The Pew Charitable Trusts recently launched a project aimed at reducing suicide rates by making risk assessment a part of routine hospital visits.

Evidence-based screening tools exist that can help health care providers quickly and easily identify patients at risk for suicide, but they’re not widely used, said Kristen Mizzi Angelone, a senior manager with the Trusts’ Suicide Risk Reduction Project.

Suicide is preventable, Angelone said, and universal assessment of suicide risk would save lives.

“We’re really focusing on the health care system right now because statistics show that about half of people who die by suicide have interacted with the health care system within a month of their deaths,” Angelone said. “So we know that this is a crucial intervention point to identify people who may be at risk of suicide.”

Suicide is not a new concern, but the coronavirus pandemic is exacerbating all mental health and substance use disorders.

A record number of people overdosed and died nationwide in the 12-month period ending in January 2021, according the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, including more than 1,900 Georgians. That is a 38.8% increase over state data from the previous year, which was higher than the national average of about 31%.

The numbers are likely underreported.

When Georgia released its first revenue report after the pandemic took hold, tax collections from alcohol sales had risen 13%.

The Georgia Council on Substance Abuse said people in isolation due to the pandemic are more likely to experiment with addictive substances for the first time, and that people in recovery are at risk of relapsing when forced to avoid social activities. That includes in-person recovery meetings.

MORE: This Is What Happens When Georgians Experience Mental Health Or Addiction Crisis

The opposite of addiction is connection, said Jeff Breedlove, the Council’s spokesman.

“It’s happening already and it’s only going to get worse before it gets better,” he said of the problem.

Suicide is an urgent public health issue across the United States, affecting people across urban areas, rural areas, and all racial and ethnic groups, Angelone said.

Rates of suicide have increased dramatically over the last 20 years, especially among veterans and people who identify as LGBTQ.

RELATED: A suicide epidemic is killing Georgia’s first responders. Help from lawmakers is slow in coming

Suicide was the 12th leading cause of death in 2020, the CDC reported.

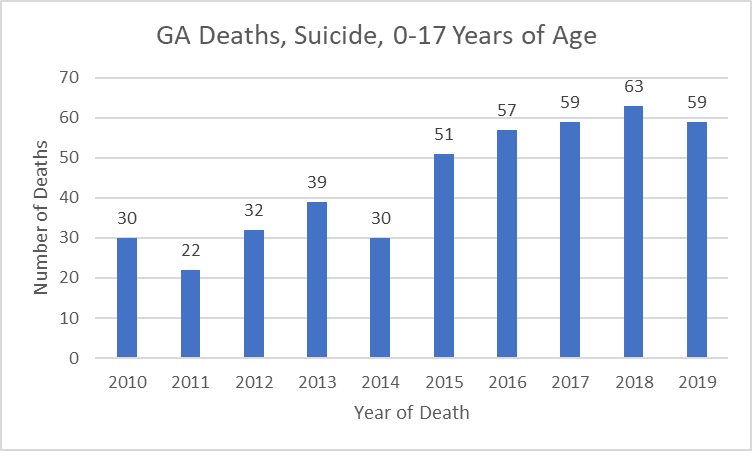

For Georgians between ages 10 and 17, the rate of completed suicides has been 1.8 times higher during the past five years compared to the prior five-year period.

Over the next two years, the Suicide Risk Reduction Project plans to work closely with a cohort of hospitals, helping them implement changes and overcome obstacles to risk assessment implementation, Angelone said.

They are hoping to bring together about 10 to 12 rural, urban, large and small hospitals that serve a diversity of patients, and work with the administrations to implement an expanded set of suicide care practices.

“At the end of this, we hope to publish the findings of a case study of this experience as an example for other hospitals around the country that are interested in expanding what they’re doing around suicide,” Angelone said.

Experts have not yet established a baseline of what suicide care in the United States currently looks like, such as exactly how many hospitals have expanded their suicide screening practices or what those suicide care practices look like across the country.

Angelone said researchers with the Suicide Risk Reduction Project will conduct a survey this year, hoping to publish findings early in 2023.

The hope is that the cohort of hospitals can serve as a model for hospitals and health systems around the country.

“There is a lot that hospitals and health systems can do to identify these folks [at risk of suicide] and provide them with the care they need,” Angelone said. “We’re really looking forward to seeing how the next two years go.”

MORE: 988 will be the ‘911’ for mental health/addiction crisis calls. Georgia preps for the extra load

This summer, Georgia will join the nation in using a single three-digit crisis hotline: 988 is meant to be the “911” of behavioral health, said Judy Fitzgerald, the commissioner of the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities.

Establishing 988 for suicide prevention and mental health crisis services will make it easier for Georgians in crisis to access the help they need and decrease the stigma surrounding suicide and mental health.

The 988 emergency line goes live July 16.

“This is probably one of the largest and most transformative initiatives that I’m going to experience in my lifetime in behavioral health,” Fitzgerald said.

If you or someone you love is experiencing a mental health emergency, call Georgia’s current Crisis Access Line at 1-800-715-4225.

This article appears on Now Habersham through a news partnership with GPB News