checks and evaluations.

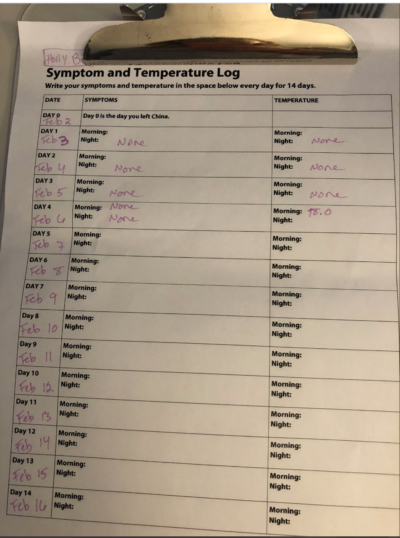

When they went through customs after finally landing in Atlanta, they were pulled aside and questioned about where in China they had traveled. No one in the family had a fever or other symptoms, but it was recommended that they self-quarantine for 14 days, avoid crowded places and stay about 6 feet away from other people.

This is the recommended procedure because the incubation period of the virus — the time between a person catching it and showing symptoms — can be up to 14 days. A person who is infected can have few or no symptoms but still potentially infect others during that time, health officials warn.

For people who have been to China or have been “exposed to someone sick with COVID-19 in the last 14 days,” the CDC recommends limitations on normal activities. In other words, a self-quarantine.

Bik and family didn’t mind quarantining themselves, at least not at first. They had been through an ordeal in China, and when they got back to Georgia they were exhausted and experiencing jet lag. “We could take naps and just slowly get our bodies readjusted to the time zone,” she said.

There was even an intellectual dimension to the situation. “The scientist in me is enjoying being part of an epidemiological study,” Bik tweeted on Feb 7.

Bik stayed on top of her job by working from home, using e-mail and video calls to stand in for face-to-face meetings. Her husband did the same.

So the quarantine period was bearable, but Bik suggests that it got old fairly fast.

When asked to describe the realities of being grounded for two weeks, she said it wasn’t easy being stuck at home. She wanted to get out and do ordinary things again.

“It was more frustrating than anything, knowing that you can’t leave. Like I can’t go to a coffee shop or I can’t go to yoga,” she said.

Still, she’s glad she and her family heeded the recommendation of health authorities and self-quarantined. It was the sensible thing to do.

After 14 days, they still had no symptoms.

“Better be safe than sorry for this type of thing,” Bik said.

The Biks are back at work. But the situation continues to evolve.

UGA on Monday announced plans to suspend travel programs that take students to Italy, South Korea and China for the Spring 2020 term. Students returning from those three countries — all of which have experienced COVID-19 outbreaks — are asked to self-quarantine for 14 days.

GETTING PREPARED

There are currently no medications and no vaccines available to protect against COVID-19, so the CDC recommends preventative measures, such as:

- Staying home when you’re sick

- Covering coughs and sneezes with a tissue (and then washing your hands)

- Cleaning objects and surfaces you touch often

- Washing your hands frequently (especially after going to the bathroom, before eating and after you cough, sneeze or blow your nose)

Madeline Laguaite is a freelance journalist and a health and medical journalism graduate student at the University of Georgia. She is particularly interested in LGBTQ health and public health. She has a public/professional Twitter at @MLaguaite and a portfolio at madelinelaguaite.com.

Andi Clements is a public relations graduate student at the University of Georgia. She received her bachelor’s degree in economics and is interested in business and non-profit sustainability. She has a portfolio at https://andiclements.wixsite.com/mysite

Brittany Carter is a journalism graduate student at the University of Georgia. She is interested in environmental sustainability and mental health. She has a professional portfolio athttp://brittanynicole.net.

Jillian Tracy is a journalism student at the University of Georgia. She is interested in the intersection of issues, including politics, media and health. She has a public/professional Twitter at @JillianNTracy and a portfolio at https://jilliantracy24.wixsite.com/profile.