The following is an excerpt from the book “Love & Duty” written by Col. Ben & Anne Purcell (1992, St. Martin’s Press). Purcell was aboard a helicopter that crashed in a cemetery near Quang Tri City on Feb. 8, 1968. Five others were also on board, including Pvt. James E. George, Jr. of Fort Worth, Texas. George was severely burned when he returned to the downed aircraft to retrieve his weapon. What follows is Col. Purcell’s account of the young soldier’s final moments.

The VC took the shoelaces from the boots and used them to tie our thumbs together behind our backs. They tied our arms together with a rope above the elbows.

“Move,” Armband said, poking me in the ribs with the muzzle of his AK-47. He must’ve hit one of the broken ribs because there was a sudden, excruciating stab of pain, and I gasped aloud from it. Slowly we started to walk toward the small hamlet nearby. As soon as we entered the hamlet we were ordered to “face the wall.” This command alarmed us all, for only a few days before we had read about five Marines who had been found shot to death with their hands tied behind their backs. With as much conviction as I could muster, I told the others that we’re more valuable to the VC alive than dead. As it turned out, the VC only wanted to keep us from seeing the Vietnamese living in the hamlet while we paused there for a few minutes.

We started walking again. We walked more quickly now across a muddy rice paddy to a nearby canal, where we were loaded onto two sampans. I was placed in one sampan with George, while Rose, Chenoweth, and Lenker were directed to get into the other. There was a very unsettling quietness all around us; nothing was moving. Then George asked, “Colonel, are you a Christian?”

“Yes, son, I am.”

“Could you maybe say a prayer with me?”

“I would very much like to pray with you,” I answered.

There on that boat, with the smell of fish, jungle, and charcoal braziers filling our nostrils, that terribly burned young soldier and I prayed. We asked for courage and strength to face the unknown future. Prayer has always meant a lot to me, but at that particular moment it became the glue that was holding the broken pieces of my life together.

After a brief trip down the canal we got out of the sampans near another hamlet and were paraded down the street for the inhabitants to see. We walked on through the hamlet and then along a small narrow path that led toward the mountains in the distance. We walked all night long and by the next morning our feet were raw with cuts, bruises, and broken blisters.

George was still suffering terribly and I honestly don’t know how he lasted this long. By now he could no longer see to walk because his badly burned face had swollen to the degree that his eyes were shut. By the time we reached the mountains George had reached his limit. But other than a few quiet, almost apologetic moans of pain, he said nothing. He tried to stay with us, but he began stumbling around, falling every two or three steps.

“You go!” Armband said to him. “You make everyone slow!”

George tried to get up but he fell again.

“You go!”

“Can’t you see how badly wounded he is?” I asked. “You must get medical attention for this man immediately.”

“Quiet! You be quiet!” one of the VC replied. He pointed his AK-47 at me.

I was tired, dispirited, in pain, and still shamed over having surrendered. If he was going to shoot, let him shoot. I stared at Armband.

“I want a doctor for this man,” I said again.

“You be quiet. You not in charge. I am in charge,” Armband said. “If you speak again I will have you shot.”

This was it, the first real challenge since we were captured. It was a good time to meet the challenge, too. I was about at my limits.

“If you’re going to shoot, do it!” I challenged. “But I want a doctor for this man. Bac si, do you understand? Bac si, bac si,” I said, using the Vietnamese word for doctor.

For a long moment it was a contest of will between the VC who was holding the rifle and me. Finally Armband gave a small nod to the guard and the VC lowered his gun. I realized that I wasn’t about to be killed…at least not now.

“Yes, yes, bac si,” he answered. He said something in Vietnamese, and two VC moved George to the side of the trail and sat him down, rather gently I thought, in comparison with the way we had been treated since our capture. I felt a sense of relief. At least one of my men would find some peace.

I walked over to Private George and looked down at him. I wanted to put my hand on his shoulder, to comfort him in some way, but my hands were still tied behind my back. George wasn’t that much older than my son David, and I wished with all my heart I could do something to ease his suffering.

“James,” I said. “Or do they call you Jimmy?”

“Some call me James, some call me Jimmy,” he answered in a quiet, frightened voice.

“James, you’re going to stay here until a doctor comes.”

“Colonel, would you…would you say the Lord’s Prayer with me?”

I got on my knees beside him and we started to pray.

“No!” Armband shouted at me. “No, you can not do that! You go! You go now!”

I didn’t move. Together, James George and I repeated the Lord’s Prayer, and never in the most magnificent cathedral or the smallest chapel have the words meant more to me than they did then.

“You go!” Armband said again. I heard the metallic sound of a bolt being slammed home and I knew that Armband had cocked his weapon. I felt the barrel on the back of my neck, but I didn’t move. I continued to say the Lord’s Prayer aloud with James.

Armband let out a bellow of rage and turned away, jerking the gun away with him. I wondered why he was so angry, why he was so against allowing George this comfort. Then, with an insight that was born of that travail, I realized what it was. He was frightened. He was frightened at coming face to face with a faith that was stronger than fear.

“Thank you, Colonel,” George said when the prayer was finished. “I’ll be all right now. Whatever happens, it’ll be all right.”

“Okay! Go! You go now!” Armband shouted, lifting me back to my feet and shoving me with the barrel of the gun. I joined the others and we were herded up the trail. I looked around once and saw one of the VC standing behind George. The VC guard nearest me clubbed me right between the shoulders, forcing me to look back to the front. After we had moved out of sight of George, we heard a shot. Startled, I looked around, but I could no longer see George.

“What was that?” I asked. “What was that shot?”

“Someone shoot, it means nothing,” Armband said.

“I want to go back.”

“No.”

“Did you shoot Private George?”

Armband looked at me for a moment; then he shook his head…

Epilogue

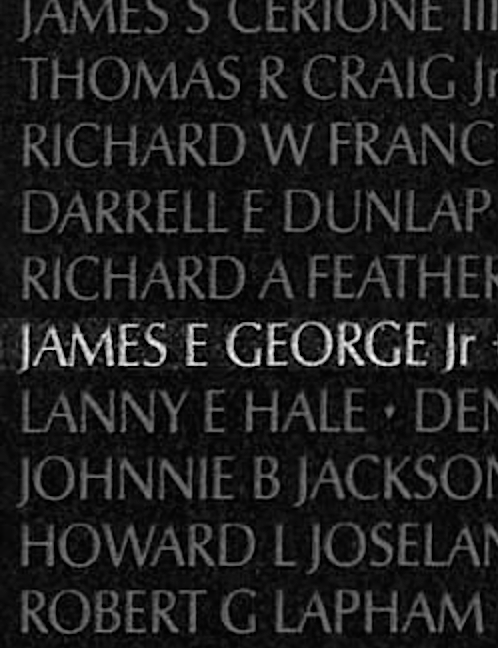

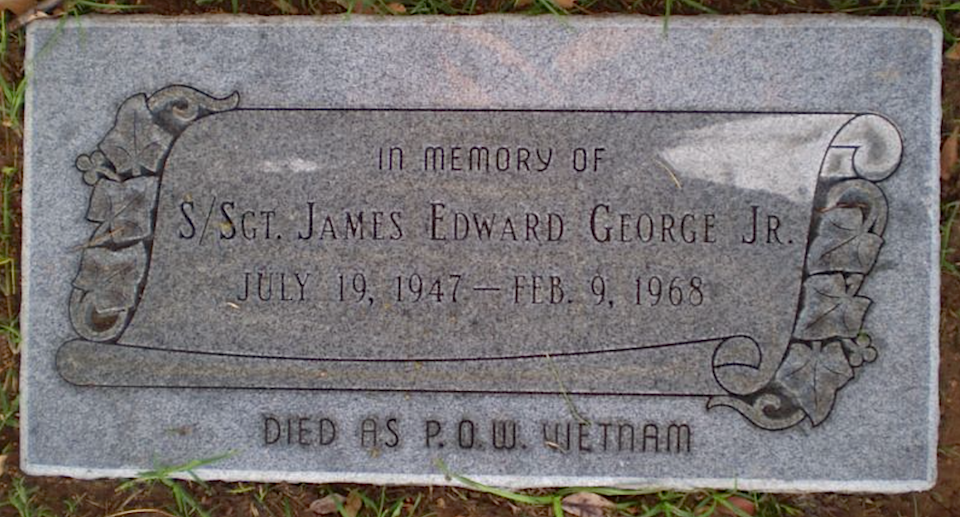

The Army promoted James George Jr. after he was captured. He was not among the 566 U.S. military POWs who returned home at the end of the war. His name appears on panel 38E, line 28 of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington DC. SSGT George also is memorialized on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Hawaii.

James George was 20 years old when he died. He was the only child of James Edward and Avo Clements George of Fort Worth, Texas. When Ben Purcell returned home from the war in 1973, he and his wife, Anne, traveled to Texas to visit the couple. Purcell shared with them what he knew of their son’s final moments.

Col. Purcell carried the young soldier’s memory with him until his dying day.

In Laurel Land Memorial Park cemetery in Fort Worth, there is a marker with SSGT James George’s name on it. It rests near the graves of his parents.

This article first appeared on Now Habersham on Memorial Day, May 28, 2018.